October 17, 2017 | London, ON

Acknowledgements:

The authors wish to thank Corinne Qureshi and Kristina Giacobbe for preparing the data for analysis for this report, and the CDHPIVP research assistants and students who were note-takers for the meeting. Thank you to all who attended the meeting for their input and contributions: co-investigators, students, research assistants, collaborators and partner organization representatives. We are grateful for the guidance of Myrna Kicknosway, Visiting Elder, Western University.

Suggested Citation:

Straatman, A.L; Dawson, M., Jaffe, P., Campbell, M. (2017). CDHPIVP Mid-term Partnership Meeting Report. Canadian Domestic Homicide Prevention Initiative with Vulnerable Populations.

ISBN:

978-1-1988412-15-3

Graphic Design:

Elsa Barreto, Digital Media Specialist, Centre for Research & Education on Violence against Women & Children

Aleksandra Rakić, Digital Communications Assistant, Centre for Research & Education on Violence against Women & Children

Introduction

The Canadian Domestic Homicide Prevention Initiative with Vulnerable Populations (CDHPIVP) is a five-year Partnership grant (2015-2020) funded by the Social Sciences Humanities Research Council (SSHRC). The project is examining risk assessment, risk management and safety planning practices for four populations:

- Children exposed to domestic violence

- Indigenous

- Immigrant and Refugee

- Rural, Remote and Northern (RRN).

In initial meeting of the partnership was held in October 2015 to introduce the project, clarify the governance model, identify research to be undertaken and seek input from partners and collaborators. A subsequent meeting of the CDHPIVP was held in London, ON, October 17, 2017 prior to the Canadian Domestic Homicide Prevention conference. This meeting provided an update to CDHPIVP members on work completed to date, sought input on effectiveness of the partnership and research activities. This report provides an overview of the Partnership meeting presentations, discussion and midterm partnership evaluation.

Project Updates

The CDHPIVP Management team presented an update on activities of the project since its inception in June 2015 which included the following:

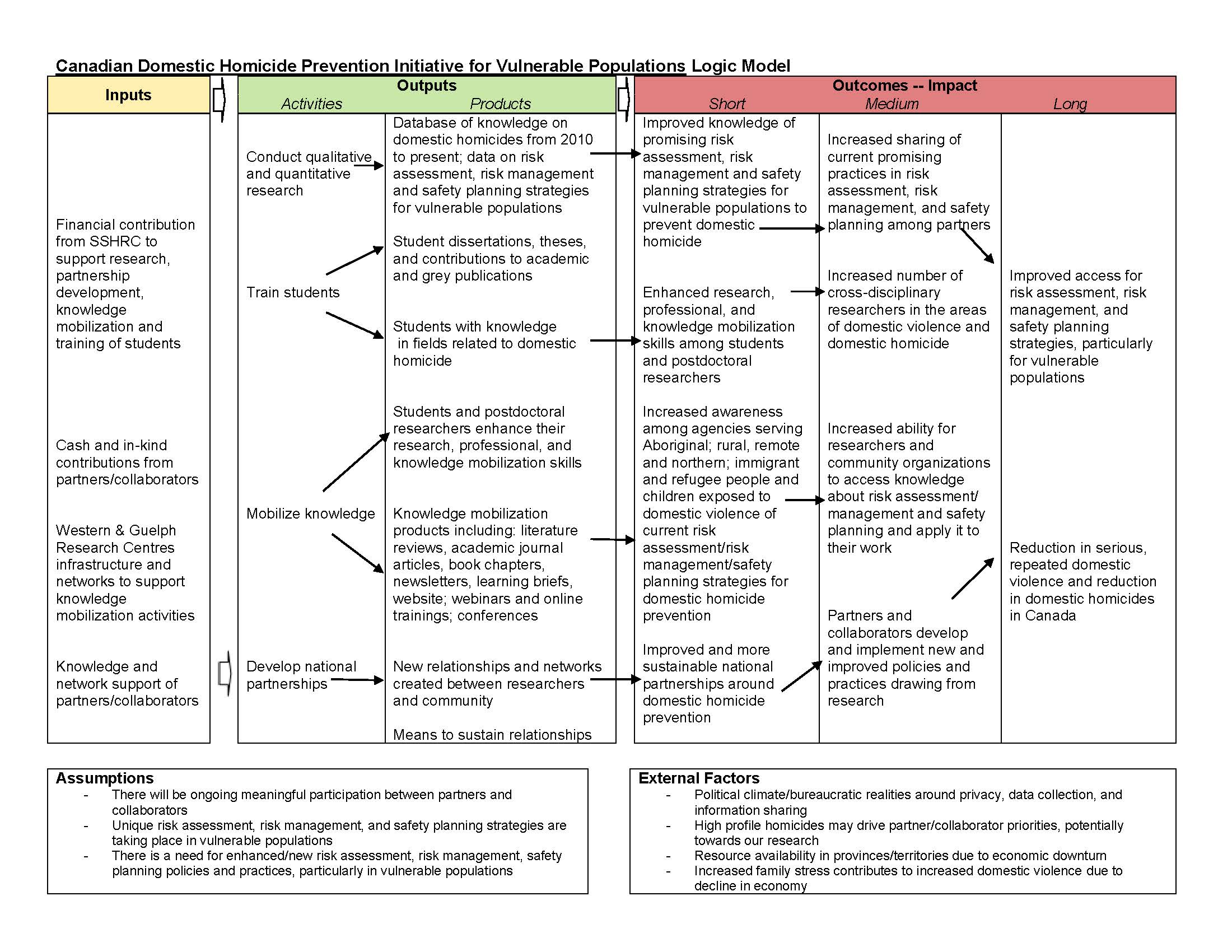

- Review of the Governance Model

- Logic Model

- Research report

- Knowledge mobilization activities

- Partnership evaluation

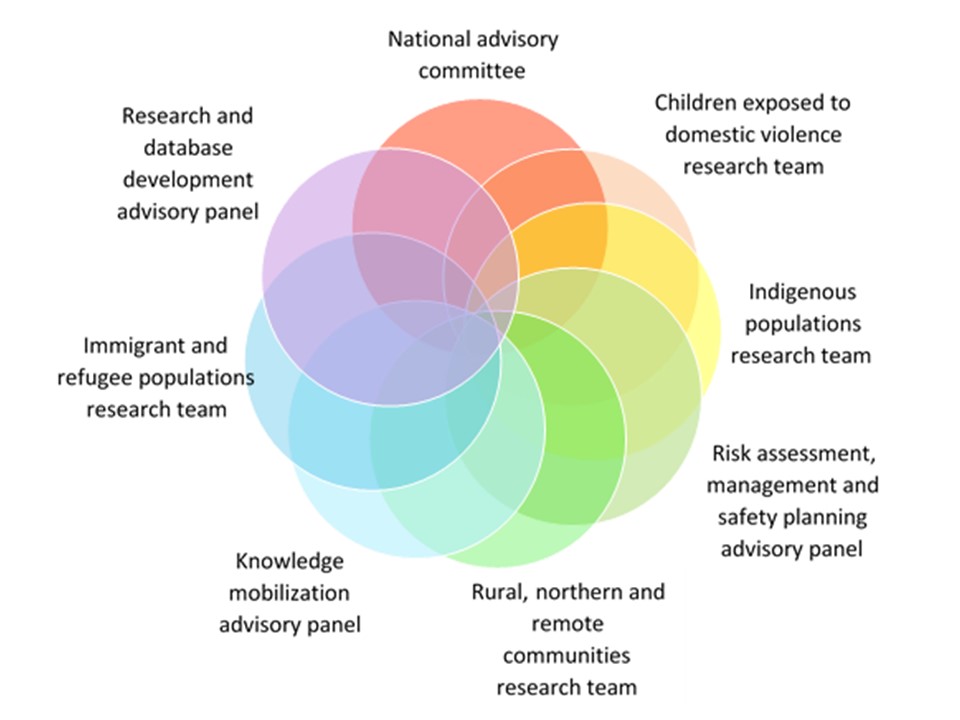

Governance Model

The Governance Model represents the intersectoral, collaborative nature of the project (Figure 1). Partnership members are welcome to join and contribute to as many teams or panels as they wish. It is understood that there will be overlap among groups as no group stands

