Culturally-Informed Risk and Safety Strategies

Domestic Homicide Brief 4 | February 2018

Acknowledgements

The Domestic Homicide in Immigrant and Refugee Populations: Culturally-Informed Risk and Safety Strategies Brief is the fourth in the series developed by the Canadian Domestic Homicide Prevention Initiative with Vulnerable Populations (CDHPIVP). The Brief highlights risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning for immigrant and refugee populations. The Brief provides definitions of key terms and identifies unique risk factors for domestic homicide, using the Immigrant Power and Control Wheel. Barriers to services for immigrant and refugee women are addressed, along with the need for culturally-informed strategies for risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning. Examples of culturally-specific risk assessment tools are provided.

Suggested Citation:

Rossiter, KR., Yercich, S., Baobaid, M., Al Jamal, A., David, R., Fairbairn, J., Dawson, M., & Jaffe, P. (2018). Domestic Homicide in Immigrant and Refugee Populations: Culturally-Informed Risk and Safety Strategies (4). London, ON: Canadian Domestic Homicide Prevention Initiative. ISBN: 978-1-988412-13-9

Please evaluate!

Let us know what you think of the Domestic Homicide in Immigrant and Refugee Populations: Culturally-Informed Risk and Safety Strategies Brief by completing this brief survey: https://uwo.eu.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_8002soNG2E6sJwN

Download copies of this brief at:

http://cdhpi.ca/knowledge-mobilization

THE CDHPIVIP TEAM

| Co-Directors | |

|

|

|

|

Myrna Dawson |

Peter Jaffe |

Management Team

Marcie Campbell, Research Associate

Jordan Fairbairn, Postdoctoral Fellow

Anna-Lee Straatman, Project Manager

Graphic Design

Elsa Barreto, Multi-media Specialist

This research was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Introduction

There is limited existing research examining the prevalence of domestic violence among immigrant and refugee populations. Research reveals that rates of domestic violence within immigrant and refugee populations are not higher than other populations; however, immigrant and refugee women experiencing domestic violence face numerous barriers to disclosing and reporting violence and abuse, accessing support services, and navigating intersecting legal processes and social support systems.1,2 Understanding and preventing domestic violence and homicide within immigrant and refugee populations requires a culturally-informed lens that accounts for intersecting forms of oppression and recognizes the heterogeneity of immigrant and refugee populations.3 To be effective, risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning strategies should be culturally-informed and, where possible, culturally-specific.4

Definitions

Definitions

According to the International Organization for Migration, immigration is a process by which people move to a new country for settlement purposes.5

A migrant is defined as “any person who is moving or has moved across an international border or within a State away from his/her habitual place of residence, regardless of (1) the person’s legal status; (2) whether the movement is voluntary or involuntary; (3) what the causes for the movement are; or (4) what the length of stay is.”5 In Canada, an immigrant can be defined as a person who is residing in Canada but who was born outside the country. Immigrant populations may be further categorized as ‘recent’ immigrants (e.g., 0-10 years in host country) and non-recent immigrants (e.g., 10+ years in host country), with recent immigrants commonly referred to as ‘newcomers.’168

Refugees are individuals who migrate involuntarily or by force for a variety of reasons, including war, political or religious persecution, or natural disasters.6

Protected persons are persons determined to be Convention Refugees (as defined by the United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, signed in Geneva in 1951, and the 1967 Protocol to that Convention) or persons in need of protection. For example, persons who face risk to life, risk of cruel and unusual treatment or punishment, or danger of torture as defined in the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment.

Permanent residents are people who arrived in Canada as immigrants or refugees and who have been granted the right to live in Canada permanently.

People without status (also referred to as non-status or undocumented migrants) are individuals who are living in Canada without legal status. For example, they may have entered Canada legally but stayed beyond the expiry of a work or study permit, or they may have applied for refugee status and been denied.

Immigrant and refugee populations are referred to in a number of ways in the domestic violence literature, including as people of immigrant descent, undocumented immigrants, foreign-born individuals, foreign nationals, non-citizen immigrants, minority groups, and visible minorities; however, not all people of immigrant descent, minority groups, or visible minorities are immigrants or refugees.

In this Brief, the term culturally-informed is used to refer to risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning strategies that are informed by, and reflective of, different cultural perspectives of domestic violence and homicide, while the term culturally-specific is used to refer to risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning strategies and tools that have been developed for use with specific cultural groups.

Domestic Violence and Homicide in Immigrant and Refugee Populations

Immigrants and refugees are a heterogeneous population with a wide range of cultural, ethnic, and religious backgrounds and pre- and post-migration experiences.7 Understanding, preventing, and responding to domestic violence within immigrant and refugee populations therefore requires a multifaceted and culturally-informed approach that addresses well established risk factors and safety needs, as well as considerations that reflect the unique circumstances and cultural contexts of specific groups.8,9

Researchers have identified several factors that contribute to increased vulnerability and risk of domestic violence and homicide among immigrant and refugee populations.10-45

These include:

These include:

- Acculturation level

- Cultural norms and expectations

- Geographic and social isolation

- Length of residency in host country

- Loss of socioeconomic status

- Loss of culture, family structures, and community leaders

- Power imbalances between partners

- Stress associated with migration

- Post-migration strain and stigma

- Strict or changing gender roles

- Traditional patriarchal beliefs

- Unresolved pre-migration trauma

- Victim/survivor immigration status

Post-migration stressors can have an impact on family dynamics and create the conditions for domestic violence within immigrant and refugee populations.27 The integration process is impacted by many factors, including social isolation and exclusion, limited English or French language proficiency, and limited access to resources.46 Immigrant and refugee women and their families may experience a variety of unique challenges linked to pre-migration trauma, immigration status, loss of social support networks, neighbourhood factors, and socio-economic hardships that can negatively impact the family’s well-being, heighten conflict post-migration,47 and increase the risk for domestic violence.27,31,48

Length of residency has been recognized as a risk factor for domestic violence among immigrant and refugee populations, with risk increasing for immigrant women who have resided in their host country for longer periods of time.7,12,38 Research suggests that recent immigrants experience lower rates of intimate partner violence than Canadian-born women.49-51 Research has also found that recent immigrants are more likely than non-recent immigrants to report to police but less likely to access support services, and that they are generally less likely to report domestic violence than Canadian-born women.52,53 Low reporting rates for recent immigrants may be a reflection of limitations in research methodologies, fear of legal consequences, linguistic barriers, or drawing negative attention to themselves and/or their community.

Country of origin is also relevant, with research suggesting that immigrant women from non-western and developing countries are at an increased risk of violence compared to immigrant women from western and developed countries.12,38,50,51 Women without status, or undocumented migrants, also face greater risk of domestic violence and barriers to support services and protection.54-63

Conceptualizing Domestic Violence

While conceptualizations of domestic violence may be common across cultural groups, unique definitions and dynamics are sometimes observed across cultures. For example, if we shift away from an individualist perspective, we can see that domestic violence may not be limited to intimate partners, male intimate partners may not be the primary or sole perpetrators, and incidents of domestic violence or homicide may involve multiple perpetrators and victims/survivors, including extended family members.

It is important to recognize that domestic violence and homicide among immigrant and refugee populations are not rooted specific in cultures, but in patriarchy. Other forms of violence against women that are often discussed in relation to domestic violence among immigrant and refugee populations include so-called ‘honour-based’ crimes, dowry-related crimes, and early, child, and forced marriages.64,65 Yet, these forms of violence are not experienced by any one culture, and may be experienced by other vulnerable populations (e.g., forced marriages also impact people with disabilities and LGBTQ communities). As such, these forms of violence, while relevant to discussions of domestic violence, must be seen as forms of gender-based violence rooted in patriarchy, and not as issues associated with any one culture or religion.42,66

It is important to consider cultural differences in risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning for domestic violence and homicide. For example, domestic violence may remain hidden in collectivist cultures, where concepts of family unity, honour, and shame have been found to be important.18,23,25,34,67-71 Shifting our understanding of domestic violence and homicide (e.g., from an individualistic to a collectivist perspective) can assist us in improving risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning strategies within immigrant and refugee populations. Identifying intersecting forms of oppression can also help us to better understand the unique factors and dynamics at play that contribute to vulnerability and barriers to support for immigrant and refugee women experiencing domestic violence.28,72

So-called ‘Honour-based Violence’

There remains significant debate about how so-called ‘honour-based violence’ and ‘honour killings’ are conceptualized in Canada.66,73-76 Addressing honour-based violence requires increasing awareness in communities and among service providers, culturally-specific risk assessment and management strategies, and an emphasis on family harmony in place of violence and coercion.77,78 Recommendations from the United Kingdom point to greater collaboration between law enforcement and anti-violence services, and ongoing support and safety planning for women who are not able to leave violent situations.79

There remains significant debate about how so-called ‘honour-based violence’ and ‘honour killings’ are conceptualized in Canada.66,73-76 Addressing honour-based violence requires increasing awareness in communities and among service providers, culturally-specific risk assessment and management strategies, and an emphasis on family harmony in place of violence and coercion.77,78 Recommendations from the United Kingdom point to greater collaboration between law enforcement and anti-violence services, and ongoing support and safety planning for women who are not able to leave violent situations.79

Power and Control in Immigrant and Refugee Populations

Research points to a number of unique power and control tactics within immigrant and refugee populations.15 The Immigrant Power & Control Wheel was developed by the National Center on Domestic and Sexual Violence, and adapted from the original Power & Control Wheel developed by the Domestic Abuse Intervention Programs (DAIP). It highlights some of the unique ways in which power and control are exerted against immigrant and refugee women.

