Domestic Homicide Brief 10

October 2020

SUGGESTED CITATION:

Dufour, G. K., Crocker, D. (2020). Domestic Violence Safety Planning, Risk Assessment and Management: Perspectives from Service Providers in Nova Scotia. Domestic Homicide Brief 10. London, ON: Canadian Domestic Homicide Prevention Initiaitve with Vulnerable Populations. ISBN: 978-988412-41-2.

THE CDHPIVIP TEAM

| Co-Directors | |

|

|

|

|

Myrna Dawson |

Peter Jaffe |

Management Team

Julie Poon, National Research Coordinator

Anna-Lee Straatman, Project Manager

Graphic Design

Natalia Hildago, Communications Coordinator

This research was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Introduction

The current study is part of the Canadian Domestic Homicide Prevention Initiative with Vulnerable Populations (CDHPIVP). The CDHPIVP is an ongoing, collaborative initiative seeking to provide a comprehensive overview of the protocols, strategies, and barriers in relation to Risk Assessment, Risk Management, and Safety Planning in high-risk cases. The CDHPIVP aims to provide an in-depth look at risk factors specific to indigenous populations, immigrants and refugees, rural, remote and northern populations, and children exposed to domestic violence. This brief report analyzed a subset of interviews from the CDHPIVP’s larger ongoing project. This study examined interviews with key informants working in Nova Scotia in various sectors related to domestic violence. The goal of the current brief was a comprehensive examination of the training, protocols, and strategies available to and used by service workers in Nova Scotia.

DEFINITIONS

DOMESTIC HOMICIDE: The killing of a current or former intimate partner, their child(ren) and/or other third parties. An intimate partner can include people who are in a current or former married, common-law, or dating relationship. Other third parties can include new partners, other family members, neighbours, friends, co-workers, helping professionals, bystanders, and others killed as a result of the incident.

RISK ASSESSMENT: An evaluation of the level of risk a victim of domestic violence may be facing including the likelihood of repeated or lethal violence. It may be based on a professional’s judgment based on their experience in the field and/or a structured interview and/or an assessment tool/instrument that may include a checklist of risk factors.

RISK MANAGEMENT: Strategies to reduce the risk presented by a perpetrator of domestic violence such as close monitoring or supervision and/or counselling to address the violence and/or related issues (e.g., mental health, addictions).

SAFETY PLANNING: Finding strategies to protect the victim that may include such actions as educating victims about their level of risk, a change in residence, an alarm for a higher priority police response, a different work arrangement and/ or readily accessible items needed to leave the home in an emergency including contact information about local domestic violence resources.

We interviewed 22 service providers in Nova Scotia who work with domestic violence victims or perpetrators. A large proportion (41%) were in the Halifax/Central region and almost one-quarter (23%) were in the Cape Breton region.

Participants worked in a variety of sectors and fields including:

- Violence Prevention

- Victim Services

- Settlement Services

- Children’s Mental Health Services

- Police (Federal and Municipal)

- Counselling

- Children and Family Services

- Indigenous Family Healing Centres

- Perpetrator Treatment

- Restorative Justice

The CDHPIVP focuses on four population hubs at particularly high risk of domestic homicide. Table 1 shows the proportion of research participants working in each hub,

|

TABLE 1. PARTICIPANT CHARACTERISTICS (N = 22) |

||

| n | % | |

| Population Hub | ||

|

Rural, Remote, and Northern |

11 | 50 |

| Children | 8 | 37 |

| Indigenous Populations | 12 | 55 |

| Refugees and Immigrants | 14 | 64 |

|

*Percentages do not equal 100 as many participants work with more than one hub. |

Section 1

Domestic Violence Training in Nova Scotia

We asked participants what domestic violence training they had received in risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning. Commonly, participants received two different types of training: Explicit structured training and indirect training through professional development opportunities.

TRAINING TYPE 1: EXPLICIT STRUCTURED TRAINING

Explicit structured training applies to training for empirically validated risk assessment tools.

• More than half of participants reported explicit training in either ODARA (for recidivism risk) or the Danger Assessment tool (for lethality risk) or both.

• No other risk assessment tools were mentioned by any participants.

• Participants received training on-line and in-person. Some received in-person training from Jacqueline Campbell, creator of the Danger Assessment tool.

• Participants also reported receiving more frequent training for safety planning than they did for risk assessment or risk management.

“Three of us [at our agency] have actually been to several in person trainings with Jacqueline Campbell. At one point the Nova Scotia government was very keen on all of their justice people being trained. Not everybody on staff is certified to do it, and we only allow those who are certified to actually do that with clients.”

“A few of the staff received the training directly from Jacqueline Campbell, but that was a while ago that she was in the province to be able to, so the newer staff have only received the online training”

TRAINING TYPE 2: INDIRECT TRAINING

Indirect training occurs in situations where service providers learn about violence strategies through professional development opportunities or on-the-job situations.

“I think if you were to have me point on my resume where I was trained in risk assessment, I would have a hard time, but I think it’s kind of ongoing. We are aware of things in terms of certainly there’s been presentations and workshops that are focused on domestic violence, which are all about risk, signs of risk, and risk assessment things, so I think that yes, we’ve all had training on risk assessment, but […] I can’t remember ever going to a course that was called ‘risk management,’ but I think counselling is generally risk management so I’ve done many programs and training around narrative therapy, working in domestic violence, and those kinds of things.”

Nearly all risk management training occurs indirectly through professional development opportunities. In fact, not a single participant reported a specific or formal training for risk management. Rather, participants explained that they learned about risk management when being trained on:

• trauma therapy

• policing and investigating process

• mental health and psychology

• suicide intervention

• non-violent crisis intervention/de-escalation

• first aid

• addictions

• trauma-informed/harm reduction models

Regardless of the type of training received (explicit or indirect), most participants also stated that they continue to learn while doing their day-to-day work.

