Article via Global News | By Leslie Young | February 16, 2016

Last Thursday morning, in a small town outside Ottawa, a man shot a woman.

The two had been partners, according to media reports, but weren’t anymore. The woman, Sarah Cameron, was at her parents’ house in Almonte. She was seriously injured in the attack, but not killed. Her father, Mississippi Mills town councillor Bernard Cameron, who was also home at the time, was.

Sarah is hardly alone. In 2014, there were 70 attempted murders of women by their current or former intimate partners, according to Statistics Canada. Another 70 women were killed by intimate partners.

That’s one woman killed by her partner roughly every five days.

And in some ways, women in small towns or rural areas are in even more danger than their urban counterparts.

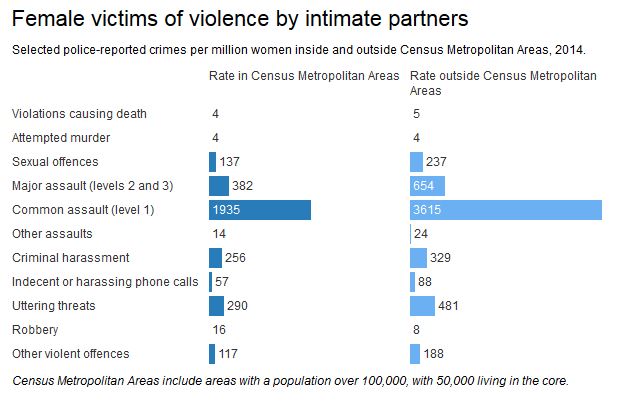

While the rate of offences causing death is only slightly higher in rural areas — five out of every 1 million women in rural areas or small towns vs. four in urban ones — rural women are much more likely to experience other crimes, such as assaults, at the hands of their current or former intimate partner.

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics. Get the data

It comes down to isolation, say women’s advocates.

To start with, if a situation becomes a crisis, the police can’t immediately help. “Police aren’t nearby,” said Jo-Anne Dusel, provincial coordinator for the Provincial Association of Transition Houses and Services of Saskatchewan.

“If you’re in a dangerous situation, violence is imminent and you want to call for help, you know perfectly well it’s going to be half an hour, an hour before someone gets to you. Plenty could happen in that time.”

If there are no neighbours nearby, others aren’t able to intervene or call for help. And without public transportation, it can be physically difficult to leave an abusive household if the abusive partner controls the only car.

Close communities

Rural women may stay longer in an abusive relationship because circumstances can make it more difficult for them to leave — which could partly account for the higher rate of police-reported abuse, thinks Dusel.

Even before things get to the point of a violent emergency, there are issues getting help in rural areas, according to JoAnne Brooks, director of the Women’s Sexual Assault Centre of Renfrew County, outside Ottawa.

Living in a community where everyone knows everyone else can be comforting in some ways, but it can make reporting abuse more difficult, she said.

“Most people know everyone else or they’re related to everyone else. Or they’re related somehow to the abuser.”

“If she seeks support, say from a hospital, it’s very possible that the emergency room nurse is the perpetrator’s mother.”

And there are fewer supports available in rural areas in general. There’s only one shelter in Renfrew County, said Brooks, in an area covering 7400 square kilometres. Her own organization only has three full-time staff and mostly relies on volunteers to support women who have been sexually assaulted.

Home life

People in rural areas are more likely to have guns, said Brooks — for hunting, predator control and other such reasons. But, those weapons can be used as threats.

“Even if it’s not physically used, the gun cabinet is there, the key is in his hand, he talks about how he can open the gun cabinet at any moment. And women are very threatened by weapons,” she said.

Economic factors can also keep women at home.

People’s economic livelihood is often tied to a piece of farmland, often worth a lot of money, said Dusel. “You don’t just sell that and separate it.”

The possibility of losing the family farm can up the stakes, she said. “There are instances where that’s enough to drive the partner to violence, like to the point of homicide, when they’re faced with losing their family farm and that’s something they’re not willing to do.”

Women are also often reluctant to leave behind their pets or livestock, she said, particularly if they have ever been threatened.

Tough decisions

It all adds up to a difficult calculation on the woman’s part.

“Sometimes you have to make the choice that’s the least bad out of a bunch of choices,” said Dusel.

Brooks thinks that the lack of services, jobs and even public transportation makes leaving an abusive relationship particularly hard for rural women.

People wonder why women stay, but given that there are no resources, how can they leave, she asks. Running away means leaving everything behind, so it’s an incredibly tough decision.“It’s not fair. Why do women and children have to do that, uproot their whole lives? But the risk is that if they don’t, they can be dead, and they will have lost their lives. So. It’s a catch-terrible-22.”

Global News will be looking into the issue of rural domestic violence all this week: asking why legal protections seem inadequate, and what can be done to better protect women.

Click here to learn more about the CDHPIVP Rural, Remote, & Northern Populations Research Hub