alone without impact from another section. The project is run by a Management Team consisting of Dr. Peter Jaffe, Dr. Myrna Dawson, Marcie Campbell and Anna-Lee Straatman. Oversight is provided by the National Advisory Committee, consisting of six co-investigators and leads from each team or panel. Partnership members and their roles are identified in Appendix A. Communications with partnership members are conducted via teleconference meetings, email, website, Basecamp, bulletins, etc.

Figure 1. CDHPIVP Governance Model

Logic Model

A Logic Model (Appendix B) was developed to identify the goals, objectives, and outcomes for the project and informed the evaluation plan. The Logic Model was submitted to SSHRC with a Milestone Report in May 2016. The Milestone Report laid out plans for research, knowledge mobilization, training and mentoring, partner engagement and evaluation.

Research Report

Three research projects are being conducted through this initiative: 1) national domestic homicide database; 2) online national survey and key informant interviews on risk assessment, risk management and safety planning; 3) trauma-informed interviews with survivors of attempted homicide and proxy interviews for homicide victims. Ethics approval has been received for the first two projects at all eight sites, and licenses have been obtained to conduct this research in the northern territories.

Domestic Homicide Database

A research protocol for collecting data on domestic homicide cases from coroner and medical examiner offices has been developed, and agreements are being negotiated with all provinces and territories to access information to build a database that documents the total population of domestic homicides. There have been some challenges in obtaining consent from coroners and medical examiners regarding data collection for the homicide database. We received feedback identifying concerns about combining data from media and court records and coroners/medical examiners into one database, and maintaining privacy and confidentiality. To address these concerns, we are developing two databases: 1) data from court and media files; 2) data from coroner and medical examiner files. The two databases will not be linked. Ethics approval has been received from the eight universities involved in the project. We are in the process of signing agreements with coroners and medical examiners, but may not be successful in receiving approval from all jurisdictions (currently Alberta has declined to participate). In this case, we are reaching out to policing agencies as one alternate source of data. To minimize delays in data collection, we have proceeded with gathering court and media files on domestic homicides and are now coding data for this second database. Court and media files for more than 500 domestic homicides between 2010- 2015 have been retrieved and coding has been completed on about half of these files.

The CDHPIVP defines domestic violence homicide as the killing of a current or former intimate partner, their child(ren), and/or other third parties. An intimate partner can include people who are in a current or former married, common-law, or dating relationship. The term dating will be used in its broadest sense. However, we want to distinguish domestic violence from violence committed by strangers – a prior or ongoing relationship allows for meaningful risk assessment, safety planning and risk management strategies. Other third parties can include new partners, other family members, neighbours, friends, co-workers, helping professionals, bystanders, and others killed as a result of the incident. Domestic violence includes all forms of abuse including psychological or emotional abuse that has been documented through professionals or interviews with friends, family, and/or coworkers.

Given this broad definition, the number of homicides to be included in the database will be greater than the data available on spousal homicides provided by Statistics Canada. Figure 2 provides graphical representation of the number of homicides and spousal homicides identified by Statistics Canada compared with those identified by the CDHPIVP.

Figure 2. Domestic Homicide Cases From 2010 to 2015 By Province Based on Definition

Statistical Comparison of Statistics Canada Figures and CDHPIVP Domestic Homicides

The discrepancies between the Statistics Canada and CDHPIVP figures are attributed to differences in definitions. Statistics Canada includes legally married, common-law, separated common-law, divorced, current and former same-sex spouses of victims 15 years of age or

older when identifying cases of spousal homicide. This definition excludes boyfriends, girlfriends, extra-marital lovers, ex-boyfriends/girlfriends and other unspecified intimate relationships for both same- and opposite-sex relationships.