“[We do not receive] formal safety [planning] training.[…] We take a lot of training on domestic violence, we go to a lot training, we take a lot of online training, we do a lot of readings. […] We don’t have any kind of training that says “Okay, this is the safety planning training.”

Many domestic violence service workers also stated they frequently took advantage of other professional development opportunities such as conferences, presentations, seminars, programs, and educational events.

“There is all kinds of shared training that happens within our community. […] That’s sort of how we’re getting our training – through collaboration and our county partners and through presentations and those things once a month. You know we did the mental health and first aid training. There’s a lot of things that come up that when you have the opportunity, I try as much as I can to have at least one staff attend these things and then share it at staff meetings so we can better equip ourselves to work with women.”

Thus, beyond the few participants that receive explicit training on a tool, it is difficult to ascertain how consistent risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning training are across the province. Training and expertise will therefore vary among agencies.

Section 2

Domestic Violence Protocols in Nova Scotia

We asked participants about written directives, policies, or protocols that guide the work with victims or perpetrators of domestic violence. The most commonly discussed protocol in Nova Scotia is the High-Risk Case Coordination Protocol (HRCCP; https://novascotia.ca/just/publications/).

HIGH RISK PROTOCOL

Nearly all participants in Nova Scotia directly used, or were aware of, the HRCCP.

• Participants could all explain the initial designation process and the case update and case conferencing process.

• Participants understood and acknowledged the fundamental importance of ongoing inter-agency communication, information sharing, and collaboration built into the protocol.

• Participants acknowledged that the HRCCP requires involving all parties (service providers, victims, perpetrators, and family members/ children).

Most participants found the case conferencing aspect of the HRCCP to be effective, efficient, and helpful, stating “It is a very good collaborative process.” Further:

“I do believe there has been a lot of situations where those case conferences have really made a difference, I think it’s saving lives, and when women are involved in them and they see that everyone is paying attention and we are all invested in the safety of everyone here – the safety of not just the woman but the whole notion of the whole case is high risk of going badly – so those conversations – not just that he might kill her, but some of our situations are so drastic […] I have to say that the high risk designation and case conferencing is a wonderful way to support women who are in really dangerous situations.”

“There has been a lot of situations where those case conferences have really made a difference. I think it’s saving lives.”

Although much of the feedback about the HRCCP was positive, some participants noted several challenges. Service providers’ ability to contact the victim was a serious issue raised:

“At that point I’m trying to get a hold of the victim, now I always say trying because we have all kinds of things going on and usually domestic violence is not the only scenario and reaching the client may not always be easy, they may have gone to the shelter, they may have a telephone and the bill isn’t paid, so getting a hold of them may not be easy. […] We ask the officers if they can get a secondary phone number [such as] the mom’s phone number, we utilize that information as well to try and reach them.”

One participant expressed concerns that police do not inform perpetrators that they are high risk:

“One of the big issues here in Nova Scotia which has been talked about and never been dealt with, and it’s one that can put a woman at risk, it’s one that can put a child welfare worker at risk, is the accused is never told if he is high risk [by the police]. […] When there is a high risk domestic, child welfare has to meet with the woman, assess any risk or dangers, she also has to meet with the accused to see if they’re going to be looking at having supervised visits and unsupervised visits, and what avenue they’re going to take. So when [the child welfare worker is] telling a man “no you’re high risk” and he has no idea about this, it is a major gap here in Nova Scotia.”

DESIGNATING THE LEVEL OF RISK

A high-risk designation is made when a relationship meets a certain threshold on a risk assessment tool. Many

participants noted that a high-risk designation changes the system response to the case:

“If someone comes in high risk, they’re prioritized ahead of someone who’s just a regular probation person. So, I try to see them sooner.”

We heard some concerns about cases that appear, on the face of it, to be high risk but do not meet that criteria on the risk assessment tool:

“The potential for him killing her and the children and himself were extremely high. So sometimes when we have low scores [on the ODARA] police will still designate the file. And his score was a 2 and his file they were designated high risk. We were able to put programs in place for them and we were able to get her moved to a safe location to get him treatment.”

Many participants indicated that they can “up” the risk designation if they feel it is necessary.

“When I’m training members too, and I’ve had members come say look “It’s only hitting a 5, I don’t know if it’s high risk I don’t know what to do” I’ll say to them “what is the difference that it’s high risk or not high risk? If you deem it high risk, then we know she’s getting all the services. We know that everything that could be offered is being offered. So don’t get stuck on “it’s not hitting 7”, if you think there is risk or concern, or if you’re going home after work tonight and you may think if you wonder if she’s in trouble, then you should be designating it high risk.”

A handful of participants also noted that because the designation process works in this way, there will always be cases that are not designated as high-risk. However, in these cases, it can become problematic to use language such as “low risk” as that might be an underestimation of danger.

“If we overestimate risk, okay. But if we underestimate risk, that’s problematic.”

“If we overestimate risk, okay. But if we underestimate risk, that’s problematic. Sometimes by using risk assessment tools, the message that gets sent is if it’s not high risk, well […] And a number of [workers] in the province used to say, “well, if it’s not high risk, what is it? Is it low risk and what does that mean?” So, in transition houses, women who have scored as high risk receive pretty much the same services as women who are considered, I don’t know, low risk? Because we don’t know! You can’t assume that anyone is not high risk.”

OTHER PROTOCOLS

We also asked participants about any written directives, policies, or protocols they had been provided beyond the HRCCP. Participants noted that police must do ODARA in certain circumstances. For instance:

“With police an ODARA is required if it meets the threshold. So police go to a scene that they believe there had been either a domestic assault or a threat with a weapon in hand; if one of those two things happened, they are required to conduct an ODARA and then that ODARA goes on the police file […] The Danger Assessment is optional. The DA isn’t done automatically. It is something I will specifically ask a victim, tell them what the Danger Assessment is, the purpose of it is, and ask them what they’re comfortable doing one with them.”