The Muslim Power and Control Wheel,80 developed by Dr. Sharifa Alkhateeb, is another adaptation of the traditional Power and Control Wheel. This culturally-informed wheel illustrates how religious beliefs can be used to justify domestic violence, and demonstrates how control tactics identified in the original wheel can manifest in unique ways within the family context for some Muslim families.

Risk Assessment with Immigrant and Refugee Populations

Research has identified several risk factors for increased likelihood and severity of future domestic violence, including domestic homicide. These include relationship problems (e.g., restraining order, recent or pending separation), past violent behaviour, perpetrator mental illness, and suicidal or homicidal ideation.81 Within immigrant and refugee populations, research suggests that migration history and cultural differences may increase the risk of domestic violence;35 however, there is little research to suggest that these same factors increase the risk of domestic homicide.

Research on the unique risk factors for repeated, escalating, and potentially lethal violence within immigrant and refugee populations points to migration processes, immigration status, length of residency in host country, acculturation levels, gender role expectations, socioeconomic status, marginalization, and social isolation.36,76,82 Community and cultural norms (e.g., collectivist values, family privacy, stigma surrounding divorce, social acceptance of violence) may also influence awareness of, and assessment of risk for, domestic violence and homicide,19,83-86 while culture conflict and racism add to stressors experienced by immigrant and refugee populations.13,85 Patriarchal and cultural beliefs (e.g., honour, control of sexuality) also contribute to risk by decreasing the likelihood that survivors will seek formal domestic violence supports.10,83,85

As outlined in the Domestic Homicide Brief 2, Domestic Violence Risk Assessment: Informing Safety Planning & Risk Management,81 there are several commonly used domestic violence risk assessment tools. Most of these tools have been designed to assess risk for domestic violence within Western contexts. As such, they may not adequately account for the unique risk factors and cultural contexts of immigrant and refugee populations.

Assessing risk with immigrant and refugee populations requires a culturally-sensitive approach that considers specific cultural contexts while avoiding stereotyping groups.46,66 Given the heterogeneity of immigrant and refugee populations, it is important to have culturally-validated risk assessment tools.42 Researchers continue to call for the development of more culturally-appropriate and holistic risk assessment tools,31,58,77,85 and domestic violence risk assessment tools are increasingly being developed or adapted for immigrant and refugee populations.81 Table 1 highlights several tools that attempt to capture unique risk factors for immigrant and refugee populations. These risk assessment instruments account for culturally-specific aspects of risk, and can be used in conjunction with commonly used standardized domestic violence risk assessment tools that have been validated through research.

Researchers also suggest that domestic violence risk assessment should be conducted in collaboration with others, including religious leaders, healthcare workers, and other social service providers.3,87 If risk assessments are conducted in English, trained interpreters should also be involved in the process, as needed.2

Table 1. Culturally-Specific Domestic Violence Risk Assessment Tools

|

Chinese Risk Assessment Tool for Victims (CRAT-V) and Perpetrators (CRAT-P) |

The CRAT-V is an actuarial risk assessment instrument developed to predict risk of future domestic violence victimization in Chinese populations. This tool assesses 5 culture-specific risk factors, such as in-law conflict and relationship distress, as well as population-specific variables that impact disclosure and/or reporting of domestic violence. The CRAT-P is a similar tool used to assess unique risk factors for domestic violence among Chinese perpetrators. It accounts for the impact on domestic violence of unique cultural values and experiences such as “losing face.”88,89 |

|

Danger Assessment for Immigrant Women (DA-I) |

The DA-I is a culturally-competent risk assessment instrument adapted from the original Danger Assessment (DA). It aims to predict domestic violence recidivism (re-assault) and severe domestic violence among immigrant women, and has been found to have higher predictive validity for immigrant women than the original DA.90 The DA-I includes 15 risk factors from the original DA and 11 culturally-specific risk factors, such as ‘language of interview is English,’ ‘he prevents you from going to school, getting job training, and so forth,’ and ‘threatened to report you.’ It is a useful tool for safety planning with immigrant and refugee women experiencing domestic violence.91 |

|

Domestic Abuse, Stalking and Honour Based Violence (DASH) |

The DASH is a risk identification, assessment and management model for domestic abuse, stalking and harassment, and honour-based violence. The tool is used by police services in the UK and is aligned with the RARA model of risk management (Remove the risk, Avoid the risk, Reduce the risk, and Accept the risk).92 |

|

Four Aspects Screening Tool (FAST) |

The FAST is a domestic violence screening and assessment tool developed for use with minority, newcomer, and immigrant groups, and within collectivist cultures. The tool focuses on four primary and potentially intersecting aspects that operate as sources of risk within families: (1) universal; (2) ethno-cultural; (3) migration experience; and (4) religious faith.93 |

|

PATRIARCH |

The PATRIARCH is a checklist of 15 risk and vulnerability factors for patriarchal violence where honour is a motive. The tool is based on the Structured Professional Judgement (SJP) approach. The checklist includes risk factors such as ‘origin from an area with known sub-cultural values’ and ‘lack of cultural integration’ and victim vulnerability factors, such as ‘extreme fear’ and ‘inadequate access to resources.’69,94 The tool considers the entire family unit as potentially part of the threat of violence, with research indicating most victims of honour-based violence are ex-wives and daughters.69 http://proactive-resolutions.com/shop/assessment-risk-honour-based-violence-patriarch/ |

Working with People from Diverse Cultures

Culture is defined as “a complex network of meanings entrenched within historical, social, economic, political processes” (p. 5).95 Because immigrants and refugees have widely varying pre- and post-migration experiences due to intersecting factors and identities, such as gender, race, nationality, immigration status, socioeconomic status, education, and language, a culturally-informed approach is needed, rather than a traditional ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach.

Best practice approaches to working with people from diverse cultures have been developed in a variety of contexts, including the health sector. There are several approaches that have been applied in working with immigrant and refugee populations in a variety of disciplines and sectors. These can be considered on a continuum, which on one end has harmful and ineffective approaches such as cultural destructiveness (that is, holding discriminatory and prejudicial attitudes toward clients from minority cultural groups) and cultural indifference (that is, ignoring cultural differences or adopting a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to service delivery). On the other end are culturally-responsive approaches, including cultural awareness, cultural sensitivity, cultural competence, cultural safety and cultural humility, that differ in terms of what is expected of service providers in working with clients from different cultural backgrounds.

Cultural awareness means being aware of cultural differences. Cultural sensitivity means being sensitive to these differences when delivering services. Cultural competence reflects competence in working cross-culturally, without requiring a level of competence with respect to all cultures.96 Cultural proficiency extends further than competence and involves efforts to improve services based on the identified culturally-specific needs of clients.

Concepts that have emerged from work with Indigenous communities, particularly in the health sector, such as cultural safety and cultural humility, are also relevant to work with immigrant and refugee populations. Cultural safety is defined by clients themselves, and requires service providers to recognize that structures and systems themselves may threaten client safety, and make an effort to transfer power to clients.95

Cultural humility extends this concept further, and asks service providers to recognize that their own cultural values impact the services they provide. Cultural humility involves “a lifelong commitment to self-evaluation and self-critique [and] to redressing the power imbalances” (p. 117) between service providers and clients, and respectful processes built on mutual trust.97

In this Brief, the term culturally-informed is used to refer to risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning strategies that are informed by and reflective of different cultural perspectives of domestic violence and homicide, while the term culturally-specific is used to refer to risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning strategies and tools that have been developed for use with specific cultural groups.

