Preventing Domestic Homicide in Canada: Current Knowledge on Risk Assessment, Risk Management and Safety Planning with Vulnerable Populations

Canadian Domestic Homicide Prevention Initiative with Vulnerable Populations (CDHPIVP) Literature Review on Risk Assessment, Risk Management and Safety Planning

Overall authorship (editors):

Nicole Jeffrey, Jordan Fairbairn, Marcie Campbell, Myrna Dawson, Peter Jaffe, Anna-Lee Straatman

Acknowledgements:

| Research Assistants/Students | ||

|

Abir Al Jamal Danielle Bader Keri Cheechoo Randal David Nichole Faller Meghan Gosse Chelsea Heron |

Nicole Jeffrey Anna Johnson Sakthi Kalaichandran Natasha Lagarde Laura Olszowy Olivia Peters Katherine Reif |

Kayla Sapardanis Mike Saxton Sara Straatman Melissa Wuerch Sarah Yercich |

| Editor | ||

| Jaellayna Palmer | ||

| Graphic Designer | ||

| Elsa Barreto | ||

Suggested Citation:

Jeffrey, N., Fairbairn, J., Campbell, M., Dawson, M., Jaffe, P. & Straatman, A-L. (November 2018). Canadian Domestic Homicide Prevention Initiative with Vulnerable Populations (CDHPIVP) Literature Review on Risk Assessment, Risk Management and Safety Planning. London, ON: Canadian Domestic Homicide Prevention Initiative. ISBN: 978-1-988412-27-6

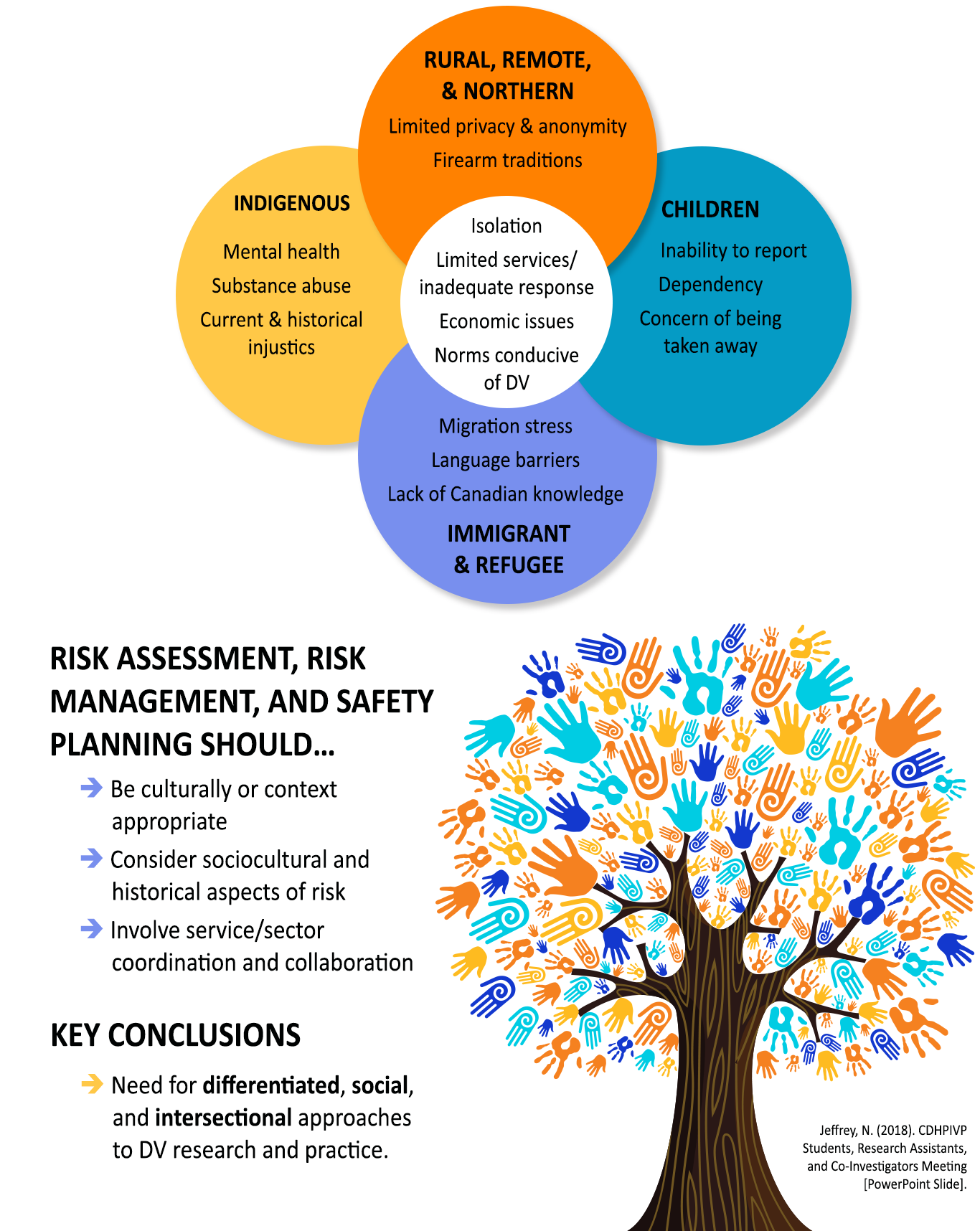

This literature review has identified vulnerabilities for domestic homicide within four specific populations: Indigenous peoples; immigrants and refugees; rural, remote, and northern communities; and children exposed to domestic violence. Although each population can have distinct vulnerabilities for domestic homicide, these populations also share common risk factors for experiencing domestic violence and homicide. To address these vulnerabilities and risks, the literature recommends that risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning be culturally or context appropriate; consider the sociocultural and historical aspects of risk; and involve service/sector coordination and collaboration. Overall, the literature identified a need for differentiated, social, and intersectional approaches to domestic violence and homicide research and practice.

Dear Reader:

This is a living document, which means that it will be regularly updated as new research and/or information becomes available. What you will read here is the result of efforts by the Canadian Domestic Homicide Prevention Initiative with Vulnerable Populations to provide a current and comprehensive assessment of the state of research and common or accepted practices related to domestic homicide and risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning with vulnerable populations. This research literature is voluminous and diverse, posing challenges for identifying and summarizing all the relevant information. We adopted a rigorous approach to identifying and assessing the relevance of literature that is discussed in more detail below. While we have strived to include and capture all relevant material through this process, there is no doubt that we have missed important information, making it crucial that this be considered a living document. As such, after you review the inclusion criteria contained in the methodology section, if you feel we have overlooked information, please let us know. Our goal is to ensure that we ultimately capture all the literature that can be useful to those experiencing domestic violence as well as those working with them to reduce their future exposure.

Contents

Overview of Risk Assessment, Risk Management, and Safety Planning

Risk Assessment, Risk Management, and Safety Planning with Vulnerable Populations

- Indigenous Population

- Rural, Remote, and Northern (RRN) populations

- Immigrant and Refugee Populations

- Children Exposed to Domestic Violence

An Intersectional Review with the Vulnerable Populations

- Immigrants and Refugees

- Indigenous Populations

- Rural, Remote, and Northern Populations

- Indigenous Rural, Remote, and Northern Populations

- Immigrant Rural, Remote, and Northern Populations

- Children Exposed to Domestic Violence

- Intersectional Policy and Practice

- The Need for Differentiated, Social, and Intersectional Approaches

- Priorities for Future Research and Practice

Introduction

Authors: Nicole Jeffrey

Contributors: Jordan Fairbairn

Nationally and internationally, domestic violence is consistently identified as one of the most common forms of gender-based violence and a significant public health problem (Johnson & Dawson, 2011; World Health Organization, 2012, 2016). In rare cases, domestic violence can escalate and result in domestic homicide (Campbell et al., 2003). International and national statistics consistently indicate that women are at greater risk than men of experiencing severe domestic violence and homicide (Burczycka & Conroy, 2017; United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2013). This is also reflected in much of the literature reviewed for this report. Therefore, this report will have a gendered focus with women being survivors/victims of domestic violence and homicide and with men being perpetrators.