However, for other positions (such as counsellors or healing centre workers), risk assessment is only used when the worker feels it is necessary.

• About half of participants stated they did not have extra risk assessment specific policies.

• However, several other participants stated their agencies did have additional individual written policies. For instance:

“We also have a child protection protocol as well. We have an emergency protocol where if a client maybe is in a state of disruption and may be putting themselves at risk and our staff at risk.”

Regarding risk management, less than a quarter of participants said they were given written policies and directives beyond that which is outlined in the HRCCP.

• Many noted that the case conferencing model was their primary protocol for risk management and reduction.

• Interestingly however, many participants who did not have protocols for risk management stated that they felt like they did not need them, because every case is different. However, participants who did have risk management protocols noted they found them useful.

Conversely, the majority of participants had been supplied with explicit written directives on safety planning. Although all service providers have directives to do safety planning there is no step-by-step directives on “how” to do safety planning in the HRCCP. However, many participants noted their individual agencies had policies and handbooks that explain how to do safety planning (step by step). Most participants also stated part of safety planning “protocol” is to use one’s professional judgement. For instance, there are case-specific issues that a written protocol cannot predict:

“We have the safety conversation tool of course, but safety planning is just embedded in the work that we do in talking with women. One of the pillars of those conversations and whenever there’s an issue identified, looking at what are you concerned with? What are your strategies around that? What support do you need for that? Again, trying to build on the resources already being used by the woman, but as far as our formal policy goes, you know, we do have a policy that safety planning is done to the best of our ability with every client who’s seeking our services and it’s tailored to their needs.”

Section 3

Commonly used Strategies

We also asked participants about other commonly used strategies they used for risk assessment, risk management, and safety planning. Many participants stated that their professional judgement was one of the most important strategies available to them: “I think so, you can’t not. It would be negligent if we didn’t [use professional judgement].” Further:

“I say that if you use a tool of any kind, it’s just a guide. Some of these questions are simply only to guide your thinking to a certain way. And I often say to women themselves, sometimes they’re the expert. I think I’ve learned a lot from them – more from them than anything else.”

RISK ASSESSMENT

Most of the participants who do risk assessment in their work use pre-structured tools or interviews (ODARA and as described above).

A few participants described other tools, such as flowcharts or checklists, and suicide assessments. As noted above, many participants claimed professional judgement might sometimes override a formal tool. However, professional judgement is also used as a strategy for many other parts of risk assessment, such as:

• Deciding how to handle extraneous disclosures

• Knowing when to make referrals

• In counselling or clinical settings:

“Within our counselling conversation and engagement with clients, we would look at indicators that would tell us their ongoing or limited risk. This is through professional judgement. We don’t actually use a risk assessment tool. We base our evaluation of risk on our conversations and our clinical supervision that is provided to our therapists. They would bring a client situation into clinical supervision to determine risk. And that could be risk to self, could be risk to partner, risk to children.”

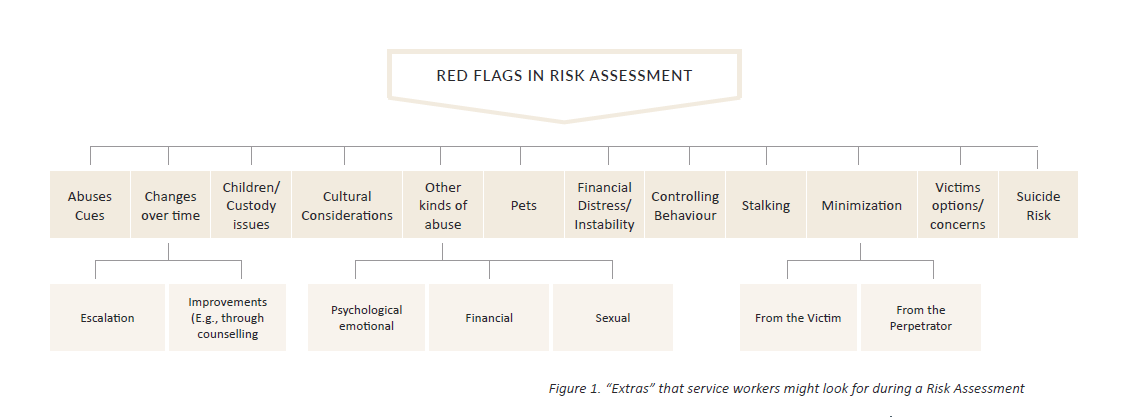

Looking for additional red flags that might not be accounted for by a tool. See Figure 1 for some examples of such red flags.

Red Flags in Risk Assessment

Figure 1 "Extras" that service workers might look for during a Risk Assessment

Abuses cues, changes over time, children/custody issues: escalation, improvements (e.g. through counselling)

Cultural considerations, other kinds of abuse:

Psychological/emotional, financial, sexuak

Pets, Financial Distress/Instability, Controlling Behaviour, Stalking, Minimization, Victims options/concerns, Suicide Risk: From the Victim, From the perpetrator

RISK MANAGEMENT

Risk management was identified as the most ongoing, resource intensive process. For this reason, many participants noted that the funding, time, and resources required for effective risk management for every case is not always possible. This was explicitly identified as a barrier to effective long-term monitoring and supervision.

“I think risk management is necessary. I don’t think we have the resources to do that kind of risk management properly. I think the resources that we do use do the best they can, but there are so many gaps and I think there’s so much of a lack of resources that those people fall through the cracks.”

“I think there’s so much of a lack of resources that those people fall through the cracks.”

The risk management strategy identified the most often is multi-agency collaboration.