The CDHPIVP will continue to identify domestic homicide cases through media and court reports, and conduct validity checks on cases identified. The domestic homicide database will include data from 2010 to 2020.

Input was sought on other potential sources of information. Suggestions included: (1) femicide lists maintained by organizations such as OAITH and EVABC; (2) data from police services, hospitals, shelters and the World Health Organization; (3) data on child homicides

may be available from child advocates in each province; and (4) data regarding Indigenous women may be obtained through the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women Inquiry and Amnesty International.

It was suggested that the Co-directors seek standing at a national coroners’ meeting to present the research program and seek support. Additionally, the CDHPIVP may seek support from coroners already involved in the project to influence other jurisdictions, advocate on our behalf.

Survey and key informant interviews

An online survey was launched in January 2017 with a positive response rate. With support of co-investigators, collaborators and partners, more than 1,400 professionals who work with families experiencing domestic violence completed the survey. The survey sought volunteers to participate in interviews. More than 400 people volunteered to be interviewed (Figure 3). Interviews are being conducted based on the following criteria: regularly or frequently conducts risk assessment, risk management or safety planning; provides services to at least one of

the vulnerable populations identified; and contributes to geographic representation across Canada. The initial goal was to conduct 200 interviews but additional interviews will be required to meet the numbers required for representation across sectors, geographic location and population. As of October 17, 2017, more than 200 interviews had been conducted. These interviews are still being conducted and we anticipate they will be completed by December 31, 2017. A team of undergraduate and graduate students are currently transcribing the

interviews. Thematic analysis will commence in Winter 2018.

Figure 3. Participation Results for National Online Survey

1405 survey respondents from across Canada participated. 490 volunteered to participate in interviews.

CDHPIVP partners provided input on possible research questions to explore with the data collected through the homicide database, online survey and key informant interviews. The exploration of collaboration, communication and information sharing challenges and successes were considered important research priorities. The CDHPIVP was encouraged to further explore intersections – not isolate findings to the four research hubs. Questions and topics to explore include:

- Do service providers feel confident with tools used at organizations? Do they feel that there should be alternatives? Adaptations?

- How does the mainstream population become more aware of vulnerable groups?

- Do service providers refer to culturally sensitive services/collaborations?

- Examine adapted/non-mainstream tools and compare what is assessed

- Are the dynamics in cases of chronic domestic violence where the couples never separate different from cases of separation/repeated separations?

- Should there be research on short-term relationships that may be associated with dating or online dating sites?

- How many DH victims attempted to access shelters? Crisis supports?

- How do we assess the impact of domestic violence on Indigenous women who left their home communities and were killed by strangers? Are there existing databases that we could access to identify these victims and perpetrators?

- How do we deal with cases of missing or unidentified women?

- Comparative analysis with other countries

Interviews with attempted homicide survivors and proxy interviews for homicide victims

The third research project which will be undertaken involves comparing domestic homicide cases with attempted homicide/severe abuse cases. This research involves conducting interviews with survivors and proxies for homicide victims to learn about risk factors, any risk

assessment, safety planning or risk management plans that were put in place, effectiveness of the plans, missed opportunities, and initiatives that helped saved lives. Things to consider as we move forward with this research include:

- How to measure attempted homicide/severe domestic violence

- How to identify relevant proxies for domestic homicide victims

- How to recruit, sample and screen for victims and proxies of victims

- How to conduct the research in a trauma-informed manner

Dr. Jackie Campbell presented lessons learned from the multi-site intimate partner femicide study research she conducted in the United States. Vicarious trauma, staff selection, identifying proxies for homicide victims, importance of establishing a control group, definitions of

attempted homicide, recruitment strategies, identifying involvement of children, use of language were identified as topics for consideration when proceeding with this research.

Meeting participants were asked to provide input on the topics addressed by Dr. Campbell and those presented above. A summary of these discussions provided below will inform the next phase of research and ethics submissions.