This literature review focuses on four populations that experience vulnerabilities for domestic violence and homicide, as well as historical and ongoing factors of marginalization: (1) Indigenous populations; (2) immigrant and refugee populations; (3) rural, remote, and northern populations; and (4) children exposed to domestic violence and homicide. These are not mutually exclusive groups, as individuals may be members of multiple overlapping and intersecting groups. Additionally, these are not the only populations that should be considered vulnerable in the context of domestic violence. Research has identified other marginalized groups who experience vulnerability for domestic violence and homicide including the LGBTQ community (Hansen & Wells, 2015; Loveland & Raghavan, 2014); older women (Sutton & Dawson, 2017; Finfgeld-Connett, 2014); and women with disabilities (Perreault, 2009). However, this literature review represents a starting point to moving beyond general approaches to domestic violence risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning to consider the specific experiences and challenges of various groups.

Why are we starting with these four identified groups? In Canada, Indigenous Peoples and individuals living in rural, remote, and northern communities are at an increased risk of domestic violence and homicide compared to non-Indigenous and urban populations (Northcott, 2011; Statistics Canada, 2006; Statistics Canada, 2016). Immigrants in Canada have lower overall levels of domestic violence compared to non-immigrants. However, this lower risk does not persist when other factors are considered, and the barriers they face may impact their levels of self-reported and police-reported domestic violence (Du Mont & Forte, 2012; Sinha, 2013). These barriers include, but are not limited to, language and cultural differences, which may impact the decision of whether to seek help (Du Mont & Forte, 2012; Sinha, 2013). Little research has examined domestic homicide within immigrant and refugee communities in Canada.

Children may be killed “in the crossfire of a violent altercation” or as an act of revenge against a spouse who leaves an abusive relationship (Jaffe & Juodis, 2006, p. 25; Jaffe, Campbell, Hamilton & Juodis, 2012). In Ontario alone, 29 child deaths occurred in the context of domestic violence between 2002 and 2010 (Office of the Chief Coroner for Ontario, 2015). Therefore, these four populations each experience specific factors that may explain their vulnerability to domestic homicide and challenges to reporting domestic violence and obtaining support. Assessing and managing these factors is crucial for preventing domestic violence and homicide, yet there is a paucity of research identifying these specific risks among these populations and how they might be addressed.

The Canadian Domestic Homicide Prevention Initiative with Vulnerable Populations (CDHPIVP) emerged to help address these noted gaps in research and practice. This Canada-wide initiative seeks to further our understanding of domestic homicide risk among the four vulnerable populations noted above in order to inform risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning. One of the initiative’s main objectives is to conduct cross-sectoral research on risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning to enhance our national capacity to reduce domestic violence and domestic homicide among vulnerable populations.

The present literature review is a first step in that process. The purpose is to systematically and critically review the national and international literature on risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning among the four vulnerable populations. This review provides a current and comprehensive assessment of the state of research and best practices as well as providing a foundation for future research by the CDHPIVP.

Related to these overlapping populations, the research questions we are seeking to answer are: (1) what are the specific risk factors among Indigenous populations; rural, remote, and northern populations; immigrant and refugee populations; and children exposed to domestic violence and homicide; and (2) what risk assessment, risk management, and/or safety planning strategies prevent domestic violence among Indigenous populations; rural, remote, and northern populations; immigrant and refugee populations; and children exposed to domestic violence and homicide?

Overview of Literature Review Report

We begin this literature review with a brief overview of international domestic homicide death review and prevalence, as well as current challenges collecting and sharing data on domestic homicides. We then explain the method for each phase of this systematic literature review, briefly review the theoretical frameworks that guided our analysis of the existing literature, and provide an overview of current domestic violence risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning definitions and research. Next, we provide a comprehensive review of the literature on vulnerabilities, risk assessment, risk management, safety planning, and future priorities for research and practice among the four vulnerable populations (Indigenous populations; rural, remote, and northern populations; immigrant and refugee populations; and children exposed to domestic violence). Finally, we discuss the findings of our literature review and argue for the need for differentiated, social, and intersectional approaches to domestic violence research and practice.

Domestic Homicide

Domestic homicide has been a research focus around the world, including systematic death reviews and inquiries. There are established death review committees in Canada, the U.S., New Zealand, Australia, and the U.K. (Bugeja, Dawson, McIntyre, & Walsh, 2015; Dawson, 2017). Countries around the world with death review committees provide expansive definitions of domestic homicide (Fairbairn, Jaffe, & Dawson, 2017). In Canada, domestic violence death review committees (DVDRCs) expand upon the understanding of domestic homicide as the most extreme form of domestic violence to include victims beyond intimate partners. In Ontario, for example, domestic homicide is defined as “all homicides that involve the death of a person, and/or his or her child(ren) committed by the person’s partner or ex-partner from an intimate relationship” (Office of the Chief Coroner for Ontario, 2015, p. 2).

Domestic homicide is a gendered crime. In Canada, the rate of domestic homicide is 4.5 times higher for female victims than for male victims (Beaupré, 2015). Between 2003 and 2013, police reported 960 intimate partner homicides, with 747 committed against a female victim, representing over 75% of intimate partner homicides (Beaupré, 2015). 76% of domestic homicides involve current or former married and common-law spouses (Beaupré, 2015). Across countries where homicide data are collected, more than one third of homicides of women are perpetrated by an intimate partner (Stöckl et al., 2013). Additionally, one in seven homicides is committed by an intimate partner, with the proportion of women killed by a partner being six times higher than the proportion of men killed by a partner (Stöckl et al., 2013). The gendered nature of these deaths has been reported in multiple countries, including Sweden and Denmark (Rying, 2001; Leth, 2009), England and Wales (Aldridge & Browne, 2003), Finland (Weizmann-Henelius, Matti Grönroos, Putkonen, Eronen, Lindberg, & Häkkänen-Nyholm, 2012), New Zealand and Australia (Family Violence Death Review Committee, 2014; New South Wales Domestic Violence Death Review Team, 2015), the U.S. (Cooper & Smith, 2012), and South Africa (Abrahams, Mathews, Martin, Lombard, & Jewkes, 2013). While much research has looked at prevalence rates and risk factors, less is known about how to best enhance risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning strategies, especially across diverse and vulnerable populations.

Research Challenges

There have been some noteworthy challenges regarding collecting and sharing data on domestic homicides. First, multiple professionals across different disciplines become involved once a homicide occurs, including police, coroners, pathologists, and crown attorneys. As a result, information regarding each case is not located in one specific place or system (New Brunswick DVDRC, 2012). Another concern when involving multiple professionals is the challenges that can occur in terms of communication. For example, when collecting information regarding the victim-offender relationship, information may be missing, partly due to the nature of homicide data and the poor links between police and coroner information, even when advanced homicide monitoring data systems are in place (Stöckl et al., 2013). Some victims may have been isolated and prior violence may have been hidden, which places a demand on police for more thorough interviews with friends, family, neighbours, and co-workers. These challenges further emphasize the importance of (a) establishing and maintaining domestic violence death review committees to ensure collaboration among different sectors when collecting and sharing homicide data as well as (b) developing more innovative research methods to address priority research questions.

Domestic violence victims and perpetrators are not a homogenous population: therefore, how this violence is experienced and prevented is shaped by various intersecting factors including geographical location, socio-economic status, racialization, colonialism, age, and immigration status, among other factors. As this literature review demonstrates, when looking specifically at risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning research in the context of domestic violence, it is important to consider the various intersecting factors. By identifying gaps and challenges in the existing literature, we can begin formulating a knowledge base that can support prevention efforts across diverse and marginalized populations.

The next chapter provides a description of the methodology for the literature review including the search strategy and analysis.

Literature Review Methodology

Authors: Nicole Jeffrey

Contributors: Jordan Fairbairn

This systematic review consisted of three phases: a literature search, annotated bibliographies, and a literature analysis. Two research questions guided this search: (1) what are the risk factors among Indigenous populations; rural, remote and northern populations; immigrant and refugee populations; and children exposed to domestic violence and homicide and (2) what risk assessment, risk management, and/or safety planning strategies prevent domestic violence among Indigenous populations; rural, remote, and northern populations; immigrant and refugee populations; and children exposed to domestic violence and homicide? The first research question was identified as important to understanding domestic violence. The second research question was developed using a PICOS framework (Higgins & Green, 2011); i.e., it specified the types of populations or participants being studied (P), the types of interventions (I), comparisons to other possible interventions (C), the types of outcomes that were of interest (O), and the study designs used to evaluate the effects of the interventions on those outcomes (S). The goal of the review was to synthesize research on risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning related to incidences of repeat or lethal domestic violence among Indigenous populations; rural, remote, and northern populations; immigrant and refugee populations; and children exposed to domestic violence.