- Most participants noted that risk management almost always involves referrals to community services, agencies, programs, and counselling services.

- Case conferencing (through the HRCCP) was identified by nearly half of participants as an integral step in managing and reducing risk.

“Really it comes down to things that we had talked about and then navigating… we have knowledge of other local supports that we can point them in the direction to, like mental health, addictions, therapy, or where there are other programs going on.”

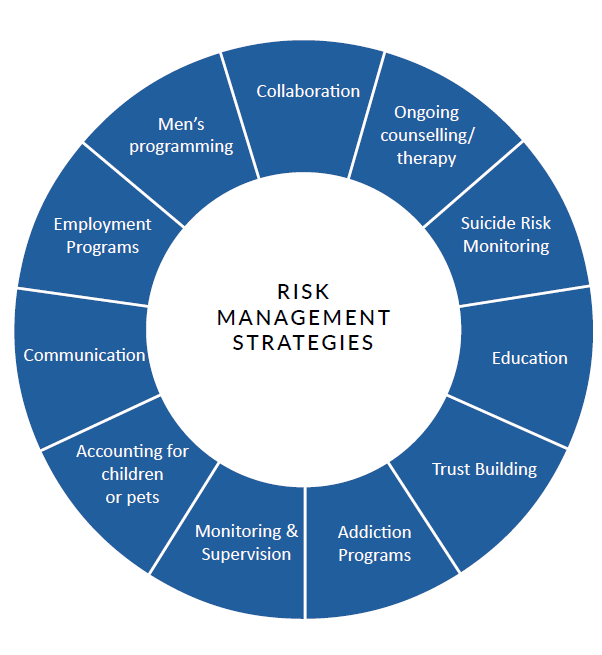

Other factors that were identified as critical to effective risk management can be found in Figure 2.

Finally, participants indicated that men’s programming is integral to effective risk management. Such programs involve domestic violence court and counselling, as well as housing, parenting, employment programs and support. However, as one participant mentioned, “There’s not as much services for the accused as there is for the victim” and this could therefore be a potential gap in service.

“There’s not as much services for the accused as there is for the victim.”

Figure 2. Risk Management Strategies

Collaboration, Ongoing counselling/therapy, suicide risk monitoring, education, trust building, addiction programs, monitoring & supervision, accounting for children or pets, communication, employment programs, men's programming

SAFETY PLANNING

When asked about strategies for safety planning the most prominent theme from the interviews is that safety plans should not be ‘one-and-done’, but rather, effective safety planning is typically ongoing, and a significant amount of planning and education happens orally, in conversation.

“I’ve always said that safety planning can be anything from an hour long discussion about how you’re going to respond to this, and this, and what you’re going to do, and safety planning could also be a quick call from a client that we’ve never heard from before, getting her name and address so that if she’s telling us she’s scared and in real danger, trying to get her name, address, phone number registered on our crisis sheet so that if something happens while she’s on the call with us we can dispatch police.”

The content of a safety plan will also depend on the client’s needs. For instance, participants identified two general types of safety planning. A victim might require one or the other or both.

Safety Planning Type 1: Immediate Safety

Immediate safety plans included what was referred to as the “nuts and bolts” of safety planning:

- door locks,

- alarm systems

- having a bag ready

- safety around the vehicle

- protecting documents and paperwork

- being willing to call 911

Safety Planning Type 2: Longer-Term Safety

Conversely, longer-term safety planning themes included:

- Safety planning in the workplace

- Safety planning around addictions and mental health issues

- Including other people in your plan (employers/ supervisors, coworkers, neighbours, landlords, children).

However, there were many other strategies that also emerged in safety planning with domestic violence victims. For instance, most participants explained that safety planning must be tailored to individual victims, should build on individuals’ strengths, and typically include:

- What has worked in the past?

- Multiple backup strategies

- Flexible strategies

“Listening to women about where their fears lie and trying to discover in conversation with them, what are they already doing? Where are they already finding strengths and safety and how can we build on that? And always listening for the nuance. […] It’s when someone calls you and has said “things are going fine, family court order’s in place, he’s been visiting the kids,” and then a week later you hear, “I haven’t been sleeping much lately, probably just stress.” […] So listening to nuances and not making assumptions. Not assuming that what she’s saying is what you think you’re hearing.”

“What is working today may not be working next week. You have to adapt your safety plan to things that are going on around you.”

“The one thing we need to communicate with women [is] what is working today may not be working next week. You have to adapt your safety plan to the things that are going on around you, and how your life is changing. […] So I always had a problem writing down safety planning complete, because I never believed that it was completed.”

Another critical theme that emerged about safety planning is the need to set “reasonable expectations.” That is, to be aware of the means and resources available to the client and plan accordingly:

“It has to be her plan, right? It has to be a plan that actually works. For example, saying to a woman that she needs to get an alarm system when she doesn’t know where her next meal is coming from is not practical and unfortunately, I’ve seen some government folks say that to women, ‘well you just need to get an alarm system.’ Well, who’s going to pay for it? And then the government folk would get on her case because she’s not being cooperative and she didn’t change all the locks in her home or something, but she had no money to do it. […] So, the plan has to be practical and she has to recognize those risks and she’s got to want to have a safety plan, and the plan has to be practical.”

This often means that a degree of creative problem solving is necessary. For instance:

"Telephone contact, that’s a challenge. So for example, how do I notify my neighbour, if I want my neighbour to know there’s something going on in the home how do I do that? […] Women will often talk about “the blind on my window, I just pull my blind up and she sees my blind up then she knows” or “if my blind is closed”, you know, they will determine what that signature message is that the neighbour will look for. […] Another thing is that not all homes have blinds in them, not all the homes here in our First Nations communities have curtains either, it might be a blanket or a garbage bag. So again, trying to be creative we tell our women “if it’s a garbage bag then you rip that garbage bag down from the window”. So that might be the message to your neighbour or relative next door to say “oh my god the garbage bag is down I gotta get over there or call 911” whatever that looks like right?”