Risk Management with Perpetrators from Immigrant and Refugee Populations

Risk management involves strategies such as monitoring and supervision, counselling and education, and addressing other factors associated with domestic violence and homicide, including mental health and substance use issues. It is clear that there is a need for dedicated resources and intervention programs targeting men who perpetrate domestic violence, including immigrant and refugee perpetrators.11,23,98,141 Yet, research points to a lack of counselling options available to immigrant and refugee men who perpetrate domestic violence.99

Research strongly supports the development of domestic violence intervention programs that are culturally-informed and inclusive of immigrant and refugee men, and culturally-specific programs for abusive immigrant and refugee men.10,33,68,98,100 It is particularly important that culturally-specific interventions are tailored to specific cultural groups to ensure they are culturally-appropriate and effective.101,102

Core components of domestic violence treatment programs for immigrant and refugee men include addressing discrimination and exclusion, exploring perpetrators’ own experiences of victimization and trauma, discussing cultural values, challenges, post-migration gender role transitions, and enhancing acculturation.7,13,39,103 Education for perpetrators should focus on the meaning of loss of social and economic status, gender equality to counter traditional beliefs (e.g., that men have a right to control women), and the roots of men’s jealousy.17,104 Differences in settlement experiences between urban and rural communities should also be considered.7

Strong relationships with service providers are critical to effective support and intervention with immigrant and refugee men.103 They may also need support with other issues that may create stress for them post-migration, including securing employment in the host country.104,105

Preventing Domestic Violence Perpetration

Men and boys should be targeted in domestic violence prevention and education initiatives within immigrant and refugee populations (e.g., during the immigration process, post-migration).11,43,106,141 Research suggests that domestic violence education programs may be more effective if they are facilitated by immigrant and refugee men and/or in partnership with immigrant communities.28,38

Other researchers have suggested different approaches to domestic violence prevention; for example, men with domestic violence convictions should not be allowed to bring spouses overseas or sponsor their intimate partners.107,108 For marriage migrants (previously referred to “mail-order brides”) in particular, a lack of information about their new partners can put them at risk of domestic violence; so access to important information pre-migration could reduce the risk of violence perpetrated against them.108

Cultural Navigators – REACH Immigrant and Refugee Initiative (RIRI)

A team of ‘cultural navigators’ is working closely with newcomers and police in Edmonton, Alberta, to prevent domestic violence in immigrant communities. These respected community leaders are involved in the delivery of public education to immigrant communities on domestic violence and the Canadian criminal justice system, the development of tools for front-line workers and community leaders on responding to domestic violence in immigrant and refugee communities, and the development of culturally-appropriate domestic violence services and supports.

A team of ‘cultural navigators’ is working closely with newcomers and police in Edmonton, Alberta, to prevent domestic violence in immigrant communities. These respected community leaders are involved in the delivery of public education to immigrant communities on domestic violence and the Canadian criminal justice system, the development of tools for front-line workers and community leaders on responding to domestic violence in immigrant and refugee communities, and the development of culturally-appropriate domestic violence services and supports.

Barriers to Disclosure and Support for Immigrant and Refugee Women

Immigrant women report greater barriers to leaving domestic violence than non-immigrant women,109 and face many cultural, institutional, and structural barriers to disclosing and accessing support services.11,14,19,21-24,26,28,35,37,45,51,55,58,68,70-71,83,

85-87,101,106,108,110-131,134,142

These include:

- Collectivist cultural beliefs

- Concerns about confidentiality

- Desire to keep family intact

- Stigma and shame surrounding divorce

- Distrust of authorities and the criminal justice system (e.g., due to negative experiences in their country of origin)

- Economic dependency on abuser

- Experiences of racism, and fear of being ostracized or contributing to racial discrimination and xenophobia by disclosing domestic violence and/or seeking services

- Fear of deportation (self or perpetrator)

- Fear of separation from, or loss of, children

- Geographic, social, and cultural isolation

- Lack of awareness about available domestic violence services

- Lack of coordinated services

- Lack of culturally and linguistically appropriate services, particularly in rural communities

- Language barriers and lack of translation and interpretation services

- Limited knowledge of immigration laws and rights

- Precarious immigration status

- Stigma, shame, and silence surrounding domestic violence, and family privacy

Immigrant women are more likely to access domestic violence support services if people they care about (e.g., other family members) are at risk.109 In fact, risk to children is one of the strongest motivators for women to take action in response to domestic violence.37,83,132-134 Research therefore suggests more supportive, and less punitive, responses from the child welfare system as immigrant and refugee women struggle to settle in a new country, while maintaining safety for themselves and their children.115

Immigrant and refugee women may be reluctant to use mainstream domestic violence services that inadequately account for, or are outright dismissive of, their cultural values and their complex, intersecting needs.110,114 For example, if services are not offered in their own language, or women experience stigma and discrimination from service providers and other clients, this can make services feel unwelcoming. Therefore, culturally-sensitive services are needed that recognize and take into consideration the specific contexts, experiences, and needs of abused immigrant and refugee women.67,110

A Culturally-Informed Approach to Domestic Violence Services for Survivors

Understanding the cultural contexts and impacts of domestic violence within immigrant and refugee populations is important for enhancing the safety of survivors. Service providers should also identify ways in which culture can be a source of strength and support for intervention in cases of domestic violence.68,85

Support groups may be particularly important for immigrant and refugee women because they reduce social isolation and enhance social connection.139-141 Domestic violence services and support groups for survivors must also find ways to be inclusive of women who have used violence against their abusive partners.142

Other Supports Needed to Improve Safety

Immigrant and refugee women are likely to benefit from a wide array of supports.46,106,143 For example, they may need legal assistance to navigate the immigration and/or criminal justice systems (e.g., seeking protection orders), advocacy to facilitate access to health care, and support to pursue education and/or employment opportunities to increase their economic independence.10,16,17,55,57,101,108,110,122,128,140-141,144

Targeting English language proficiency is particularly important to addressing risk and safety for immigrant and refugee women.16,21 Other services and supports that may enhance immigrant and refugee women’s safety include transportation and child care.17,108

Emerging research also highlights the significant barriers immigrant and refugee women face in accessing safe housing in Canada, and the critical need for housing for survivors of domestic violence.16,107,145-148 Immigrant and refugee women may require longer stays in transition housing,143 and that shelter stays play an important role in reducing risk of domestic violence and homicide.57

Safety Planning with Immigrant and Refugee Women

Safety planning with immigrant and refugee populations requires that multiple intersecting factors and needs be addressed simultaneously. Strategies must address survivors’ culturally-specific needs and unique individual circumstances (e.g., immigration status, language barriers, available formal and informal resources). 9,149 Given the pressures to keep families together and shame associated with divorce in some cultural groups, safety planning for immigrant and refugee populations must include strategies to increase safety for survivors who do not plan to leave their abusers.46,101,119 Women should also be informed about risk factors for severe, escalating, and potentially lethal violence.150

Cross-Sector Collaboration

The value of culturally-safe and collaborative approaches is that they create pathways for abused immigrant and refugee women to disclose experiences of domestic violence and express their concerns and needs.151 Settlement workers serve as an important resource for women experiencing violence, especially for women who are unlikely to access anti-violence services or seek support outside their cultural community.107 Collaboration between anti-violence services, settlement services, and immigrant communities is therefore critical to enhance domestic violence supports for immigrant and refugee women.11,25,55,114,142,152-153 Collaboration is also needed between mainstream and multicultural anti-violence agencies to reduce culturally-specific risk factors and barriers to support.114 Advocacy plays an important role in responding to domestic violence in immigrant and refugee populations.3

Service providers should collaborate with the education and health sectors, given the important role educators and health providers can play in immigrant and refugee women’s help-seeking.14,58,83,154-157 Safety planning should also involve cultural and religious institutions and leaders who can support survivors in seeking formal supports and contribute to outreach efforts.10,19-20,23-24,37,49,56,58,65,68,83,101,107,108,141,158-160 Religious leaders may benefit from domestic violence training and collaboration with anti-violence agencies, particularly given they may feel ill prepared to respond to domestic violence.3,23,143,161 Formal domestic violence services can better support women by identifying and collaborating with existing informal supports.117,162

Community Awareness

Raising awareness through health promotion efforts and culturally-appropriate education about domestic violence and healthy relationships, women’s rights, and support services is an important step toward increasing safety for immigrant and refugee populations.14,19,23,25,41,83,105,110,119,122,163 Community involvement in domestic violence prevention initiatives is critical in order to increase community leadership and engagement, reduce language barriers, and enhance community capacity to support survivors.11,27,38,52,160 Education should involve grassroots organizations, but also religious and community leaders.49,85,163 Education and awareness for women should be culturally-appropriate and empowerment-based, with a focus on women’s rights, understanding the relationship between stage of settlement and risk for domestic violence, and information about local domestic violence services.33,36,49-50,87,102,128,158,159,164-166