Literature Search Strategy

The review was international in scope and included documents written in English and also dated between January 01, 2000 to December 31, 2015[1]. A wide range of academic and grey literature sources were included, such as journal articles, reports, conference papers, theses, and dissertations. We began by developing for each vulnerable population a comprehensive list of search term combinations that included different terms for the intervention, the outcome (i.e., violence), and the population (see Table 1). Research assistants entered each combination of search terms (e.g., prevent* AND “domestic homicide” AND child*) into the ProQuest and PubMed databases.

Table 1: Literature Search Terms

|

The Intervention |

The Outcome (i.e., violence) |

The Population |

|

prevent* |

“domestic homicide” |

Aboriginal |

|

intervention* |

“domestic violence” |

Indigenous |

|

tool* |

“child homicide” |

rural |

|

treatment* |

femicide |

remote |

|

risk* |

filicide |

northern |

|

Safety |

“intimate partner violence” |

immigrant* |

|

|

“murder-suicide” |

refugee* |

|

|

“spousal homicide” |

child* |

|

|

“family violence” |

|

|

|

uxoricide |

|

|

|

“wife assault” |

|

|

|

“wife battering” |

|

To identify relevant documents, research assistants screened all titles and abstracts for a focus on (a) domestic violence; (b) risk assessment, risk management, or safety planning strategies, or identification of risk or vulnerability factors, particularly for the four identified populations; and (c) one or more of the four vulnerable populations (though relevant articles not focused on these four populations were also included). Articles that met the above criteria were added to a shared EndNote[2] library. A total of 1,299 academic references were generated from this process: 187 in the Indigenous group; 215 in the rural, remote, and northern group; 266 in the immigrant and refugee group; 283 in the children exposed group; and 348 in the general population group.

This process was then repeated for grey literature databases including ProQuest Dissertation and Theses, OpenDOAR, and Google as well as targeted searches on agency websites such as Public Health Agency of Canada and Department of Justice Canada. The first 100 results from each search were selected for review. Grey literature retrieved primarily included conference papers, theses and dissertations, government and non-government reports, and handbooks. A total of 981 documents were generated: 168 in the Indigenous group; 254 in the rural, remote, and northern group; 168 in the immigrant and refugee group; 67 in the children exposed group; and 324 in the general population group. Thus, from thousands of articles scanned during the article searches, 2,280 were selected for further review and inclusion in the CDHPIVP EndNote library.

Next, the titles and abstracts of each document were re-read by members of the CDHPIVP literature review team and rated based on the extent to which they provided information on risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning and on characteristics or circumstances of one of the vulnerable populations. If no abstract was available, the document was scanned for relevance. Based on this process, 589 documents were selected for inclusion in the literature review. Table 2 presents the total references reviewed for the annotated bibliographies and full report.

Annotated Bibliographies

Next, members of the team read each document and completed a data form outlining key pieces of information found within each document, including research purpose, theoretical framework, methods, main findings, and any recommendations related to risk assessment, risk management, or safety planning. This information was used to write a summary for each document. The summaries were then compiled into several annotated bibliographies based on the population they pertained to (i.e., Indigenous; rural, remote, and northern; immigrant and refugee; children exposed; or general population). Overlapping articles were included in both relevant annotated bibliographies (e.g., Indigenous and rural, remote, and northern; immigrant and refugee and children).

Table 2: Reference Breakdown

|

Group |

Academic Literature |

Grey Literature |

Total |

|

General risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning |

31 |

25 |

56 |

|

Indigenous |

34 |

48 |

82 |

|

Immigrant and refugee |

117 |

81 |

198 |

|

Rural, remote, and northern |

76 |

58 |

134 |

|

Children |

93 |

26 |

119 |

|

TOTAL |

351 |

238 |

589 |

Literature Analysis

Team members then read and took notes about each document/article for the data collection sheet to summarize the focus and objective of each study, the theoretical approach and methods, the tools, scales or assessment instruments tested, the risk factors identified for the population, and the core findings or recommendations made pertaining to risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning. Following this process, four team members, including two project supervisors, imported these summaries into NVivo (a qualitative analysis software) to code and organize key findings according to: (1) risk assessment, (2) risk management, (3) safety planning, and (4) theoretical frameworks used. Each summary sheet was coded once, and researchers conferred regularly to address questions as they arose. Additionally, as the researchers coded for these core themes they identified additional emerging themes pertaining to barriers to service provision, protective strategies, risk factors, and recommendations for each vulnerable population. The information in each code was then used as a basis for writing up the vulnerable populations chapters.

Theoretical Frameworks

Authors: Nicole Jeffrey, Jordan Fairbairn, Myrna Dawson

Various frameworks are used to understand domestic violence and domestic homicide. In this section, we argue for the importance of the social ecological model for unpacking literature on risk factors, risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning for vulnerable populations; and we explain its use in this literature review. We also outline exposure both reduction and intersectionality as two theoretical lenses that guide the CDHPIVP’s focus on risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning and, in this regard, point to the need to move beyond general strategies to center vulnerable and marginalized populations.

Social Ecological Model

In recent decades, the social ecological model has emerged as a central way to understand gendered violence such as domestic and sexual violence. This model was originally developed by Bronfenbrenner (1979; 2005) to explain “how human beings grow and change in the context of multiple systems” (Nelson & Lund, 2017, p. 12). It was later adapted by others (e.g. Heise, 1998; Dahlberg & Krug, 2002) to lay out various levels of influence (ecologies) to understand complex phenomena such as violence against women (Heise, 1998). In the context of the prevention of violence against women, the social ecological model explores how risk factors occur at individual, relationship, community, and societal levels and targets prevention efforts accordingly (see Heise, 1998; Dahlberg & Krug, 2002).

Although the exact terminology and number of levels vary,[3] the social ecological model is founded on the principle that the origins and consequences of violence involve a combination of factors at multiple levels (Oetzel and Duran, 2004, p. 52). This framework is important because it recognizes the interconnectedness of various risk factors. Additionally, it allows us to integrate individual level theories (e.g. social learning theory) with societal-level theories such as feminist perspectives (Heise, 1998; Johnson & Dawson, 2011). This fills an important gap in the “either-or” approach to individual and societal explanations of violence. As Heise (1998, p. 262-263) explains, “Theorists have either tended to emphasize individual explanations for violence…or they propose social/political explanations…Only recently have theorists begun to concede that a complete understanding of gender abuse may require acknowledging factors operating on multiple levels”

This literature review explores research on domestic violence risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning with vulnerable populations. Because domestic violence has historically been considered a private event, most research has focused on individual level risk factors (Cunradi, 2010). However, in recent years there has been increased and widespread awareness that individual understandings and prevention strategies alone will not eliminate domestic violence. Increasingly, research and policy recognize that addressing domestic violence requires understanding and targeting various levels of prevention (see, for example, Alaggia, Regehr & Jenney, 2012). For example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDCP, 2017, para. 3) states that “A combination of individual, relational, community, and societal factors contribute to the risk of becoming an IPV [intimate partner violence] perpetrator or victim. Understanding these multilevel factors can help identify various opportunities for prevention.”

Table 1 Outlines select examples of risk factors at various levels (CDCP, 2017).

Table 1, Examples of risk factors at multiple levels

|

Level |

Risk factors |

|

Individual |

Prior history of being physically abusive; belief in strict gender roles |

|

Relationship |

Dominance and control within the relationship |

|

Community |

Weak community sanctions against domestic violence |

|

Societal |

Traditional gender norms |

Adapted from the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (2017)

Understanding multilevel factors may be additionally important in working with vulnerable and/or historically marginalized population. For example, Nelson and Lund (2017) explain that

Efforts to support women to safety and out of isolation will not be as effective unless practitioners carefully consider WWD’s [women with disabilities] entire ecological context as a person with a disability and the consequences of reciprocal interactions between these various systems. (p. 11)

Furthermore, as this literature review discusses, Indigenous communities are an example of a historically marginalized population where (a) a focus on individual and relationship level risk factors for domestic violence is insufficient and (b) an understanding of colonization and structural violence is imperative to working on risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning. Thus, the social ecological model can help to move past a focus on individual-level risk factors to understand how communities, families, and societies at-large feature in risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning.