The other critical safety planning strategies identified by many participants in this study include:

- Technology and social media-based safety

- Education and communication

- Advocacy on behalf of the victim – such as with employers and landlords.

- Referrals to other services (transition houses, counselling or trauma therapy, women’s shelters, financial aid, child protection, and police protection).

Section 4

Collaboration, Communication, & Information Sharing

Case conferencing is key to the HRCCP. It requires collaboration and communication between multiple agencies regarding initial risk designation and relevant case updates. The vast majority of participants agreed they had the means available to communicate when necessary.

The principal agencies involved in case conferencing in the HRCCP include:

- transition houses

- police

- victim services

- child protection services

- corrections and probation and

- men’s intervention programs.

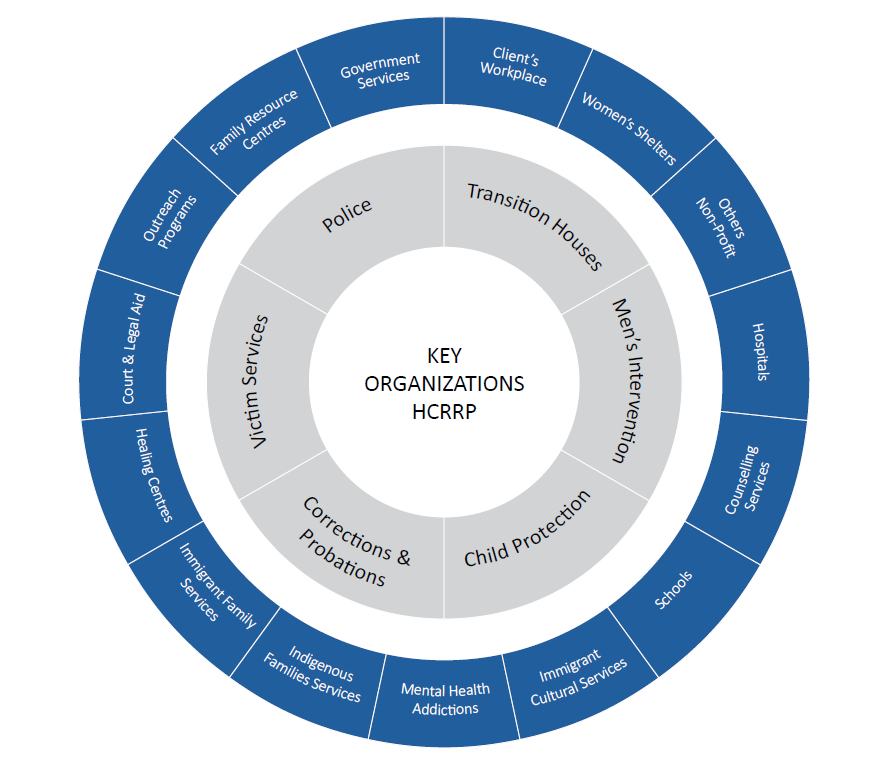

Although these are the organizations most involved in a given case, a number of other organizations might become involved depending on client needs. Figure 3 provides a visual representation of the organizations identified by participants.

Figure 3. Visual Representation of 6 Key Organizations (grey) and Additional Organizations (blue) that might be involved in Case Conferencing within the HRCCP.

6 key organizations (grey) : Key Organizations HCRRP: Transition houses, men's intervention, child protection, corrections & probations, victim services, police

Additional Organizations (blue) that might be involved in Case Conferencing within the HRCCP: Client's workplace, women's shelters, others non-profit, hospitals, counselling services, schools, immigrant cultural services, mental health addictions, Indigenous family services, healing centres, court & legal aid, family resource centres, government services

WHAT INFORMATION IS BEING SHARED?

Unique to the HRCCP is the standardized way in which information is shared between organizations. There are two ‘Forms,’ (like an update) which are created by one agency and shared with the other organizations so that all collaborators on a case have the same information.

“Form 1” is the initial high-risk designation on a case. The form is issued by the Department of Justice, and contains the contact information from the risk assessment, and what charges were laid. It is then sent out to the primary service providers so that all agencies are aware that a case has been designated as high risk. Once a client is referred to an organization, Form 1 allows for service providers to have the initial information required to make professional assessments.

“Form 2” is a follow-up to Form 1. It provides relevant updates (or “critical developments”) regarding a high- risk case, such as when the victim has a new partner, the perpetrator has breached an order, or a court date is approaching. These are all factors relevant to risk management and safety planning and can increase the risk to the victim. Similarly to Form 1, Form 2 is distributed to the relevant organizations so that, when applicable, those service providers can respond appropriately and in a timely manner based on the updated information.

“Corrections will send out what we call Form 2, so the critical developments when risk is increasing, so then when we receive that we’re calling the woman just to make sure if we need to do anymore safety planning, and to make her aware of the risk that Corrections is seeing at this point in time.”

In addition, some clients provide collateral information that might warrant sharing with other services. Such information might include disclosures of increased fear, or new instances of stalking. Information sharing typically happens via the case conferencing model:

“One of the things that we do, and this happens from time to time, is we can hold what’s called a case conference. So, let’s say there is a situation where she’s extremely terrified and she may be limited with resources and usually financial is one of them, maybe housing is another concept, in many cases they’re living within very close proximity of the abuser and that increases your danger.”

BARRIERS TO INFORMATION SHARING

Participants identified few barriers to information sharing, but they did mention concerns about what types of information to share and the quality of information being shared. For instance, one participant noted:

“So that’s quite frustrating. […] Some probation officers are very on it, forthcoming with information and they have good detailed paper work when I get a referral. Others just send along the basic contact information and the formal order for the court and then I go from there.”