Ethical recruitment and identification of research participants

Suggestions for identifying and recruiting research participants include:

- Working collaboratively with community partners, cultural and religious leaders, elders, to identify possible participants, make contact, introduce and describe the project

- Making presentations on the topic to a community to introduce the research study in community settings, asking for people to come forward

- Connecting with survivors through shelters, support groups for bereaved families, police who bonded with family members through homicide trials

Once participants are identified, it may require multiple attempts and strategies to make contact, engage and receive responses (e.g., letters, phone calls, email, home visits). Each strategy must be considered carefully due to possible safety concerns.

Conducting trauma-informed research and interviews

Participating in the research project must offer a reciprocal relationship where the researchers and the “research subjects” both gain from the experience. Research subjects should be given choice and voice about how they will participate in the project. Participants should be given choice about who they will be interviewed by, where the interview will take place, who they will seek support from if necessary, and have a voice in sharing their information with the broader community. Research subjects may seek or require the following when participating in the research study: adequate compensation, transportation, childcare, assurance of confidentiality, culturally appropriate support persons, counselling, interpretation services or conducting the interview in participant’s first language. We must make the results of the research accessible and available to the participants. Information about the research study, process, consent, and how results will be disseminated must be presented in accessible formats. It must be made clear to research subjects that they are free to withdraw consent to participate at any time.

Helpful strategies for minimizing stress when conducting interviews include:

- offering choices for how, when, where and with whom the interview will be conducted

- providing interview questions in advance for review and preparation

- meeting interviewer in advance – so not telling personal details to a stranger

- offering multiple breaks during an interview session

- conduct interviews in the form of a conversation – allow for as much open-ended discussion and storytelling as possible

- ensure survivors have access to appropriate counselling (existing counsellor on standby or referral from interviewer)

Interviewers must receive training on interpersonal violence, cultural sensitivity, crisis intervention, safety planning, community resources prior to conducting interviews. Interviewers must be aware of the cultural background of those to be interviewed in advance of meeting them. Awareness of sensitivities related to honor and shame, cultural norms, and Indigenous history will assist in providing sensitivity during the interview process. Table 1 identifies some things that research participants may be seeking, or need, to be involved in the research study, and how the interviewer can meet those needs. Interviewers should conduct a number of practice or mock interviews with other team members before interviewing research participants.

Table 1. How Interviewers Can Meet the Needs of Research Subjects

|

Choice and Voice: What people being interviewed may want or need to participate in a research study |

What interviewers need to know or have |

|---|---|

| Choice about when, where, how they will participate; who they will speak with | Be trauma-informed – support and respond to choices and needs of person being interviewed |

| A chance to tell their story at their own pace in their own language |

Empathy, warmth, awareness of trauma reactions, active listening skills. Offer breaks, flexibility in interview schedule |

| An interpreter with expertise in field of domestic violence | Awareness of potential language and interpretation needs of those being interviewed |

|

To know that their contribution matters, will have an impact on preventing tragedies in similar circumstances in the future; to understand the purpose and intended outcome of the study; that they can revoke consent at any time |

Understanding of purpose of research and ability to convey this in plain language; clarify ongoing consent |

| Respect, to be believed, acknowledgement | Open mind, non-judgmental |

| Assurances of confidentiality | Ability to maintain confidentiality |

|

Follow-up and referral to culturally appropriate support services |

Culturally specific sensitivity training, awareness of help sources, referrals |

| A support person at the interview or available directly after the interview |

Be aware of potential trauma responses and how to respond appropriately Ensure that supports are available if required |

Strategies for mitigating potential vicarious trauma of research team members

It was noted that it is not possible to prevent vicarious trauma among research team members, but the trauma may be mitigated through self-care and trauma-informed approaches. These strategies must be provided in the context of comprehensive training on vicarious trauma and the interview process, and ongoing supervision. Not every person is suited to this type of work, and those conducting interviews should be screened and carefully selected. Personal trauma histories may have a positive or negative impact on this work.