Given the centrality of this framework in current research and practice, this literature review uses the social ecological model as the overarching framework to highlight the complex and multifaceted nature of domestic violence. This understanding is furthered by our use of the theoretical tools exposure reduction and intersectionality, discussed in further detail in the following sections. When understood in combination with the social ecological model, exposure reduction and intersectionality frameworks help emphasize that preventing domestic homicide requires (a) addressing risk factors for each population at multiple levels to reduce exposure to violent relationships and (b) developing risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning strategies at multiple levels that consider overlapping identities and intersecting axes of oppression.

Exposure Reduction Framework

Exposure reduction is a framework emphasizing that domestic homicide prevention requires the identification of mechanisms to support intimate partners in enabling them to reduce their risk of victimization. This may occur by helping them leave an abusive relationship, overcoming barriers that prevent them from protecting themselves in an effective manner, or addressing perpetrator attitudes and behaviours—including making them more accountable (Dawson, Bunge, & Balde, 2009; Dugan, Nagin, & Rosenfeld, 1999, 2001, 2003). This framework has been used to help explain recent declines in intimate partner homicides in the U.S. and Canada (Dawson et al., 2009; Dugan et al., 1999, 2001, 2003). The framework is based on the consistent finding that prior ongoing relationship violence is a major risk factor for intimate partner homicide (Browne, Williams, & Dutton, 1999; Campbell, 1992; Campbell et al., 2003; Gartner, Dawson, & Crawford, 1999; Goetting, 1995).

Thus, resources, policies, programs, and broader social changes that effectively help abused partners to leave an abusive relationship, to reduce their risk by effectively addressing the violence in a relationship, or to prevent these relationships from developing (i.e., exposure-reducing mechanisms) should reduce the rate of intimate partner homicide (Dawson et al., 2009; Dugan et al., 1999, 2001, 2003). Drawing from this framework, this literature review considers risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning strategies that aim to prevent domestic violence from occurring, with the understanding that ending exposure to domestic violence will reduce domestic homicide rates.

Supporting the exposure reduction framework, three broad social changes—and, hence, exposure-reducing indicators—have been linked to declines in intimate partner homicide rates: (1) increased gender equality, such as women’s increased income and educational attainment relative to men’s; (2) changes in the structure of intimate relationships, such as decreased marriage rates; and (3) changes associated with the domestic violence movement, such as increased domestic violence resources (e.g., legal services; Dawson et al., 2009; Dugan et al., 1999, 2003; Reckdenwald, 2008; Reckenwald & Parker, 2010; Rosenfeld, 1997). Each social change supports the idea that, as women become more independent and/or have more opportunities to leave or avoid violent relationships, the likelihood of their being killed by a partner or killing a partner in self-defense is reduced. These links, however, are not always straightforward and sometimes differ based on race/ethnicity, relationship type, and gender. For example, a study by Dugan et al. (2003) in the U.S. found that stronger arrest policies were related to fewer homicides of unmarried partners, but this association was driven largely by African-American victims. Many exposure-reducing mechanisms are also associated with reductions in the rate at which women kill their male partners but not the rate at which men kill their female partners (Dugan et al., 1999, 2003). Dugan et al. (1999, 2003) proposed that this is because women are more likely to kill their partners to protect themselves or their children, and many exposure-reducing mechanisms provide protective alternatives to violence and homicide.

Dugan et al. (1999, 2001, 2003) have also assessed the possibility that, under certain conditions, exposure reducing mechanisms may actually increase the likelihood of intimate partner homicide through a retaliation or backlash effect that might occur if some mechanism or intervention “angers or threatens the abusive partner without effectively reducing contact with the victim” (Dugan et al., 2003, p. 174). For instance, women’s increased economic and/or social status may threaten men’s control in intimate relationships and result in greater violence and homicide as men attempt to regain that control (Dugan et al., 2003; Reckdenwald, 2008). Indeed, Dugan et al. (1999) found that women’s improved economic status was associated with increased female intimate partner homicide victimization. Based on these findings, researchers have concluded that enhanced attention to both victim safety as well as risk management of the perpetrator may be critical in severely violent relationships (Dawson, 2010; Dugan et al., 2003). At the very least, this body of work demonstrates the “clear implications for victims who may not have sufficient access to resources and, as a result, lack one key mechanism for reducing their exposure to further violence” (Dawson, 2010, p. 12).

The exposure reduction framework has not yet been widely tested among diverse and vulnerable populations. However, Chin (2012) found that women’s participation in the labour force was associated with a significant reduction in physical spousal violence in India. Analyzing how economic factors interact with cultural factors, Chin argues that, in a patriarchal cultural setting, increasing financial resources for women without effective exposure reduction (e.g., actual labour force participation) might result in male backlash and negatively impact violence against women. With respect to rural populations, Taylor and Jasinski (2011) suggest that, because many services are located in urban areas, their exposure reducing effects may be less pronounced in rural areas. Thus, more work is needed to better understand the effects of exposure reduction in more diverse and vulnerable populations and how services can better reach these groups.

Intersectionality

Intersectionality (sometimes referred to as interlocking paradigm) is a framework that considers the multilayered dimensions of social identities and/or locations—including gender, race, ethnicity, class, age, ability, geographic location, Indigeneity, sexual orientation, and immigration status—and how they intersect to shape experience (Bograd, 1999; Brassard, Montminy, Bergeron, & Sosa-Sanchez, 2015; Crenshaw, 1989, 1991; Davis, 2008; Erez, Adelman, & Gregory, 2009; Mehrotra, 2010; Sandberg, 2013; Sokoloff, 2008a, 2008b). Despite differences in interpretation and application, many approaches to intersectionality consider the ways that hierarchies of power (and, thereby, oppression) exist along these dimensions (Bograd, 1999). Thus, individual experience (including privilege and oppression) is shaped through the interaction of multiple systems of power. These social locations shape lives in interacting and compounding ways that cannot be captured by looking at each dimension separately (Crenshaw, 1991). Thus, intersectionality moves beyond the traditional research approach of treating each dimension as independent by acknowledging “that the impact of intersecting identities is qualitatively different from the impact of any single identity or the addition of them” (Dill & Zambrana, 2009; Etherington & Baker, 2016, p. 3).

Intersectionality can and has informed theory, research, and practice related to several social issues including domestic violence (Bograd, 1999; Cramer & Plummer, 2009; Etherington & Baker, 2016; Kelly, 2011; Sokoloff, 2008a, 2008b). An intersectional framework challenges the traditional primacy of gendered analyses of domestic violence and promotes an examination of how other social locations may intersect with gender to shape women’s experiences of violence (Crenshaw, 1991; Sokoloff & Dupont, 2005). While extremely useful for facilitating a feminist movement against domestic violence, the traditional approach has been dominated by the voices and experiences of White, middle-class women (Richie, 2000; Sokoloff & Dupont, 2005). Intersectional approaches, in contrast, have been crucial for legitimating the experiences of marginalized women from diverse social locations (Crenshaw, 1991; Sokoloff, 2008; Sokoloff & Dupont, 2005). These approaches have also helped explain the complexity of differences in racial and cultural domestic violence prevalence rates. For instance, the importance of socioeconomic status has been highlighted as a central structural factor related to the higher domestic violence prevalence rates among some groups (e.g., Black and immigrant women; Adams & Campbell, 2012; Sokoloff & Dupont, 2005).

An intersectional approach is essential for both understanding and addressing domestic violence among diverse populations—or example, (a) the intersection of various social locations can influence how domestic violence is experienced and interpreted by women and responded to by others; (b) the barriers that exist to obtaining support and safety; (c) the personal and social consequences of domestic violence; and (d) how interventions functions (Adams & Campbell, 2012; Bograd, 1999; Brassard et al., 2015; Sandberg, 2013; Sokoloff, 2008a, 2008b). Thus, intersectionality providing a more nuanced understanding of the needs and experiences of diverse populations can, in turn, assist in the creation of more relevant, effective, and culturally-sensitive services and policies. Indeed, strategies that are developed based on the experiences of a homogenous group of women or that do not consider how additional axes of oppression shape some women’s lives will be less fruitful for (and potentially harmful to) some groups of women (Crenshaw, 1991; Sokoloff & Dupont, 2005). This may be particularly important in the areas of risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning.