Victim consent was the biggest barrier to communication and information sharing

- Victims must consent to having their information shared (even with the HRCCP in place). When victims do not consent, confidentiality presents a barrier to effective communication among agencies.

- Consent is particularly an issue when working with outside organizations (such as the blue circles in Figure 3), as lack of consent prevents service providers from sharing all the information about a case, some of which might be critical to safety

- Some women are hesitant to allow information sharing because they are afraid it might work against them:

“I think sometimes the confidentiality is killing people, but I also think at times that why some of our women are so adamant about maintaining their confidentiality is because it’s the only thing they have control of and when they get sucked up into the system, they have no control. […] In talking to a lot of women who have been victimized, they want to tell their story, but they don’t want to give their life away either. They want to […] have their story be respected. […] It was difficult even as a DV coordinator for me to even get women to attend case conferences, which I think are really valuable tools, but only if everybody at the table is there under the same understanding. [The] first couple of case conferences I organized, child welfare came with a notepad and I think after the third case conference we did, they were saying to the woman “we’re going back to the shelter with you because we’re going to be taking your child” […] If we’re there gathering information to use against her then how can she feel safe? And why should she open up? I mean, I wouldn’t.”

“I think sometimes confdentiality is killing people.”

Thus, there are some cases where the victim might be in serious danger but does not consent to having their information shared. In those cases, there is a degree of professional judgement required to make decisions about information sharing.

“Sometimes you have a woman who does not want you to communicate that, but if we think that we have a case that warrants a high risk designation, but the woman herself is not willing, then it comes down to us as a staff team making a decision and we’re upfront with people in that if we think the situation is extremely dangerous we may still involve the other partners, but that is not a decision we take lightly.”

Section 5

Challenges & Barriers with Vulnerable Populations

As noted earlier, the CDHPIVP’s aim is to take an in-depth look at four distinct populations who have been identified as high risk. These populations include:

- Children exposed to domestic violence

- Rural, Northern, and Remote Populations

- Indigenous populations and

- Immigrants and refugees.

We were interested to know what specific challenges service providers in Nova Scotia face when working with these populations. We describe some of the biggest issues identified with each group below.

CHILDREN EXPOSED TO DOMESTIC VIOLENCE

Concerns relating to the role of parents

- Parents who use their children as pawns against the other parent (such as in custody, visitation)

- Parents who try to “make it work” for the sake of the children, ultimately resulting in increased exposure to

Lack of services

- Lack of resources specifically for children who have been exposed to violence

- Need services to treat mental illness or trauma in children

History of violence and traumatization

- Development delays

- Behavioural issues

Housing

- Unstable housing or lack of safe housing options for families as a risk factor

Addictions

- In parents and in youth/adolescents

Child protection

- Some mothers may avoid contacting services out of fear of having their children taken away

- Stigma attached to being involved with child protection

RURAL, REMOTE, AND NORTHERN POPULATIONS

Transportation (identified by all participants)

- Related is the issue of isolation

- Women cannot travel or go places

Lack of services

- Inadequate funding and resources to handle the demand

- Limited services result in longer wait times for what is available

- Services that exist are not accessible due to distance – women have to leave their communities to access services. Some participants stated they had clients who were encouraged to re-locate for these reasons.

- Lack of services and programming for things such as employment, parenting, addictions, even phone and Internet services.

- Poor police response time

- Lack of safe and affordable housing options

Unemployment

- Lack of employment opportunities and/or employment programs

- Lack of education

- Lack of public education around awareness and impact of domestic violence

“Small town” attitudes and beliefs

- Shaming and blaming

- The belief that perpetators in small communities might be protected or defended if they are well liked, or that the victim will not be believed

- Issues around confidentiality (e.g., “I can’t go to that service because my abusers friend works there”)

Other Issues

- Poverty

- Poor internet and cell/phone service

- High prevalence of substance abuse issues

- Cloak of silence – “we don’t talk about that”, underreporting

INDIGENOUS POPULATIONS

Indigenous communities face distinct challenges and barriers that stem from the legacy of colonialism in Canada including:

- Being unable to access culturally sensitive/relevant services

- Feeling like they are “not welcome in White spaces”

- Racism and prejudice

Specific effects of colonialization and intergenerational trauma in relation to:

- High rates of poverty

- High prevalence of substance abuse and addictions Minimization and normalization of violence against women (and violence in general)

- Barriers around language, education and literacy

- Severely broken trust between Indigenous peoples and police resulting in fear of reporting family violence; imposition of colonial justice system rather than consideration for Indigenous cultural traditions.

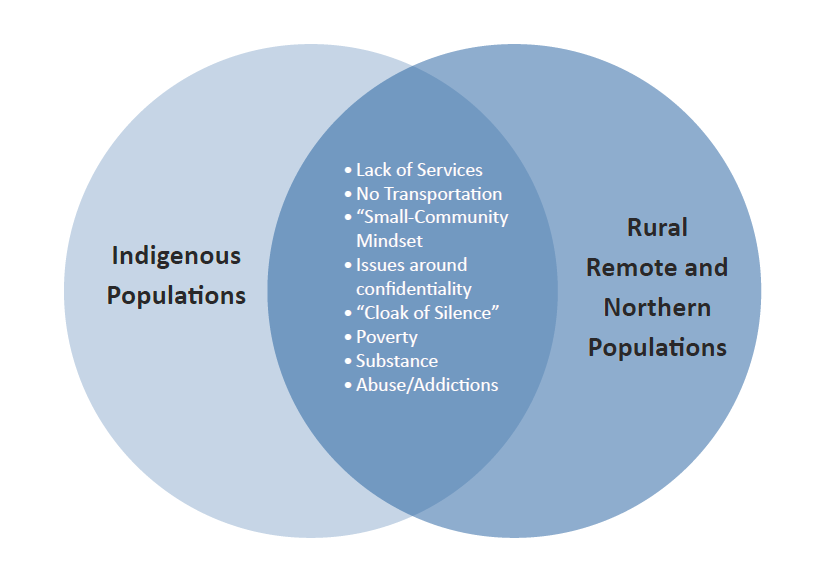

Many barriers outlined in the rural, remote, and northern populations were also reflected in Indigenous populations. Please see Figure 4 for a visual representation. Some examples are:

-

Lack of services

- poor police response time,

- poor internet and phone service,

- no safe housing options,

- not enough funding for resources,

- long waitlists

- Transportation (things are quite spread out and there is no transit)

- Issues around confidentiality

Middle: Lack of services, No transportation, Small-community mindset, Issues around confidentiality, "Cloak of Silence", Poverty, Substance, Abuse/Addictions

IMMIGRANTS AND REFUGEES

Language issues

- Lack of translation services

- Issues with confidentiality if the translator is from the abuser’s community

- Language barriers between victim and services/system

- Lack of resource materials available in other languages

- Coordination issues and slower process because they require translation services

Cultural issues

Lack of culturally relevant or culturally sensitive services

- Differing attitudes and beliefs

- About women, gender roles, ownership

- About social acceptability of abuse

- About victim blaming, shaming, and perceptions of options for women

Isolation

- Social

- Mental

- Physical

Fear, distrust, and lack of understanding of Canadian customs, laws, police, and legal system

- Lack of education about options and services for women about the laws and legal process

- Racism and discrimination

Stress and trauma

- Coming from politically unstable/war-torn countries

SOCIAL POSITION ISSUES

One of the questions asked of participants was whether social position issues can work together/compound risk (i.e. individuals who are at an intersection of multiple risk factors).

Overall, participants agreed that many social position related factors (such as ethnicity, gender, age, socioeconomic status) might aggregate and increase risk.

However, many participants noted that different barriers will affect people differently because of social location. There are also many other situation specific factors that might contribute to compounding risk, such as:

- Lateral violence

- Intergenerational trauma

- Personal history of victimization and trauma

- Addictions

- Sex work

- Poverty

- Isolation (physical or social – to be socially isolated can be quite damaging).

- When the perpetrator is high status:

“[If] the perpetrator is a well-respected, well positioned person in the community, no one wants to believe that this person behaved in this way so, it’s very difficult for that woman to access services. So, I find that each situation has its own unique barriers and risks.”

Section 6

Predictors of Lethality

Our interviews asked participants about specific predictors of lethality in high risk domestic violence cases in Nova Scotia. Below are some of the key factors identified as being associated to lethality:

“Cloak of silence”

- under-reporting

- victim blaming and shaming

- an unwillingness to talk about it

“There’s a cloak of silence around domestic violence. [For example] when we look at the statistics when they say 1 in 3 Aboriginal women are at risk of domestic violence, I absolutely believe it’s higher than that, and I believe that because statistics are based only on what’s being reported.”

Attitudes and Beliefs

- Gender Norms

“Another thing is cultural beliefs and traditions. Sometimes [the] faith that [they follow] may not recognize domestic violence and gender violence [as an] issue. So may be contributing to normalization in a way of the situation rather than dealing with it.”

Lack of social resources

- Lack of resources specifically for men

- Poor police response time

“I’ve talked to women and I’ve said to them, “well if that happens, call the police” and they say, “I’m sorry, but that’s cold comfort to me because the last time I called them it took them forty-five minutes to get there. I’m not feeling very confident about feeling safe.”

Distrust of police/distrust of CJS

- Lack of understanding of the system and the options available

“One gap [is] trauma experience from wars and things like that, how to trust police officers, how to trust the system, how trust the court, how to trust even the lawyers. So it’s not just about people coming from wars, but coming from the systems where you really cannot trust some of these systems because of high level of corruption.”

Mental health

- Substance abuse and addictions

“So those are the ones that cause the most sleepless nights because those things, the mental health and addictions, adds to the risk factor. That puts everything at a higher level of risk.”

Poverty

- Lack of access to education

- Lack of access to housing

“The other large barrier [is] housing and access to safe and affordable housing; there is a real lack thereof. So while a woman may come to shelter, where she goes after that is a challenge because it is very hard to find safe, affordable housing.”

When children are involved

“I think there are risk factors for children who try to intervene. Children will try to get in the way of fighting parents and to help mom, or whatever that might look like. Children often times get hurt that way because they do try to intervene.”

Access to guns and weapons

“I would say that there are very high levels of mortality issues really because the youth have often really high addictions, high prevalence in gun related violence and also the history of physical violence.”

Cultural issues

- Political and cultural differences

- Language barriers

- “Language – the most crucial barriers. Recently I worked with a woman that had tried to tell police of the detailed plan her husband had to kill her and daughter, wasn’t able to effectively communicate that.”

Isolation

- Mental or Social

- Physical

“I find when people are isolated they are much less aware of how the relationship is heading in the wrong direction. Especially women who are very confused about their own ideas, their own memories and it makes it difficult for them to make good decisions for themselves. I think the same things happen to men – they isolate themselves as well for fear of being caught or questioned or whatever and isolation is a big risk factor for things to escalate.”

Being a minority

- Lateral violence

- Ethnic Minority

- Gender Minority

“And our transgender population as well [...] I think, well I don’t know the stats if Im honest with you, but I suppose if you’re transgender you’re 100% at risk of dealing with some kind of abuse or violence in your life.”