Below are some Canadian public/community awareness and education campaigns:

|

Immigrant and Refugee Communities Neighbours, Friends & Families (IRCNFF) |

|

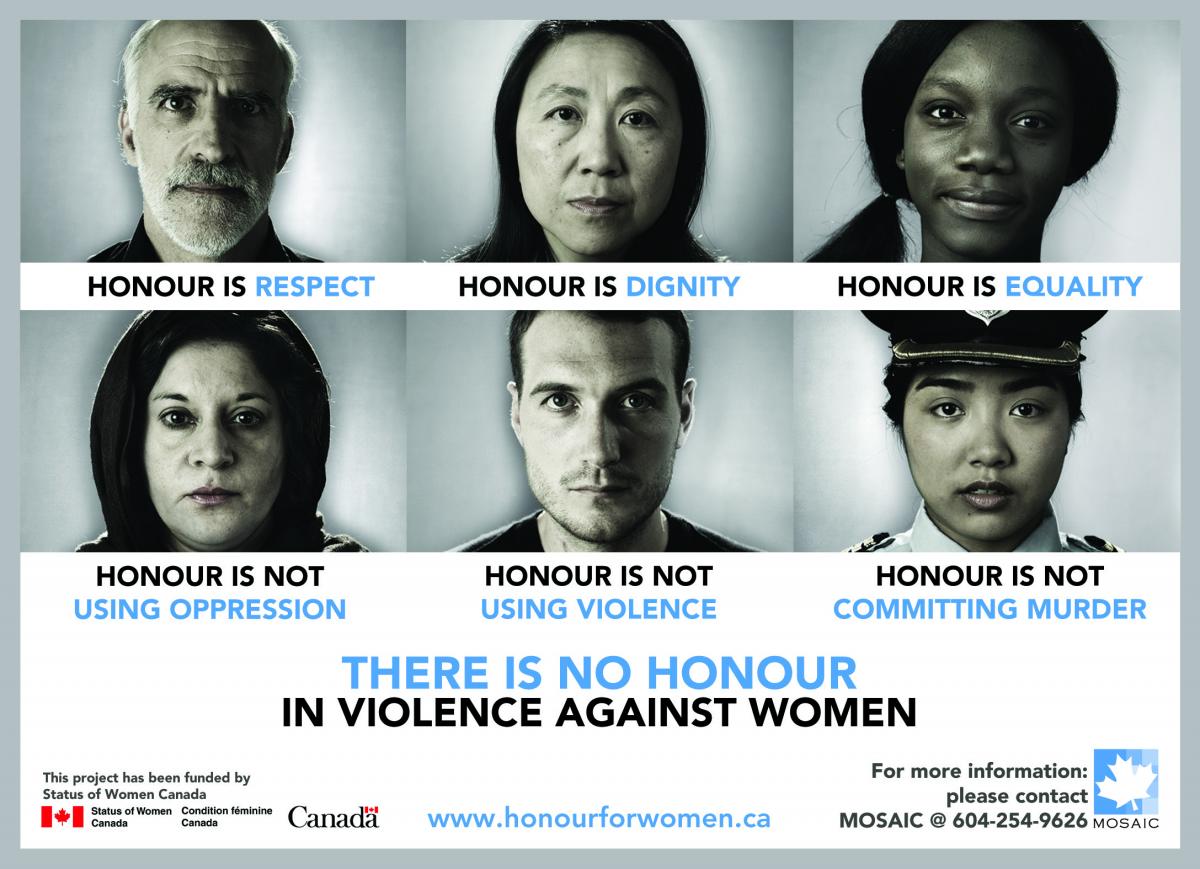

Preventing and Reducing Violence Against Women and Girls in the Name of “Honour” |

|

It’s a Choice: Forced Marriage is a Form of Violence |

|

Muslims for White Ribbon |

Considerations for Involving Family and Community Members in Risk Management and Safety Planning

When working with immigrant and refugee populations, it is important to consider how the involvement of family members may serve to increase risk and/or safety. The involvement of family and community members depends on the level of risk and the survivor’s level of connection with her culture of origin and/or her religion.

Research suggests that risk management and safety planning strategies for immigrant and refugee populations can be enhanced by involving family and community members, who may be in a position to provide informal support and resources.56,68 However, family unity and cohesion are highly valued in some cultures, and involving families in risk management and safety planning may increase risk for some survivors.34 Immigrant and refugee women may face extraordinary pressure from their families and/or faith communities to stay with abusive partners.136 Research indicates, for example, that Latina immigrant survivors may suffer domestic violence for longer periods or stay in abusive relationships for longer durations as a result of ‘familismo,’ a core cultural value that speaks to the importance of immediate and extended family relationships and the involvement of family in daily life and decision-making.16,26,56,71,83,158,167 On the other hand, familismo may be a protective factor, with Latina immigrant women seeking informal support from family members.56,167 It is important to respect a survivor’s cultural and familial connections when developing culturally-sensitive safety plans with immigrant and refugee women.46 However, it is also important to discuss the risks associated with involving family and community members in risk management and safety planning strategies within immigrant and refugee populations.

The Muslim Resource Centre for Social Support and Integration (MRCSSI) in London, Ontario, has developed a model of response to domestic violence called the Coordinated Organizational Response Team (CORT). This model works with a collectivist approach to provide holistic circles of supports. The Fours Aspects Screening Tool (FAST) determines the level of risk in the continuum of violence as well as strengths, including strengths and resources within the family and community. Based on this assessment, and in consultation with the survivor, CORT will decide who needs to be part of the FAST process and how and who in the family or community (including, for example, religious and cultural leaders) could and should be involved to support the survivor.

Enhancing Culturally Integrative Family Safety Response in Muslim Communities

Mohammed Baobaid & Lynda M. Ashbourne (2016)

This book presents the Culturally Integrative Family Safety Response (CIFSR) model that is currently being used by the Muslim Resource Centre for Social Support and Integration (MRCSSI) in London, Ontario. Created to support immigrant and newcomer families from collectivist backgrounds struggling with issues related to pre-migration trauma, family violence, and child protection concerns, the CIFSR model focuses on early risk-identification and intervention methods, preserving safety, and appropriate conflict responses. Also included is a Q&A chapter from the authors that invites helping professionals, educators, and other readers to apply the model globally.

Community-Based Research and Resources

|

Building Supports: Housing Access for Immigrant and Refugee Women Leaving Violence The Building Supports project is a three-year community-based project by the BC Non-Profit Housing Association, BC Society of Transition Houses, & the FREDA Centre for Research on Violence Against Women and Children. The focus of the project is to understand the barriers to accessing secure and affordable housing for immigrant and refugee women leaving violent relationships. The project has produced a promising practices guide now available online, policy recommendations, a public awareness campaign, and an intersectional policy analysis of immigration/settlement, housing, and health sectors. |

|

Caring for Kids New to Canada Caring for Kids New to Canada is a guide developed by the Canadian Paediatric Society to help health professionals working with immigrant and refugee children and youth. The guide contains information and resources on assessment and screening; medical conditions; mental health and development; health promotion; culture and health; navigating the health system; and education and advocacy. Issues around domestic violence are included. |

|

Overcoming Barriers: A Coordinated Response to Violence Against Immigrant Women in New Brunswick This project aims to assess and understand the current systemic and structural barriers including the state of public services for immigrant women experiencing domestic violence in New Brunswick; and develop and implement a coordinated response. The project has completed a needs assessment report which is available online. |

|

The Safety of Immigrant, Refugee, and Non-Status Women Project The Safety of Immigrant, Refugee, and Non-Status Women Project was developed in partnership with Ending Violence Association of BC, MOSAIC, and Vancouver Lower Mainland Multicultural Family Support Services to address policy gaps that compromise the safety of immigrant, refugee, and non-status women who experience violence. The project contains many resources including: a literature review; provincial and federal briefing notes; resource guides; focus groups summaries; and links to other law foundation projects. |

|

Without Consent: Strategies for Identifying and Managing Risk in Cases of Forced Marriage The Enhancing Community Capacity to Respond to and Prevent Forced Marriage project by MOSAIC and Ending Violence Association of BC developed a risk assessment framework informed by a literature review, online survey, focus groups, key informant interviews and feedback from pilot studies. The purpose of the framework is to help service providers identify and respond to cases of forced marriage and to increase awareness about the dynamics and dangers associated with forced marriage. The framework is designed for use by settlement and anti-violence workers. The project also developed a website to disseminate the framework widely amongst service providers. The website also provides information on support services and protective practices to those who may be facing, or know someone facing forced marriage. |

|

Canadian Council for Refugees (CCR) – Violence against Non-status, Refugee and Immigrant Women The CCR is an organization committed to the rights and protection of refugees and other vulnerable migrants in Canada and internationally and to the settlement of refugees and immigrants in Canada. The CCR provides information and resources to help immigrants and refugees experiencing violence secure status in Canada and access protection. |

References

- Han, J. H. J. (2009). Safety for immigrant, refugee and non-status women: A literature review. Retrieved from http://endingviolence.org/files/uploads/IWP_Lit_Review_ for_website_May_2010.pdf

- Ending Violence Association of British Columbia, Vancouver, Mosaic, & Lower Mainland Multicultural Family Support Services Society. (2011). Immigrant women’s project: Safety of immigrant, refugee, and non-status women. Retrieved from http:// endingviolence.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/ IWP_Resource_Guide_FINAL.pdf

- Hancock, T. U., & Ames, N. (2008). Toward a model for engaging Latino lay ministers in domestic violence intervention. Families in Society, 89(4), 623-630.