To date, an intersectional approach has been used in domestic violence research and theory development with all of the vulnerable populations of interest in this report including immigrant woman (e.g., Adams & Campbell, 2012; Erez et al, 2009; Sokoloff, 2008; Sokoloff & Pearce, 2011), Indigenous women (e.g., Brassard et al., 2015; Centre de recherché interdisciplinaire sur la violence familiale et la violence faite aux femmes, 2011), and, to a lesser extent, children exposed to domestic violence (e.g., Etherington & Baker, 2016) and women living in rural and remote locations (e.g., Sandberg, 2013). As one example, research finds that intersecting social locations such as gender, ethnicity, and legal status contribute to immigrant women’s domestic violence experiences and barriers to help-seeking. This includes limited access to social service or criminal justice services, legal dependency on their abusers, fear of losing the support of their immigrant communities, isolation, and fear of deportation (Adams & Campbell, 2012; Erez et al., 2009).

Overview of Risk Assessment, Risk Management, and Safety Planning

Authors: Nicole Jeffrey

Contributors: N.Zoe Hilton, Randy Kropp, Marcie Campbell, Jordan Fairbairn

Risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning are key processes in the prevention of domestic violence and homicide. This chapter refers to literature in the field to provide a brief overview of risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning; however, this chapter is meant to provide information and context and was not part of the literature review.

Risk Assessment

Although there is little consensus in the literature with respect to defining risk, most define it in terms of a victim’s likelihood of experiencing or a perpetrator’s likelihood of perpetrating future domestic violence (DV) or homicide (Belfrage, Strand, Storey, Gibas, Kropp, & Hart, 2012b; Campbell et al., 2004; Campbell, Webster, & Glass, 2009; Eke, Hilton, Harris, Rice, & Houghton, 2011; Hilton & Harris, 2009; Hilton, Harris, Rice, Houghton, & Eke, 2008; Hilton et al., 2004; Messing, Campbell, Webster, Brown, Patchell, & Wilson, 2015; Nicholls, Pritchard, Reeves, & Hilterman, 2013). The CDHPIVP defines risk assessment as “evaluating the level of risk of harm a victim (or others connected to the victim) may be facing including the likelihood of repeated violence or lethal (dangerous) violence, based on a professional’s judgment and/or a structured interview and/or a tool (instrument) that may include a checklist of risk factors” (Campbell, Hilton, Kropp, Dawson, & Jaffe, 2016, p. 3). Risk assessment may be carried out by professionals working in different human services. Some of these service providers may be specialists in the domestic violence field (such as police officers and shelter workers); other professionals may be drawn into these issues on an occasional basis, e.g., in workplaces and post-secondary settings (such as mental health professionals, nurses, doctors, corrections staff, and human resources and security personnel). Professionals should strive to determine the most appropriate intervention to manage and mitigate the risk (Kropp, 2008; Nicholls et al., 2013). Thus, the goal of risk assessment is to inform risk management and safety planning to prevent future violence.

There are three main approaches to risk assessment: (1) unstructured clinical decision making, (2) the actuarial approach, and (3) structured professional judgment. In the first approach, professionals in the DV field assess risk more informally, without guidelines, using their own judgment and experience in the field (Campbell et al., 2016; Kropp, 2008; Nicholls et al., 2013). This approach is beneficial in that it can be tailored to each individual case. However, the subjective nature of this approach means it may miss important sources of information and risk factors identified in the literature that could otherwise be used to inform appropriate and effective interventions (Campbell et al., 2016; Kropp, 2004, 2008). Personal preferences, biases, and specialized trainings might also mean that empirically studied and widely accepted risk factors and intervention strategies are disregarded or overlooked (Campbell et al., 2016). Because of this challenge, many in the field are moving away from unstructured clinical decision making and are using more structured approaches to risk assessment (Dutton & Kropp, 2000; Kropp, 2008; Hilton & Harris, 2005).

Secondly, actuarial approaches to risk assessment use a tool containing empirically-derived risk factors, which are combined and interpreted using statistical models to estimate a perpetrator’s risk of (re)offending. Actuarial tools compare an individual perpetrator’s risk to that of other known perpetrators and provide an estimate of the probability of reoffending (Campbell et al., 2016; Nicholls et al., 2013). Two common actuarial risk assessment tools identified in the literature are the Ontario Domestic Assault Risk Assessment Guide (ODARA; Messing & Thaller, 2013; Hilton & Harris, 2009; Hilton et al., 2004) and the Domestic Violence Risk Appraisal Guide (DVRAG; Hilton et al., 2008). Actuarial approaches have greater reliability than unstructured clinical decision making (Grove & Meehl, 1996; Nicholls, Desmarais, Douglas, & Kropp, 2002) and predict violent recidivism with greater accuracy than unstructured risk assessment and structured professional judgment tools (Hilton & Harris, 2005). Actuarial approaches fit within the Risk Need Responsivity (RNR) framework. The RNR framework states that (a) perpetrator recidivism can be reduced if the level of treatment provided is proportional to the perpetrator’s risk to re-offend (risk principle); (b) treatment should focus on dynamic risk factors directly linked to the perpetrator’s violent behaviour (e.g., substance abuse; family/marital relationships; employment) (need principle); and (c) treatment should be about engaging the perpetrator and providing evidence-based interventions that reduce violent/criminal behaviour and tailoring interventions to enhance the perpetrator’s strengths while accommodating for certain barriers (e.g., learning disabilities, motivation, mental health) (responsivity principle) (Bonta & Andrews, 2007; Canales et al., 2013). Within this framework, actuarial approaches can suggest an overall level of risk management that might be needed; however, they do not inform specific management or prevention strategies or allow consideration of contextual or case-specific factors (Douglas & Kropp, 2002; Kropp, 2004).

Finally, the structured professional judgment approach assesses risk using guidelines that reflect theoretical, clinical, and empirical knowledge about DV (Douglas & Kropp, 2002; Kropp, 2004). Common structured professional judgment risk assessment tools include the Spousal Assault Risk Assessment – Version 3 (SARA–V3; Kropp & Hart, 2015; Dutton & Kropp, 2000; Kropp & Hart, 2000; Kropp, Hart, Webster, & Eaves, 1994; Messing & Thaller, 2013) and the Danger Assessment* (DA; Campbell et al., 2009; Dutton & Kropp, 2000; Messing & Thaller, 2013). This approach offers a middle ground between unstructured clinical decision making and the actuarial approach. It is structured in that it provides professionals with guidelines for risk factors, information gathering, and risk management strategies; yet it is flexible and practical in that it allows some professional discretion in determining risk (Campbell et al., 2016; Douglas & Kropp, 2002; Kropp, 2008; Kropp & Hart, 2015). The flexibility of the structured professional judgment approach allows for the inclusion of case-specific factors as well as women’s own perceptions of risk, which can enhance prediction (Heckert & Gondolf, 2004; Stansfield & Williams, 2014; Weisz, Tolman, & Saunders, 2000). However, this flexibility also makes this approach more subjective as the level of risk is based on the professional’s discretion, the qualifications of the professional, and the information provided for the assessment (Helmus & Bourgon, 2011). Some professionals feel uncomfortable with the amount of subjectivity needed to assess risk using the structured professional judgment approach (Canales et al., 2013). Therefore, it is important when using the structured professional judgment approach that the professionals are trained and qualified and that multiple sources of information are used (Helmus & Bourgon, 2011; Kropp & Hart, 2000).

Research evaluating and comparing the various DV risk assessment tools is still in its early stages with “considerable methodological limitations hampering the clinical implications that can be drawn” (Nicholls et al., 2013, p. 148). For example, little research has compared multiple risk assessment measures, used prospective or longitudinal designs, or included victims and collaterals to measure recidivism. Nevertheless, research has tended to find modest predictive validity among the various tools (for reviews see Messing & Thaller, 2013; Nicholls et al., 2013; and Helmus & Bourgon, 2011). Although predictive validity is an important test of efficacy since it measures a tool’s ability to correctly predict future (re)assault, other factors must also be considered when choosing which risk assessment instrument to use (e.g., setting, outcome, skills of the assessor, access to information, cultural appropriateness, or usefulness for risk management; Kropp & Hart, 2015; Messing & Thaller, 2013).