Section 7

Promising Practices

Participants identified many promising practices that can contribute to a better ability to assess, manage, and reduce risk in high risk domestic violence cases. Some of the factors identified by participants in this study as promising practices include:

Accessible resources

- Language and culturally relevant services

“Our organizations have lobbied the service providers from different areas in terms of making their services more culturally competent or culturally inclusive or places were immigrants can feel that their needs will be understood and recognized.”

- Transition houses

“The outreach programs for the transition houses […] get underestimated in terms of the value of what they do. I know they have programs where the worker will go to the victim, and I think that’s hugely valuable and again, transition houses are consistently underfunded and undervalued in the work they do. That is one of the biggest benefits of them.”

Other accessible services:

- Counselling services

- Support groups

- Services for children

- Service workers from indigenous and immigrant backgrounds

- Safe and non-judgemental environments

“I think the best tool is how we respond, how we treat people, how we say we want to approach everyone in a non-judgemental way and that’s not really easy for the human conditions it’s something we all want to judge on some level.”

Restorative Justice & Domestic Violence Court

“I am really excited about the Domestic Violence Courts. It has a bit of that restorative justice and a little bit of a very diversion slant. And not moving people who are ready to accept responsibility, and who are willing to make changes, and who do recognize their behaviours and their harmfulness of that behaviour and who are willing to make those changes, that is very promising.”

Communication

- Communication with other services

- Communication with the client

“I think when you can have good communication and when you can take time. It’s a very simple thing, but taking time to really talk to the victim, really kind of get a handle on what their reality is and to be respectful of where they are. I think that is a step that’s often missed by especially government.”

Transparency of the criminal justice system

“Quite often men feel railroaded going through that court process and not understanding that court process. [Recently] we brought in a legal aid lawyer who specializes in family court and told them the process and the tools that are available for the clients and how they start something and here’s how they get some legal advice and support without burdening their economic situation. So, that was a big thing for them to be able to talk to a lawyer on a more casual level than lots of them are used to and be able to ask really honest questions.”

Trauma informed practices

“I really truly believe that if we’re going to make a shift in the work that we do, we need to focus on trauma-informed communities. We need to empower regular people in the community that they can do something about this.”

Education about violence

- For service providers, victims, and perpetrators

“I really feel that child protection needs far more education and learning about domestic violence so they can work with these families.”

- Strengths based approaches

“[Taking] into account the strengths and strategies that the woman has already identified for herself and builds those into the plan, as well as identifying her areas of concern. It’s not a concern that we’re saying she should have, it’s the concerns that she identified. So I think because it’s a woman-centered approach that it’s a promising practice.”

Resources for specific groups

- Vulnerable sector groups

- Rural, northern, remote

- Children

- Indigenous populations

- Immigrants and refugees

- Resources for Perpetrators

Section 8

Overarching Themes and Conclusion

Finally, it is important to draw attention to some overarching themes that were present across all topics and interviews.

THEME 1:

Professional judgement is your most valuable tool

“Yes. That’s our biggest tool, our professional judgement, and I think it’s really important that we do work as a team so we meet weekly to talk about these things. So as we are having conversations about what’s happening with our clients, other people are able to listen and help us make judgements about where people are and when we should be concerned and those kinds of things.”

Workers in this sector need to be aware of the importance of their professional judgement and to have confidence in their ability to make the right decisions when people may be in danger.

THEME 2:

Case management is ongoing

“I also think that safety plans are not something you do once with someone and check that box off it’s done. I think it’s an ongoing thing and we need to be teaching people how to do their own safety plan.”

Every part of case management (from risk assessment, to risk management, to safety planning) should be ongoing:

- Risk is ongoing. Things change quickly.

- Getting to know a case is integral so you can look for little hints and changes that might signal a bad event.

THEME 3:

It’s about the little things

“Domestic violence is like peeling an onion because there are many layers to it. […] There’s so many pieces, there’s mental health, addiction is so predominate that I would say about 80% of my files is addiction related, financial pressure, children when they’re separated, when there is a new relationship...”

In many (or most) cases, a critical part of the process is looking for the subtle shifts and changes over time, as well as more nuanced aspects of a case that might indicate risk

THEME 4:

Victims are the experts in their own cases

“In my opinion the victim is the expert in her own life, so she knows what she’s to do to keep herself safe. And certainly I will suggest things that may keep her safe, but I don’t direct her to do things. And some of the organizations will directly order her to do this or to do that which a lot of times backfires because she either doesn’t hear it or is overwhelmed by everything she’d heard.”

Further:

“Even if a [Danger Assessment] score doesn’t score high but this woman believes she could be killed, sometimes we have to look at that and at the end of the day, she is the expert of her life and knows the partner better than anyone, so we take that serious. […] If she says, “you know what, he’s going to do it. He will do it.” Then we say it’s high risk.”

THEME 5:

We aren’t done yet

“I’ve been doing this work now for […] thirty-five years - when I first started I thought ‘we’re going to, as a society, we’re going to make it safer for women and children and they’re not going to have to worry about being abused and violated’. And here we are thirty-five years later and we’re still trying to do the same thing. There has got to be a better way. […] So, it just seems like such a monumental task and we’ve put all the effort, all the volunteers, all the paid positions, all the government money, whatever, and we’re still doing the same thing.”

- Many participants acknowledged that domestic violence services have come a long way and are improving.

- However, many participants also noted that they feel like we are still doing the same thing (some noted they felt like cases were getting worse, getting more complex).

- However, many participants also noted that they feel like we are still doing the same thing (some noted they felt like cases were getting worse, getting more complex).

This brief report provided an overview of domestic violence response protocols in Nova Scotia. It was written with the goal of better understanding the risk factors of domestic homicide in this province. Training and support for service providers is clearly an integral aspect of assessing and mitigating risk. This is particularly critical for cases with high risk or vulnerable clients. Nova Scotia’s HRCCP effectively facilitates inter-agency communication and information-sharing in these cases.