- Lee, Y.-S., & Hadeed, L. (2009). Intimate partner violence among Asian immigrant communities Health/mental health consequences, help-seeking behaviors, and service utilization. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 10(2), 143-170.

- International Organization for Migration. (2017). Key migration terms. Retrieved from https://www.iom.int/key-migration-terms

- United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. (2017). Social and Human Sciences, International Migration. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/new/en/social-and-human- sciences/themes/international-migration/glossary/ migrant/

- Hancock, T. U., & Siu, K. (2009). A culturally sensitive intervention with domestically violent Latino immigrant men. Journal of Family Violence, 24(2), 123-132.

- Menjívar, C., & Salcido, O. (2002). Immigrant women and domestic violence common experiences in different countries. Gender & Society, 16(6), 898-920.

- Wood, J., Light, L., Ruebsaat, G., Turner, D., Novakowski, M., & Walsh, W. (2008, April 16). Keeping women safe: Eight critical components of an effective justice response to domestic violence. Retrieved from http://endingviolence.org/files/uploads/ KeepingWomenSafe0416.pdf

- Abu-Ras, W. (2007). Cultural beliefs and service utilization by battered Arab immigrant women. Violence Against Women, 13(10), 1002-1028. http://dx.doi. org/10.1177/1077801207306019

- Ben-Porat, A. (2010). Connecting two worlds: Training social workers to deal with domestic violence against women in the Ethiopian community. The British Journal of Social Work, 40(8), 2485-2501. doi.org/10.1093/ bjsw/bcq027

- Brownridge, D. A., & Halli, S. S. (2002). Double jeopardy? Violence against immigrant women in Canada. Violence & Victims 17(4), 455- 471.

- Edelstein, A. A. (2013). Culture transition, acculturation and intimate partner homicide. SpringerPlus, 2(1), 338-350. doi:10.1186/2193-1801-2- 338

- Fernbrant, C., Essén, B., Östergren, P.-O., & Cantor-Graae, E. (2011). Perceived threat of violence and exposure to physical violence against foreign-born women: A Swedish population-based study. Women’s Health Issues, 21(3), 206-213.

- Galvez, G., Mankowski, E. S., McGlade, M. S., Ruiz, M. E., & Glass, N. (2011). Work-related intimate partner violence among employed immigrants from Mexico. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 12(3), 230-246. http://dx.doi. org/10.1037/a0022690

- Hass, G. A., Dutton, M. A., & Orloff, L. E. (2000). Lifetime prevalence of violence against Latina immigrants: Legal and policy implications. International Review of Victimology, 7, 93-113.

- Hyman, I., Mason, R., Guruge, S., Berman, H., Kanagaratnam, P., & Manuel, L. (2011). Perceptions of factors contributing to intimate partner violence among Sri Lankan Tamil immigrant women in Canada. Health Care Women Int, 32(9), 779-794. doi:10.1080/07399332.2011.569220

- Jin, X., & Keat, J. (2010). The effects of change in spousal power on intimate partner violence among Chinese immigrants. J Interpers Violence, 25(4), 610-625. doi:10.1177/0886260509334283

- Keller, E. M., & Brennan, P. K. (2007). Cultural considerations and challenges to service delivery for Sudanese victims of domestic violence: Insights from service providers and actors in the criminal justice system. International Review of Victimology, 14(1), 115-141.

- Kim, J. Y., & Sung, K.-t. (2000). Conjugal violence in Korean American families: A residue of the cultural tradition. Journal of Family Violence, 15(4), 331-345.

- Klevens, J. (2007). An overview of intimate partner violence among Latinos. Violence Against Women, 13(2), 111-122. doi:10.1177/1077801206296979

- Kim, C., & Sung, H. (2016). Characteristics and risk factors of Chinese immigrant intimate partner violence victims in New York City and the role of supportive networks. The Family Journal, 24(1), 60-69.

- Kulwicki, A., Aswad, B., Carmona, T., & Ballout, S. (2010). Barriers in the utilization of domestic violence services among Arab immigrant women: Perceptions of professionals, service providers & community leaders. Journal of Family Violence, 25(8), 727-735. http://dx.doi. org/10.1007/s10896-010-9330-8

- Lee, E. (2007). Domestic violence and risk factors among Korean immigrant women in the United States. Journal of Family Violence, 22(3), 141-149. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10896- 007-9063-5

- Lee, M. Y. (2000). Understanding Chinese battered women in North America: A review of the literature and practice implications. Journal of Multicultural Social Work, 8(3-4), 215-241. doi: 10.1300/J285v08n03_03

- Lewis, M., West, B., Bautista, L., Greenberg, A. M., & Done-Perez, I. (2005). Perceptions of service providers and community members on intimate partner violence within a Latino community. Health Education & Behavior, 32(1), 69-83. http://dx.doi. org/10.1177/1090198104269510

- Sheikh, N. S. (2008). A matter of faith: Muslim women’s perception of their faith community’s response to intimate partner violence (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Wright University, Dayton, OH.

- Baobaid, M. (n.d.). Guidelines for service providers: Outreach strategies for family violence intervention with immigrant and minority communities: Lessons learned from the Muslim Family Safety Project. Changing Ways. Retrieved from www.yemenembassy.ca/doc/Outreach%20 Strategies.pdf

- Foster, R. M. P. (2001). When immigration is trauma: Guidelines for the individual and family clinician. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 71(2), 153-170.

- Nicolson, B. L. (1997). The influence of premigration and postmigration stressors on mental health: A study of Southeast Asian refugees. Soc Work Res, 21(1), 19-31.

- Amanor-Boadu, Y. (2009). A comparison of immigrant and non-immigrant women’s decision making in abusive relationship (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS.

- Min, P. G. (2001). Changes in Korean immigrants’ gender role and social status, and their marital conflicts. Sociological Forum, 16(2), 301-320. doi:10.1023/a:1011056802719

- Morash, M., Bui, H. N., & Santiago, A. M. (2000). Cultural-specific gender ideology and wife abuse in Mexican-descent families. International Review of Victimology, 7(1-3), 67-91. doi:10.1177/026975800000700305

- Natarajan, M. (2002). Domestic violence among immigrants from India: What we need to know and what we should do. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 26(3), 301-321.

- Pan, A., Daley, S., Rivera, L. M., Williams, K., Lingle, D., & Reznik, V. (2006). Understanding the role of culture in domestic violence: The Ahimsa project for safe families. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 8(1), 35-43. http:// dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10903-006-6340-y

- Rees, S., & Pease, B. (2007). Domestic violence in refugee families in Australia: Rethinking settlement policy and practice. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 5(2), 1-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J500v05n02_01

- Rizo, C. F., & Macy, R. J. (2011). Help seeking and barriers of Hispanic partner violence survivors: A systematic review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 16(3), 250-264. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2011.03.004

- Simbandumwe, L., Bailey, K., Denetto, S., Migliardi, P., Bacon, B., & Nighswander, M. (2008). Family violence prevention programs in immigrant communities: Perspectives of immigrant men. Journal of Community Psychology, 36(7), 899-914.

- Welland, C., & Ribner. (2010). Culturally specific treatment for partner-abusive Latino men: A qualitative study to identify and implement program components. Violence and Victims, 25(6), 799-813. doi:10.1891/0886-6708.25.6.799

- Zannettino, L. (2012). “... There is no war here; it is only the relationship that makes us scared”: Factors having an impact on domestic violence in Liberian refugee communities in South Australia. Violence Against Women, 18(7), 807- 828. doi:10.1177/1077801212455162

- Adam, N. M. (2000). Domestic violence against women within immigrant Indian and Pakistani communities in the United States (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL.

- Baobaid, M. (2012). Domestic violence risks in families with collectivist values: Understanding cultural context. Retrieved from http://onlinetraining.learningtoendabuse.ca/sites/ default/files/lessons/Domestic%20Violence%20 Risks%20in%20Families%20with%20 Collectivist%20Values.pdf

- Celaya-Alston, R. C. (2010). Hombres en Accion (Men in Action): A community defined domestic violence intervention with Mexican immigrant men (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Portland State University, Portland, OR.

- Huerta, D. I. (2014). Family related attitudes and beliefs influencing risk and support seeking among female victims of domestic and sexual violence in El Paso, Texas (Unpublished Master’s Thesis). The University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, TX.

- Vaughan, C., Davis, E., Murdolo, A., Chen, J., Murray, L., Block, K., Quiazon, R., & Warr, D. (2015). Promoting community-led responses to violence against immigrant and refugee women in metropolitan and regional Australia: The ASPIRE Project (State of knowledge paper 7). Australia’s National Research Organization for Women’s Safety. Retrieved from: https://d2c0ikyv46o3b1.cloudfront.net/anrows.org.au/s3fs-public/12_1.2%2...