Literature in the field proposes several recommendations around the use of DV risk assessment, four of which are discussed here. First, a structured, reliable, and validated tool or guideline should be used when conducting risk assessments; however, if it is not possible to use an established tool or method then the risk assessment should at least consider empirically or professionally supported risk factors (Campbell, et al., 2016). Second, risk assessment should use multiple methods and sources of information such as interviews with the perpetrator, victim(s), and other informants. This might include family and friends, criminal records, and mental health reports. However, assessments should not consider discriminatory information such as race, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status (Campbell et al., 2016; Dutton & Kropp, 2000; Kropp, 2008; Kropp & Hart, 2015). Third, professionals who conduct risk assessments should receive appropriate and adequate training and education on the use of tools or guidelines (Campbell et al., 2016; Kropp, 2008). Finally, while risk assessment can provide information on the nature, degree, and likelihood of risk, it cannot cover all risk factors and circumstances and, therefore, “should not be used to marginalize or minimize the concerns of those victims believed to be at lower risk” (Kropp, 2004, p. 677). It is also important to incorporate the victim’s perspective into an assessment; however, this information is sensitive and should never be shared with the perpetrator to ensure the victim’s safety (Campbell et al., 2016).

Johnson (2010) argues that risk assessment tools can infringe on women’s dignity and autonomy and urges risk assessment administrators to (1) be transparent regarding the objectives, means, and advantages and disadvantages of lethality assessments; (2) obtain informed consent before conducting assessments and permit women to decline; and (3) engage in woman-centered counselling to determine whether and how women want to use the tools and address the violence. Most importantly, risk assessment must not be considered an end in itself; it is part of a process aimed at preventing domestic violence (Campbell et al., 2016; Dutton & Kropp, 2000; Kropp, 2008; Yang, Wong, & Coid, 2010). As such, it should inform risk management and safety planning.

Risk Management

The CDHPIVP defines risk management as strategies intended to reduce the risk presented by a perpetrator of domestic violence (Campbell et al., 2016) and can include treatment, monitoring, or supervision[4] (Campbell et al., 2016; Juodis, Starzomski, Porter, & Woodworth, 2014; Kropp, 2008). Treatment involves the provision of rehabilitative services including violence interventions (e.g., batterer intervention programs; Babcock, Green, & Robie, 2004; Augusta-Scott, Scott, & Tutty, 2017), mental health and addictions treatment (e.g., individual or group psychotherapy), and training programs to improve interpersonal and anger management skills (Juodis et al., 2014; Kropp, 2008). Monitoring involves surveillance or repeated risk assessment so that management strategies can be adapted (Kropp, 2008). Strategies for monitoring include contacts with the perpetrator and other relevant people, field visits, electronic surveillance, and drug testing. Finally, supervision involves restrictions of the perpetrator’s liberties, such as restricting activities (e.g., curfews, weapons prohibitions) and communications (e.g., with (ex)partner or children) or involuntary incarceration (Juodis et al., 2014; Kropp, 2008). Incarceration is often recommended for high-risk perpetrators (Juodis et al., 2014; Kropp, 2008).

Risk management is often associated with the justice system, but many professionals who are in contact with perpetrators have an opportunity to conduct risk management. For example, general practitioners may be particularly well positioned to engage in risk management strategies, such as making referrals to men’s intervention programs (Hegarty, Forsdike-Young, Tarzia, Schweitzer, & Vlais, 2016). Moreover, risk management should ideally involve cooperation “among a number of different professionals working in different agencies, each with a different skill set and mandate” (Kropp, 2008, p. 214). High-risk management teams are one such approach. For example, Domestic Violence Interagency Case Assessment Teams (ICATs) in British Columbia and Multi-Agency Risk Assessment Conferences (MARACs) in the U.K. are examples of multi-agency (e.g., police, victim services, or child welfare) teams who share information to identify, monitor, and manage high-risk domestic violence cases (Ending Violence Association of BC, 2015; Robinson & Tregidga, 2007). Ultimately, their goal is to develop risk management strategies and increase victim safety (Ending Violence Association of BC, 2015; Robinson & Tregidga, 2007).

Risk management teams often meet regularly and consider the needs of both victim and perpetrator in developing their action plans (Jaffe, Dawson, & Campbell, 2011; Robinson & Tregidga, 2007). Preliminary research has confirmed the benefits of multi-agency approaches, including victims’ feelings of support and reduced violence (Robinson & Tregidga, 2007). While considered a best practice in DV risk management, high-risk management teams are not without challenge (Jaffe, Dawson, & Campbell, 2011). For example, there can be issues associated with (a) collaboration among organizations with different (and sometimes competing) mandates, values, and interests and (b) confidentiality when sharing information between organizations (Jaffe, Dawson, & Campbell, 2011).

As indicated above, risk management can and should be informed by risk assessment. For example, risk management strategies can be aimed at specific risk factors and high-risk individuals can be targeted for more intensive risk management strategies (Dutton & Kropp, 2000; Hilton & Harris, 2005; Kropp & Hart, 2015; Yang et al., 2010). The structured professional judgment risk assessment approach offers a very clear link between DV risk factors and specific management strategies, and it allows for identification of perpetrators’ level of risk (Douglas & Kropp, 2002). Douglas and Kropp (2002) offer a useful overview of risk management strategies that correspond to various risk factors. For example, incarceration, intensive supervision, and violence treatment might be used among perpetrators with past violent behaviour, and crisis counselling, hospitalization, and weapons restriction might be used among perpetrators with recent suicidal or homicidal ideation or intent. Although a few studies link risk assessment and management (see Belfrage et al., 2012b), more research on how DV risk assessment can inform risk management is needed, especially given that effective risk management should target causal risk factors (Kropp, 2008; Yang et al., 2010).

Safety Planning

The CDHPIVP defines safety planning as any strategy to protect both DV victims and those around them (Campbell et al., 2016) and further recommends this be considered one of the highest priorities among professionals working with domestic violence victims and perpetrators (Horton et al., 2014). A “crisis-oriented approach that focuses attention on immediate safety needs,” (Lindhorst, Macy, & Nurius, 2005, p. 331-332)it often involves: (a) providing informational documents to victims, including contact information for local resources; and (b) educating victims regarding specific safety strategies, generally centered around having plans for immediate escape in case of actual or threatened violence at home, in the workplace, or other locations where perpetrators can access victims (Campbell, 2001; Goodkind, Sullivan, & Bybee, 2004; Kress, Adamson, Paylo, DeMarco, & Bradley, 2012; Murray et al., 2015). Some examples of strategies include: (a) having clothing, car keys, and important documents gathered and hidden in case the victim needs to leave quickly; (b) removing weapons from the home; (c) creating an escape plan; and (d) discussing the safety plan with a friend or family member (see Murray et al., 2015 for a review). Safety plans are predominantly developed with victims by social service providers (e.g., violence against women advocates, social workers, and counsellors); others, such as primary care physicians, can also help develop safety plans (especially in rural areas; McCall-Hosenfeld, Weisman, Perry, Hillemeier, & Chuang, 2015). Web- and computer-based safety decision aids are also beginning to emerge (Glass, Eden, Bloom, & Perrin, 2010; Koziol-McLain et al., 2015). These automated tools guide women through risk assessment, help them consider safety-related priorities (e.g., child’s well-being, having resources, maintaining privacy, or feelings for partner), and develop tailored safety plans (Bloom et al., 2014). These cost-effective tools can be used in diverse settings, including welfare offices, community agencies, libraries, and women’s own homes when safe and convenient (Glass et al., 2010; Koziol-McLain et al., 2015). One study found that women who used an online safety decision aid felt less decisional conflict and more supported about their safety than women who engaged in the usual safety planning for domestic violence (Eden et al., 2015).

Safety planning is based on the principles of empowerment and autonomy (Campbell, 2001; Campbell et al., 2016). As such, safety planning discussions should be collaborative, ongoing, and contextualized (Campbell et al., 2016; Horton et al., 2014; Lindhorst et al., 2005; Murray & Graves, 2012). A contextualized approach considers and respects women’s choices, perceptions, and situations—including their risk and protective factors, available resources, children, and the trade-offs of different safety strategies—and works with women to develop safety strategies (Campbell, 2001; Lindhorst et al., 2005; Thomas, Goodman, & Putnins, 2015). However, in situations where there is an imminent risk of harm or lethality, the overall safety of the victim and children may take precedence over ensuring the victim has choices and autonomy when developing a safety plan.

Although empirical research on formal safety planning is limited (e.g., Eden et al., 2015; Glass et al., 2010; Goodkind, Sullivan, & Bybee, 2004; Horton et al., 2014; Koziol-McLain, 2015; Kress et al., 2012; Messing, O’Sullivan, Cavanaugh, Webster, & Campbell., 2016; Murray et al., 2015; Thomas et al., 2015). However, studies examining the effectiveness of women’s use of various protective strategies may provide insight. For example, certain formal help-seeking strategies (such as staying in a shelter) appear to improve women’s safety and reduce abuse (Goodkind et al., 2004; Messing et al., 2016). In contrast, fighting back physically and obtaining defensive or security devices (e.g., mace or locks) appear to make the situation worse for many women and may even increase abuse or stalking (Goodkind et al., 2004; Messing et al., 2016). That is, fighting back physically might anger an abuser, and security devices may not deter stalking because stalking can occur from a distance (Goodkind et al., 2004; Messing et al., 2016). This body of work generally supports the importance of DV services and shelters (Goodkind et al., 2004).

This broad risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning literature review provides an overview of various tools and processes for reducing risk for domestic violence and homicide. Despite this important work, individual experiences of risk for domestic homicide are impacted by diverse factors such as racialization, experiences of colonial violence, immigration status, age, and geographical location. As such, the next sections of this literature review consider existing work on risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning specific to the four vulnerable groups: Indigenous populations; children; rural, remote, and northern populations; and immigrants and refugees.

Risk Assessment, Risk Management, and Safety Planning with Vulnerable Populations

The next four chapters provide a summary of the literature on domestic violence risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning with the four vulnerable populations that are the focus of this review. It is important to note that the introductions of each chapter include literature that was not identified in the review to provide an overall context. The literature from the review is summarized and discussed in the key findings and the priorities for research, practice, and policy development.

Indigenous Population

Authors: Olivia Peters, Jane Ursel, Claudette Dumont-Smith

Contributors: Josie Nepinak, Anna-Lee Straatman, Jordan Fairbairn

The term Indigenous[5] is defined by CDHPIVP as an inclusive term to encompass all Indigenous peoples and identities—including status, non-status, Indian, Aboriginal, Native, First Nation, Métis, and Inuit—who live on- or off-reserve. Historically, Indigenous peoples have been subject to colonization, Indian Residential Schools, and massive child apprehensions known as the sixties scoop. As a result of this history of abuse and forced assimilation, Indigenous people across Canada have been marginalized and deeply disadvantaged. One consequence of this history of repeated trauma to Indigenous families and communities is the overrepresentation of Indigenous people as victims of violent crime.

The 2014 General Social Survey (GSS) on Victimization reports that the overall rate of violent victimization for Indigenous people is more than double that of non-Indigenous people (163 per 1,000 versus 74 per 1,000). Indigenous people are more than twice as likely (9%) to report being victims of domestic violence than non-Indigenous people (4%). Indigenous women are especially vulnerable. According to Boyce (2016), their rate of violent victimization (220 per 1,000 people) has been double that of Indigenous men (110 per 1,000), almost triple that of non-Indigenous women (81 per 1,000), and more than triple that of non-Indigenous males (66 per 1,000), (Boyce, 2016). Statistics Canada consistently indicates the overrepresentation of Indigenous women and girls as victims of physical assault, sexual assault, and non-spousal homicide. They are more likely to experience violence or sexual victimization, and they are more likely to be killed by a stranger than non-Indigenous women (Lant, 2014; Native Women’s Association of Canada [NWAC], 2010; Royal Canadian Mounted Police [RCMP], 2015). A destructive stereotype of violence and Indigenous women is the narrative of Indigenous women living high-risk lifestyles. This narrative serves to normalize the violence, blame the victim, and must be deconstructed (Assembly of First Nations, 2013). Indigenous women are often at-risk not because they choose to take risks but because poverty and inadequate services put them at-risk (Federal-Provincial-Territorial Ministers Responsible for Justice and Public Safety, 2016). For example, the infamous “highway of tears,” the only highway between Prince George and Prince Rupert, has no public transport. Between 1969 and 2011 there are 16 known Indigenous murder victims and potentially 40 missing women who are likely victims on this deadly stretch of highway. Similarly, poverty and discrimination result in Indigenous people living in neighbourhoods that are often not safe. Simple daily activity like walking to a bus stop exposes women to risks. They do not choose a lifestyle that is risky; poverty imposes risks.

Statistics and circumstances such as these contribute to the recognition of Indigenous peoples as a particularly marginalized population. As such, part of this project is to map out existing research on preventing domestic homicide and that focuses on Indigenous populations. As this section will highlight, current research on Canadian Indigenous populations and domestic violence tends to focus on risk assessments rather than risk management and safety planning, thus reflecting a paucity of research in these areas.

Recognizing the multiple types of violent victimization that Indigenous people face in Canada, this initiative focuses on violence within the context of current or past domestic relationships. This is not to diminish or minimize the importance of non-domestic violence and homicide perpetrated by non-Indigenous perpetrators against Indigenous women. Rather, the CDHPIVP aims to address a related part of the larger problem of violence against Indigenous people seen both in Canada and around the world. This study deals specifically with risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning strategies for domestic violence and domestic homicide in Indigenous populations.

Indigenous peoples are vastly overrepresented in homicide statistics. Rates of homicide for Indigenous women have remained stable from the year 1980 to 2014 while rates for non-Indigenous women have declined (Miladinovic & Mulligan, 2015). A higher proportion of Indigenous than non-Indigenous people have been killed by someone they know, including intimate partners and other family members (Miladinovic & Mulligan, 2015).

Unique historical circumstances have played a central role in current issues around domestic violence and Indigenous peoples (see subsequent section “Historical Context”). Indigenous populations are more likely to experience concurrent risk factors such as substance abuse, poverty, and a history of physical or sexual abuse (Bottos, 2007). As well, there is a lack of Indigenous-specific supports, Indigenous community resources, and effective alternatives to mainstream justice responses. The preponderance of risk factors among Indigenous people are typically met with mainstream responses considered inappropriate for the needs of their families and communities (Cripps, 2007; Bopp, Bopp & Lane, 2003; Brown & Languedoc, 2004).

The “cultural appropriateness” of responses is a widely-contested topic requiring further examination because it seems to imply a homogeneity among Indigenous communities which are, in fact, much more likely to vary substantially in their needs and in their capacities (NWAC, 2011). There are considerable cultural differences and distinctions both between and within Indigenous communities across Canada. Acknowledging these differences, Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers, service providers, and other professionals explain that responses to domestic homicide should be specific to the communities in which they work. The uniqueness of and within Indigenous populations requires service responses based on local knowledge and sensitivity to community dynamics.

Acknowledging the statistics and concerns noted above, the literature reviewed calls for more attention and resources for marginalized Indigenous populations across Canada. The CDHPIVP seeks to address these issues and bring Indigenous populations to the forefront of homicide prevention research. Our objectives are to identify what risk assessment, risk management, and/or safety planning strategies might prevent domestic violence in Indigenous communities with attention to the unique historical context and current circumstances of Canadian Indigenous populations.

Indigenous peoples face many unique factors and additional challenges when examining the issue of domestic violence and abuse. Prior to contact, Indigenous peoples had their own governance models, and these varied by nation, spirituality, and cultural beliefs and practices. Through colonialism, Indigenous peoples were forced to accept foreign religious practices and beliefs, governance styles based on a patriarchal system, and laws that were imposed on them. Indigenous peoples, who had been self-governing for hundreds of years, were made ‘wards’ of the government through these colonial actions.

The Indian Act of 1876 (Indian Act, R.S.C., 1985, c. I-5) is specifically a colonial policy that has had a negative impact and continues to discriminate and oppress First Nations. The establishment of Indian Residential Schools, which were disastrous and destructive for Indigenous peoples, ensued from the powers vested under the Indian Act. The primary purpose of these institutions was to assimilate Indigenous peoples within the mainstream population. Records indicate that 150,000 Indigenous children—First Nations, Inuit, and Metis—as young as five were forcibly removed from their parents and communities and forced to attend these state and church-run schools. These schools operated from the mid-1800s, with the last Indian Residential School closing in 1996 (Schwartz, 2015). Former Prime Minister Paul Martin and Supreme Court Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin have described the Indian Residential School experience as “cultural genocide.” Genocide—defined as an attempt to destroy a people, in whole or in part—is a crime under international law (Fine, 2015).