- Light, L. (2008). Empowerment of immigrant and refugee women who are victims of violence in their intimate relationships. Justice Institute of British Columbia. Retrieved from http:// www.jibc.ca/sites/default/files/research/pdf/ Empowerment%2520of%2520Immigrant%2 520and%2520Refugee%2520Women%2520-%2520Executive%2520Sum%E2%80%A6.pdf

- Lucknauth, C. (2014). Racialized immigrant women responding to intimate partner abuse. Retrieved from https://ruor.uottawa.ca/ handle/10393/30663

- Kimber, M. S., Boyle, M. H., Lipman, E. L., Colwell, S. R., Georgiades, K., & Preston, S. (2013). The associations between sex, immigrant status, immigrant concentration and intimate partner violence: Evidence from the Canadian General Social Survey. Global Public Health: An International Journal for Research, Policy and Practice, 8(7), 796-821. http://dx.doi.org/10.10 80/17441692.2013.814701

- Du Mont, J., Hyman, I., O’Brien, K., White, M. E., Odette, F., & Tyyskä, V. (2012). Factors associated with intimate partner violence by a former partner by immigration status and length of residence in Canada. Ann Epidemiol, 22(11), 772-777. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2012.09.001

- Hyman, I., & Forte. (2006). The association between length of stay in Canada and intimate partner violence among immigrant women. American Journal of Public Health, 96(4), 654. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2004.046409

- Hassan, G., Thombs, B., Rousseau, C., Kirmayer, L. J., Feightner, J., Ueffing, E., & Pottie, K. (2011). Appendix 13: Intimate partner violence: Evidence review for newly arriving immigrants. Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health. Retrieved from http://www.cmaj.ca/content/suppl/2010/06/07/ cmaj.090313.DC1/imm-ipv-13-at.pdf

- Hyman, I., Forte, T., Mont, J. D., Romans, S., & Cohen, M. M. (2006). Help-seeking rates for intimate partner violence (IPV) among Canadian immigrant women. Health Care Women Int, 27(8), 682-694. doi:10.1080/07399330600817618

- Nilsson, J. E., Brown, C., Russell, E. B., & Khamphakdy-Brown, S. (2008). Acculturation, partner violence, and psychological distress in refugee women from Somalia. J Interpers Violence, 23(11), 1654-1663. dio:10.2105/ ajph.2007.112813

- Adams, M. E., & Campbell, J. (2012). Being undocumented & intimate partner violence (IPV): Multiple vulnerabilities through the lens of feminist intersectionality. Women’s Health and Urban Life, 11(1), 15-34.

- Bhuyan, R., & Velagapudi, K. (2013). From one “dragon sleigh” to another: Advocating for immigrant women facing violence in Kansas. Affilia, 28(1), 65-78. http://dx.doi. org/10.1177/0886109912475049

- Brabeck, K. M., & Guzmán. (2009). Exploring Mexican-origin intimate partner abuse survivors’ help-seeking within their sociocultural contexts. Violence Vict, 24(6), 817-832. doi:10.1891/0886- 6708.24.6.817

- Cesario, S. K., Nava, A., Bianchi, A., McFarlane, J., & Maddoux, J. (2014). Functioning outcomes for abused immigrant women and their children four months after initiating intervention. Rev Panam Salud Publica, 35(1), 8-14.

- Moynihan, B., Gaboury, M. T., & Onken, K. J. (2008). Undocumented and unprotected immigrant women and children in harm’s way. J Forensic Nurs, 4(3), 123-129. doi:10.1111/j.1939- 3938.2008.00020.x

- Salcido, O., & Adelman, M. (2004). “He has me tied with the blessed and damned papers”: Undocumented-immigrant battered women in Phoenix, Arizona. Human Organization, 63(2), 162-172.

- Shaw, K. (2008). Barriers to freedom: Continued failure of US immigration laws to offer equal protection to immigrant battered women. Cardozo JL & Gender, 15, 663-689.

- Sokoloff, N. J. (2008). Expanding the intersectional paradigm to better understand domestic violence in immigrant communities. Critical Criminology, 16(4), 229-255. doi: 10.1007/ s10612-008-9059-3

- Vishnuvajjala, R. (2012). Insecure communities: How an immigration enforcement program encourages battered women to stay silent. Boston College Journal of Law & Social Justice, 32(1), 185-213.

- Dutton, M. A., Ammar, N., Orloff, L., & Terrell, D. (2007, April). Use and outcomes of protection orders by battered immigrant women. Retrieved from https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/218255.pdf

- Tahirih Justice Center. (n.d.). Policy recommendations to address forced marriage in the United States. Retrieved from https://preventforcedmarriage.org/wp-content/ uploads/2015/01/FMI-Policy-Recommendations1. pdf

- Cross, P. (2013). Violence against women: Health and justice for Canadian Muslim Women. Canadian Council of Muslim Women. Retrieved from www.ccmw.com/wp- content/uploads/2013/07/EN-VAW_web.pdf

- Aujla, W., & Gill, A. K. (2014). Conceptualizing ‘honour’ killings in Canada: An extreme form of domestic violence? International Journal of Criminal Justice Sciences, 9(1), 153-166.

- Yick, A. G., & Oomen, E. (2009). Using the PEN-3 model to plan culturally competent domestic violence intervention and prevention services in Chinese American and immigrant communities. Health Education, 109(2), 125-139. doi:10.1108/09654280910936585

- Shalabi, D., Mitchell, S., & Andersson, N. (2015). Review of gender violence among Arab immigrants in Canada: Key issues for prevention efforts. Journal of Family Violence, 30(7), 817-825. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10896-015-9718-6

- Belfrage, H., Strand, S., Ekman, L., & Hasselborg, A.-K. (2012). Assessing risk of patriarchal violence with honour as a motive: Six years experience using the PATRIARCH checklist. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 14(1), 20-29.

- Shiu-Thornton, S., Senturia, K., & Sullivan, M. (2005). “Like a bird in a cage”: Vietnamese women survivors talk about domestic violence. J Interpers Violence, 20(8), 959-976. doi:10.1177/0886260505277677

- Silva-Martínez, E. (2016). “El silencio”: Conceptualizations of Latina immigrant survivors of intimate partner violence in the Midwest the United States. Violence Against Women, 22(5), 523-544.

- Chokshi, R. (2007). South Asian immigrant women & abuse: Identifying intersecting issues and culturally appropriate solutions (Unpublished Master’s thesis). Ryerson University, Toronto, ON.

- Korteweg, A. C. (2012). Understanding honour killing and honour-related violence in the immigration context: Implications for the legal profession and beyond. Canadian Criminal Law Review, 16(2), 135-160.

- Korteweg, A. C. (2014). ‘Honour killing’ in the immigrant context: Multiculturalism and the racialization of violence against women. Politikon, 41(2), 183-208.

- Muhammad, A. (2012, January). Canadian Council of Muslim Women (CCMW) Position on Femicide [not honour killing]. Canadian Council for Muslim Women. Retrieved from http://ccmw.com/wp-content/ uploads/2013/06/ccmw_position_femicide_not_ honour_killing.pdf

- Muhammad, A. A. (2010, June). Preliminary Examination of so-called “honour killings” in Canada. Department of Justice Canada. Retrieved from http://www.justice.gc.ca/ eng/rp-pr/cj-jp/fv-vf/hk-ch/hk_eng.pdf

- Helms, B. L. (2015). Honour and shame in the Canadian Muslim community: Developing culturally sensitive counselling interventions. Canadian Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy, 49(2), 163-184.

- MOSAIC. (2015). Preventing and Reducing Violence Against Women and Girls in the Name of “Honour” Project. Retrieved from http://www.mosaicbc.org/resources/in-the-name-of-honour/

- Gill, A. (2008). ‘Crimes of honour’ and violence against women in the UK. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 32(2), 243-263.

- Alkahteeb, S. (n.d.). The Muslim Wheel of Domestic Violence. Retrieved from: http://projectsakinah.org/Family-Violence/ Understanding-Abuse/The-Muslim-Wheel-of- Domestic-Violence

- Campbell, M., Hilton, NZ., Kropp, PR., Dawson, M., & Jaffe, P. (2016). Domestic Violence Risk Assessment: Informing Safety Planning & Risk Management. Domestic Homicide Brief (2). London, ON: Canadian Domestic Homicide Prevention Initiative. ISBN 978-1- 988412-01-6

- Jaji, R. (2009). Masculinity on Unstable Ground: Young Refugee Men in Nairobi, Kenya. J Refug Stud, 22(2), 177-194.

- Acevedo, M. J. (2000). Battered immigrant Mexican women’s perspectives regarding abuse and help-seeking. Journal of Multicultural Social Work, 8(3-4), 243-282.

- Bui, H. N. (2003). Help-seeking behavior among abused immigrant women: A case of Vietnamese American women. Violence Against Women, 9(2), 207-239.