Numerous reports and national studies describe the sexual, physical, emotional, mental, spiritual, and cultural abuses that were inflicted on a great number of Indigenous children attending these schools. Sadly, for some children this went on for years; and, in many instances, multiple generations of a family attended Indian Residential Schools and were victims of various forms of abuse. These traumatic experiences, when left untreated, were and continue to be passed on intergenerationally (Grau & Smith, 2011). Unresolved trauma can manifest itself in destructive behaviours to self, the family, and the community and can result in depression, anxiety, addictions, family violence, and suicidal and homicidal thoughts (Bohn, 2003; Moffitt et al., 2013).

Furthermore, First Nations women were especially affected by the Indian Act. Their “Indian” status was removed upon marrying a non-Indigenous person, unlike their male counterparts whose non-Indigenous spouses gained status upon marriage. This policy made First Nations women subordinate to First Nations men. In 1985 some changes to the Indian Act were legislated to enable First Nations women to re-gain their “Indian” status. However, their offspring have yet to attain equality to that of the descendants of First Nations men; thus, they are still regarded as inferior to their male counterparts.

Indigenous populations have had a long and complicated history of oppression, prejudice, and colonization in North America (Bohn, 2003). In Canada, this history can be traced back to the Indian Act of 1876 that took effect soon after Canada became an independent country in 1867. Through the Indian Act, the traditional ways and practices of Indigenous people and their languages, family and community networks, ceremonies, and territories were taken, destroyed and/or outlawed. The effects are still seen today.

Key Findings for Risk Assessment with Indigenous Peoples

Risk Factors. Statistics indicate that Indigenous peoples live in conditions well below the Canadian average. Many Indigenous peoples, because of their location, (a) live in poverty due to the absence of economic opportunities and the high cost of living; (b) live in sub-standard and over-crowded housing; and (c) have limited social and health supports and services (Moffitt, Mauricio, Marshirette & Mackenzie, 2013). Indigenous peoples, regardless of where they live, are subject to racism and discrimination in the social, health, and justice systems and have limited or no access to culturally-specific and culturally-safe health and social services (Wells, Strafford & Goulet, 2011). Further, Indigenous people are hesitant to access mainstream services because of stereotyping and racism. The barriers experienced by Indigenous peoples are further compounded by residence in rural, remote, and northern communities. Residents in these communities face geographic and transportation barriers to accessing necessary services for a wide range of needs including medical care, police response, addictions, and mental health services.

The negative impacts of colonization and the outdated discriminatory policies that are still in place continue to negatively impact the lives of Indigenous peoples. Rates of stranger violence, domestic violence, self-harm, and substance abuse are higher in the Indigenous population in comparison to the mainstream.

The literature suggests that, as a result of high levels of victimization, it is crucial to restore missing elements of Indigenous culture to address the problem of domestic violence (Blagg, Bluett-Boyd, & Williams, 2015; Brownridge, 2003). Furthermore, strategies to address domestic violence should be holistic in nature and consider the victim’s family and community. A factor that is unique to Indigenous populations concerning domestic violence is the idea of “community dimension” (Bopp et al., 2003). According to Bopp et al. (2003), mainstream responses to domestic violence often emphasize the individual or a specific family rather than the whole community. These authors note that it is important to consider the role of the community in domestic violence research and interventions, and to recognize that Indigenous communities cannot be approached with mainstream models of service. With this in mind, strategies to address domestic violence must be community-specific and developed with local knowledge and an understanding of community dynamics (Bopp et al., 2003).

Comparatively, Indigenous women are at a greater risk of experiencing domestic violence than non-Indigenous women. Indigenous women are more likely to experience violence of all severity levels, with an even greater likelihood of experiencing the more severe forms of violence (Brownridge, 2003; Nicholls, 2008). Brownridge (2008) found that colonization plays a large role in Indigenous women’s elevated risk of experiencing violence. Typically, risk factors do not account for this elevated risk (Brownridge, 2008). Thus, risk of victimization for Indigenous women is increased due to colonization, displacement, and loss of identity and traditional culture (Grau & Smith, 2011).

Factors that are associated with increased risk of violence for Indigenous peoples are poverty, young age, geographic isolation, living common-law, unemployment, low educational attainment, and substance abuse (Brassard et al., 2015; Brownridge, 2003; Burkhardt, 2004; Daoud, Smylie, Urquia, Allan & O’Campo, 2013; Jones, Masters, Griffiths, & Moulday, 2002). In addition, intergenerational trauma resulting from the Indian Residential School experience also places Indigenous peoples at an increased risk for domestic violence. This trauma, when untreated, is passed on from generation to generation and results in destructive behaviour within the family and community (Brownridge, 2003).

Risk Assessment Tools. The importance of using risk assessment instruments that are culturally-informed (designed with Indigenous populations and communities in mind) is found throughout the risk assessment literature. Specifically, risk assessments used with Indigenous populations should not be standardized intervention tools. These tools often neglect the specific needs of Indigenous communities, the role of Canada’s colonial history, and the importance of cultural and community values such as non-verbal communication strategies and Indigenous identity (Amellal, 2005; Buchanan, 2009). The diversity within and between Indigenous communities is not captured in mainstream risk assessment tools. Instead, research indicates that using holistic traditional practices that address and treat anger management, loss of identity, and experiences of trauma and abuse are effective practices among Indigenous populations (Amellal, 2005; Riggs, 2015; Victorian Indigenous Family Violence Task Force, 2003).

Several standardized risk assessment tools are currently used and are discussed in general risk assessment literature. These include, but are not limited to, the Spousal Assault Risk Assessment Guide (SARA), the Ontario Domestic Assault Risk Assessment (ODARA), the Aid for Safety Assessment Planning (ASAP), and the Physical Aggression Couples Therapy (PACT) tool (Al-Yaman, Doeland, & Wallis, 2006; Cairns & Hoffart, 2009; Riel, 2013). In general, these instruments tend to be more generic and are not developed specifically for use with Indigenous populations. For example, Buchanan (2009) found that the predictive accuracy of the Ontario Domestic Assault Risk Assessment (ODARA) and DVSI-R is comparatively weak with Indigenous populations, likely due to a lack of culturally-specific risk factors.

In discussing risk, we must acknowledge the diversity within and between Indigenous communities. For example, while the Danger Assessment has been applied to Indigenous women, Cairns and Hoffart (2009) recommend that the Indigenous women would benefit from an approach to risk assessment that considers the diversity within Indigenous populations. Very few risk assessment tools have been developed for Indigenous peoples; however, those that do exist are often specific to the community. For example, in Alberta a risk assessment has been developed called the Walking the Path Together POP TARTS tool: Protection, Options, Planning: Taking Action Related to Safety (The Alberta Council of Women’s Shelters, 2012). This tool, developed specifically for women living on-reserve, is an alternative to standard safety planning available on-reserve. It provides guidelines for assessing risk, helps women and their children to recognize dangerous situations and behaviour, and encourages women to trust their own feelings, body sensations, and intuitions (The Alberta Council of Women’s Shelters, 2012).

Another example of a resource that may be used when assessing risk with Indigenous peoples is a resource cited in Pimatisiwin (Chase, Mignone & Diffey, 2010) called the Life Story Board. Originally developed for children living in war zones, the Life Story Board allows an individual to create a visual representation of their story in a variety of contexts including violence. Chase, Mignone, and Diffey (2010) explain that the Life Story Board may be useful when assessing the risk of domestic violence, not only for adults but also for children and youth of diverse cultures. To consider the applicability of the Life Story Board within Indigenous communities, the authors conducted research with an Aboriginal Focus Program for social work students and asked Indigenous students to reflect on how the Life Story Board could be used. Responses included: (1) the impact of residential school experiences, (2) experiences with violence and loss, and (3) individual’s sources of strength (Chase et al., 2010). As many Indigenous cultures are characterized by traditions of storytelling, the Life Story Board may be beneficial and widely applicable in that it offers both verbal and nonverbal means of expressing one’s story across languages and levels of literacy (Buchanan, 2009; Riggs, 2015; Bopp et al., 2003; Chase et al., 2010).