- Ely, G. E. (2004). Domestic violence and immigrant communities in the United States: A review of women’s unique needs and recommendations for social work practice and research. Stress, Trauma and Crisis: An International Journal, 7(4), 223-241. http:// dx.doi.org/10.1080/15434610490888027

- Mason, R., Hyman, I., Berman, H., Guruge, S., Kanagaratnam, P., & Manuel, L. (2008). “Violence is an international language”: Tamil women’s perceptions of intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women, 14(12), 1397-1412.

- Murdaugh, C., Hunt, S., Sowell, R., & Santana, I. (2004). Domestic violence in Hispanics in the southeastern United States: A survey and needs analysis. Journal of Family Violence, 19(2), 107-115.

- Chan, K. L. (2012). Predicting the risk of intimate partner violence: The Chinese risk assessment tool for victims. Journal of Family Violence, 27(2), 157-164.

- Chan, K. L. (2014). Assessing the risk of intimate partner violence in the Chinese population: The Chinese Risk Assessment Tool for Perpetrator (CRAT-P). Violence Against Women, 20(5), 500-516.

- Messing, J. T., Amanor-Boadu, Y., Cavanaugh, C. E., Glass, N. E., & Campbell, J. C. (2013). Culturally competent intimate partner violence risk assessment: Adapting the Danger Assessment for immigrant women. Social Work Research, 37(3), 263-275.

- Campbell, J. (n.d.). Impact of Culturally Specific Danger Assessment on Safety, Mental Health, and Empowerment. Retrieved from: http://popcenter.jhu.edu/projects/impact-of- culturally-specific-danger-assessment-on-safety- mental-health-and-empowerment/

- Richards, L. (2009). Domestic Abuse, Htalking and Harassment and Honour Based Violence (DASH, 2009) risk identification and assessment and management model. Retrieved from http://www.dashriskchecklist.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/DASH-2009.pdf

- Baobaid, M., & Ashbourne, L. M. (2017). Enhancing culturally integrative family safety response in Muslim communities. London, England: Routledge.

- Kropp, P. R., Belgrade, H., & Hart, S. D. (n.d.). Risk for Honour Based Violence (PATRIARCH). Retrieved from: http://proactive-resolutions.com/ shop/assessment-risk-honour-based-violence- patriarch/

- Yeung, S. (2016). Conceptualizing cultural safety: Definitions and applications of safety in health care for Indigenous mothers in Canada. Journal for Social Thought, 1(1), 1-13.

- Williams, O. J., & Jenkins, E. J. (2015). Minority judges’ recommendations for improving court services for battered women of color: A focus group report. Journal of Child Custody: Research, Issues, and Practices, 12(2), 175-191.

- Tervalon, M., & Murray-García, J. (1998). Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 9(2).

- Rana, S. (2012, February). Addressing domestic violence in immigrant communities: Critical issues for culturally competent services. National Online Resource Center on Violence Against Women. Retrieved from http://vawnet.org/print-document.php?doc_ id=3157&find_type=web_desc_AR

- Thandi, G. S. (2013). A tale of two clients: Criminal justice system failings in addressing the needs of South Asian communities of Surrey, British Columbia, Canada. South Asian Diaspora, 5(2), 211-221. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19438 192.2013.740227

- Echauri, J. A., Femántiez-Montalvo, J., Martínez, M., & Azkarate, J. M. (2013). Effectiveness of a treatment programme for immigrants who committed gender-based violence against their partners. Psicothema, 25(1), 49-54.

- Raj, A., & Silverman, J. (2002). Violence against immigrant women: The roles of culture, context, and legal immigrant status on intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women, 8(3), 367-398. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/ abs/10.1177/10778010222183107

- Shirwadkar, S. (2004). Canadian domestic violence policy and Indian immigrant women. Violence Against Women, 10(8), 860-879. doi:10.1077801204266310

- Parra-Cardona, J. R., Escobar-Chew, A. R., Holtrop, K., Carpenter, G., Guzmán, R., Hernández, D., & Ramírez, D. G. (2013). “En el grupo tomas conciencia (in group you become aware)”: Latino immigrants’ satisfaction with a culturally informed intervention for men who batter. Violence Against Women, 19(1), 107-132.

- Bui, H., & Morash, M. (2008). Immigration, masculinity, and intimate partner violence from the standpoint of domestic violence service providers and Vietnamese-origin women. Feminist Criminology, 3(3), 191-215. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1557085108321500

- Saez-Betacourt, A., Lam, B. T., & Nguyen, T. (2008). The meaning of being incarcerated on a domestic violence charge and its impact on self and family among Latino immigrant batterers. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 17(2), 130-156.

- Sullivan, M., Senturia, K., Negash, T., Shiu- Thornton, S., & Giday, B. (2005). “For us it is like living in the dark”: Ethiopian women’s experiences with domestic violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20(8), 922-940. doi:10.1177/0886260505277678

- Bhuyan, R., & Senturia, K. (2005). Understanding domestic violence resource utilization and survivor solutions among immigrant and refugee women: Introduction to the special issue. J Interpers Violence, 20(8), 895-901. doi:10.1177/0886260505277676

- Crandall, M., Senturia, K., Sullivan, M., & Shiu-Thornton, S. (2005). “No way out”: Russian-speaking women’s experiences with domestic violence. J Interpers Violence, 20(8), 941-958. doi:10.1177/0886260505277679

- Amanor-Boadu, Y., Messing, J. T., Stith, S. M., Anderson, J. R., O’Sullivan, C., & Campbell, J. (2012). Immigrant and non-immigrant women: Factors that predict leaving an abusive relationship. Violence and Victims, 18(5), 610-632.

- Bauer, H. M., Rodriguez, M. A., Quiroga, S. S., & Flores-Ortiz, Y. G. (2000). Barriers to health care for abused Latina and Asian immigrant women. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved, 11(1), 33-44.

- Erez, E., Adelman, M., & Gregory, C. (2009). Intersections of immigration and domestic violence: Voices of battered immigrant women. Feminist Criminology, 4(1), 32-56. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1557085108325413

- Guruge, S., & Humphreys, J. (2009). Barriers affecting access to and use of formal social supports among abused immigrant women. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 41(3), 64- 84.

- Hyman, I., Forte, T., Mont, J. D., Romans, S., & Cohen, M. M. (2006). Help-seeking rates for intimate partner violence (IPV) among Canadian immigrant women. Health Care Women Int, 27(8), 682-694. doi:10.1080/07399330600817618

- Burnman, E., Smailes, S. L., & Chantier, K. (2004). ‘Culture’ as a barrier to service provision and delivery: Domestic violence services for minoritized women. Critical Social Policy, 24(3), 332-357. doi:10.1177/0261018304044363

- Earner, I. (2010). Double risk: Immigrant mothers, domestic violence and public child welfare services in New York City. Evaluation and Program Planning, 33, 288-293. doi: 10.1016/j. eavlprogplan.2009.05.016

- Denham, A. C., Frasier, P. Y., Hooten, E. G., Belton, L., Newton, W., Gonzalez, P., Campbell, M. K. (2007). Intimate partner violence among Latinas in Eastern North Carolina. Violence Against Women, 13, 123-140. doi:10.1177/1077801206296983

- Hancock, T. (2006). Addressing wife abuse in Mexican immigrant couples: Challenges for family social workers. Journal of Family Social Work, 10(3), 31-50.

- Latta, R. E., & Goodman, L. A. (2005). Considering the interplay of cultural context and service provision in intimate partner violence: The case of Haitian immigrant women. Violence Against Women, 11(11), 1441-1464.

- Midlarsky, E., Venkataramani-Kothari, A., & Plante, M. (2006). Domestic violence in the Chinese and South Asian immigrant communities. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 1087, 279-300. doi:10.1196/annals.1385.003

- Pendleton, G. (2003). Ensuring fairness and justice for noncitizen survivors of domestic violence. Juvenile and Family Court Journal, 54(4), 69-85. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6988.2003.tb00087.x

- Reina, A. S., Lohman, B. J., & Maldonado, M. M. (2014). ‘He said they’d deport me’: Factors influencing domestic violence help-seeking practices among Latina immigrants. J Interpers Violence, 29(4), 593-615. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0886260513505214

- Sharma, A. (2001). Healing the wounds of domestic abuse: Improving the effectiveness of feminist therapeutic interventions with immigrant and racially visible women who have been abused. Violence Against Women, 7(12), 1405-1428.

- Shim, W. S., & Nelson-Becker, H. (2009). Korean older intimate partner violence survivors in North America: Cultural considerations and practice recommendations. Journal of Women & Aging, 21(3), 213-228. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08952840903054773

- Sokoloff, N. J., & Pearce, S. C. (2011). Intersections, immigration, and partner violence: A view from a new gateway- Baltimore, Maryland. Women & Criminal Justice, 21(3), 250-266.

- Vidales, G. T. (2010). Arrested justice: The multifaceted plight of immigrant Latinas who faced domestic violence. Journal of Family Violence, 25(6), 533-544.

- National Coalition Against Domestic Violence. (n.d.). Immigrant victims of domestic violence. Retrieved from http://www. ncdsv.org/images/NCADV_ImmigrantVictimsOfDV.pdf

- Novick, S., Yoshihama, M., Runner, M., & Fund, F. V. P. (2009, April). Intimate partner violence in immigrant and refugee communities: Challenges, promising practices, and recommendations. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Retrieved from http://www. policyarchive.org/handle/10207/21315

- Reina, A. (2010). Domestic violence in Iowa: Exploring the experiences of Latinas with organizational response (Unpublished Master’s thesis). Iowa State University, Ames, IA.

- Rishchynski, G. M. (2006). Disclosing abuse: The voices of Spanish-speaking women in Canada (Unpublished Master’s thesis). University of Toronto, Toronto, ON.

- Trijbetz, T. (2013, September). Domestic and family violence and people from immigrant and refugee backgrounds. Australian Domestic & Family Violence Clearinghouse. Retrieved from http://www.mhima.org.au/ pdfs/Domestic%20and%20family%20violence_ fact%20sheet%2011.pdf

- Washington State Coalition Against Domestic Violence. (2011, June). Immigrant and refugee victims of domestic violence homicide in Washington state. Washington State Domestic Violence Fatality Review. Retrieved from https://wscadv.org/resources/issue- brief-immigrant-refugee-victims-dv-homicide/

- Donnelly, S. L. (2015). Two sides of the same coin---a qualitative meta-study of factors influencing immigrant women’s experiences of intimate partner violence (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL.

- Kyriakakis, S. (2009). The role of cultural and structural factors in the manifestation of abuse and help seeking patterns for battered Mexican immigrant women (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Washington University, St. Louis, MO.

- Silva-Martinez, E. (2009). Understanding from the inside: A critical ethnographic view of help-seeking among battered Latinas in the Midwest of the United States (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). The University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA.

- Merchant, M. (2000). A comparative study of agencies assisting domestic violence victims: Does the South Asian community have special needs? Journal of Social Distress and the Homeless, 9(3), 249-259.

- Baobaid, M., & Hamed, G. (2010, December). Addressing domestic violence in Canadian Muslim communities: A training manual for Muslim communities and Ontario service providers. Muslim Resource Centre for Social Support and Integration. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/9739962/Addressing_ Domestic_Violence_within_Canadian_Muslim_ Communities

- Riley, K. M. (2011, September). Violence in the lives of Muslim girls and women in Canada: Symposium discussion paper. Retrieved from http://www.learningtoendabuse.ca/sites/default/files/Violence%20in%20the%20 Lives%20of%20Muslim%20Girls%20and%20 Women.pdf

- Tutty, L. M., Giurgiu, B., Traya, N., Weaver-Dunlop, G., & Christensen, J. (2010, April). Promising practices to engage ethno- cultural communities in ending domestic violence. RESOLVE Alberta. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/ profile/Leslie_Tutty/publication/258699644_Promising_Practices_to_Engage_Ethno-cultural_ Communities_in_Ending_Domestic_Violence/ links/00463528d7e151ed19000000/Promising- Practices-to-Engage-Ethno-cultural-Communities- in-Ending-Domestic-Violence.pdf

- Belknap, R. A., & Vandevusse, L. (2010). Listening sessions with Latinas: documenting life contexts and creating connections. Public Health Nurs, 27(4), 337-346. doi:10.1111/j.1525- 1446.2010.00864.x

- Molina, O., Lawrence, S. A., Azhar-Miller, A., & Rivera, M. (2009). Divorcing abused Latina immigrant women’s experiences with domestic violence support groups. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 50(7), 459-471.

- Shiu-Thornton, S., Senturia, K., & Sullivan, M. (2005). “Like a bird in a cage”: Vietnamese women survivors talk about domestic violence. J Interpers Violence, 20(8), 959-976. doi:10.1177/0886260505277677

- Bui, H. N. (2003). Help-seeking behavior among abused immigrant women: A case of Vietnamese American women. Violence Against Women, 9(2), 207-239.

- Bø Vatnar, S. K., & Bjørkly, S. (2010). An interactional perspective on the relationship of immigration to intimate partner violence in a representative sample of help-seeking women. J Interpers Violence, 25(10), 1815-1835. doi:10.1177/0886260509354511

- West Coast LEAF. (2012, May). Position paper on violence against women without immigration status. Retrieved from http:// ccrweb.ca/files/position_statement_-_women_ without_status_leaf.pdf

- BC Non-Profit Housing Association, BC Society of Transition Houses, & the FREDA Centre for Research on Violence Against Women and Children. (2015). Building supports project Phase 1 final report: Housing access for immigrant and refugee women leaving violence. Retrieved from https://bcsth.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/ BuldingSupportPhase1FinalReport1.pdf

- Tabibi, J., & Baker, L. L. (2017). Exploring the intersections: Immigrant and refugee women fleeing violence and experiencing homelessness in Canada – Meeting summary report. London, ON: Centre for Research & Education on Violence Against Women & Children. Retrieved from http://www.vawlearningnetwork.ca/sites/ vawlearningnetwork.ca/files/ESDC-CREVAWC- Meeting-Report-FINAL-August-9.pdf

- Thurston, W. E., Roy, A., Clow, B., Este, D., Gordey, T., Haworth-Brockman, M., McCoy, L., Beck, R. R., Saulnier, C., & Lesley, C. (2013). Pathways into and out of homelessness: Domestic violence and housing security for immigrant women. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 11(3), 278-298. doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2013.801734

- Rossiter, K., & Godard. L. (2014). Building supports: Housing access for immigrant and refugee women leaving violence. Cultures West, 32(2), 18.

- Community Coordination for Women’s Safety and Ending Violence Association of British Columbia. (2013). Safety planning across culture & community: A guide for front line violence against women responders. Retrieved from http://endingviolence.org/files/ uploads/ure_and_Community_Manual_-_EVA_BC_ Dec_9_2013.pdf

- Zarza, M. J., Ponsoda, V., & Carrillo, R. (2009). Predictors of violence and lethality among Latina immigrants: Implications for assessment and treatment. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 18(1), 1-16. http://dx.doi. org/10.1080/10926770802616423

- Orloff, L. E. (2014). Interviewing and safety planning for immigrant victims of domestic violence. Legal Momentum: The Women’s Legal Defense and Education Fund. Retrieved from http://library.niwap.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/ CULT-Man-Ch2-InterviewingSafetyPlanningImmVi ctimsDV-09.23.14.pdf

- Ending Violence Association of BC. (2014). Working together to end violence against women. Cultures West, 32(2), 11-13.

- Ahmadzai, M. (2014). A study on visible minority immigrant women’s experiences with domestic violence (Unpublished Masters thesis). Wilfrid Laurier University, Waterloo, ON.

- Kelly, U. (2006). “What will happen if I tell you?” Battered Latina women’s experiences of health care. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 38(4), 78-95.

- Taft, A. J., Small, R., & Hoang, K. A. (2008). Intimate partner violence in Vietnam and among Vietnamese diaspora communities in Western societies: A comprehensive review. Journal of Family Studies, 14(2-3), 167-182.

- Shuman, S. J. (2014). Intimate partner violence among undocumented Spanish-speaking immigrants: Prevalence and help-seeking behaviors in Philadelphia (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Temple University, Philadelphia, PA.

- Vives-Cases, C., La Parra, D., Goicolea, L., Felt, E., Briones-Vozmediano, E., Ortiz-Barreda, G., & Gil-Gonzalez, D. (2014). Preventing and addressing intimate partner violence against migrant and ethnic minority women: The role of the health sector. World Health Organization. Retrieved from http://www.euro.who.int/ data/assets/pdf_file/0018/270180/21256- WHO-Intimate-Partner-Violence_low_V7.pdf

- Fuchsel, C. L. M., Murphy, S. B., & Dufresne, R. (2012). Domestic violence, culture, and relationship dynamics among immigrant Mexican women. Affilia, 27(3), 263-274.

- Liao, M. S. (2006). Domestic violence among Asian Indian immigrant women: Risk factors, acculturation, and intervention. Women & Therapy, 29(1-2), 23-40.

- Uehling, G., Bouroncle, A., Roeber, C., Tashima, N., & Crain, C. (n.d.). Preventing partner violence in refugee and immigrant communities. Forced Migration Review. Retrieved from http:// www.fmreview.org/sites/fmr/files/FMRdownloads/ en/technology/50-51.pdf

- Choi, Y. J. (2015). Determinants of clergy behaviors promoting safety of battered Korean immigrant women. Violence Against Women, 21(3), 394-415.

- Community Coordination for Women’s Safety. (2007, January 16). Immigrant, refugee and non-status women and violence against women in relationships. Retrieved from http://endingviolence.org/files/ uploads/Imm_Ref_Women_Violence.pdf