Figure 4. Strategies for Mitigating Vicarious Trauma

Knowledge mobilization activities

The CDHPIVP has developed a comprehensive knowledge mobilization plan which includes quarterly newsletters, homicide briefs, comprehensive literature review, peer-reviewed and grey literature publications, webinars, and website (www.cdhpi.ca). The Partnership meeting

was followed by a 2- day conference which included 4 plenaries, 59 workshops, poster session, and 435 registrants. To date, 10 annotated bibliographies, 3 homicide briefs, 1 fact sheet and 5 newsletters have been published and distributed.

Meeting attendees provided input on how to enhance the existing knowledge mobilization plan and activities. Suggestions included expanding knowledge products beyond written materials. People are reading less or have less time to read everything that is created.

Suggestions included presenting research findings to partner organizations; more use of webinars, TedTalks, podcasts, sound bites and videos. Suggestions to improve reach included ensuring the website is user-friendly and accessible; providing resources in multiple languages, reaching out to remote communities via personal connections. Use of social media was encouraged, however it is important to understand who the audience is and tailor messaging accordingly.

Partnership Evaluation

Meeting attendees provided input on how to keep partners and collaborators engaged with the project. It was recommended that we determine what each partner’s needs, goals and/or desired level of engagement are to determine how to meet these needs. We need to determine where partners’ strengths and interests lie and match these to the skills sets required for various activities within the project. Questions to consider for role clarification include:

- What can I do to contribute to the project? Can I do more?

- What will be the value added? For the project? For the partners?

- When is input needed?

The CDHPIVP needs to keep partners informed of project results (via email and social media) and provide shareable information to partners. Partners would like to receive more information on the outcomes, and the impact that the project is having as it progresses.

It was suggested that in-person meetings be held more frequently to keep partners apprised of activities, results and foster further collaboration and engagement in the project. Instead of conference calls, consider face-to-face meetings using technology such as Zoom. To further project engagement, we should include partners in event planning and coordination. Additionally, the CDHPIVP should consider putting the names and/or logos of all partners on all knowledge products disseminated by the project.

Who else should we be engaging?

Organizations and groups were identified as potential partners that would improve representation across population groups and geographic regions for the CDHPIVP. To improve collaboration and representation from immigrant and refugee populations, organizations such as the Canadian Muslim Women’s Association and Regina Open Door Society were suggested. Other groups include ethnic community centres, cultural groups, and settlement service organizations. The project would also benefit from enhanced representation from the justice sector including more police agencies, family and domestic violence courts, domestic violence coordinating committees, family mediators, victim service agencies, corrections and probation services (e.g, John Howard Society, Elizabeth Frye Society), and batterer intervention programs. To enhance participation from Indigenous organizations, the CDHPIVP may consider reaching out to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women Inquiry, elders and band councils. Additionally, the CDHPIVP should consider reaching out to child protection agencies and health sector agencies such as hospital-based domestic violence/sexual assault treatment centres, mental health agencies, and addictions services.

Meeting participants completed a modified version of the Community Impacts of Research Oriented Partnerships (CIROP) survey. We received more than 50 completed surveys. Some people chose not to complete the survey as this meeting was their first substantial engagement with the project. Some people were new agency representatives, and were less aware of the project activities so felt unable to report meaningfully about the impact of the partnership on themselves individually or on behalf of the organization they represented. Survey results included the following:

- 71% reported that they shared CDHPIVP resources or information with their organization, community or networks.

- The CDHPIVP has increased or changed personal knowledge or understanding about a topic for nearly ¾ of respondents.

- Almost ¾ of respondents reported that the CDHPIVP confirmed their feelings about the importance of particular issues.

- 1/3 reported that the CDHPIVP has improved their ability to find or access relevant information.

- The CDHPIVP has changed belief/understanding about the importance of domestic homicide risk assessment, risk management and safety planning for 2/3 of respondents.

- More than 60% of respondents indicated that involvement in the CDHPIVP has provided them with an opportunity for professional or personal development.

- About 1/3 reported that involvement with the CDHPIVP increased or changed their organization’s knowledge or understanding about a topic.

- 70% agreed that involvement with the CDHPIVP improved their personal access to up-to-date information, and about ½ of respondents agreed that involvement with the CDHPIVP improved their organization’s access to up-to-date information.

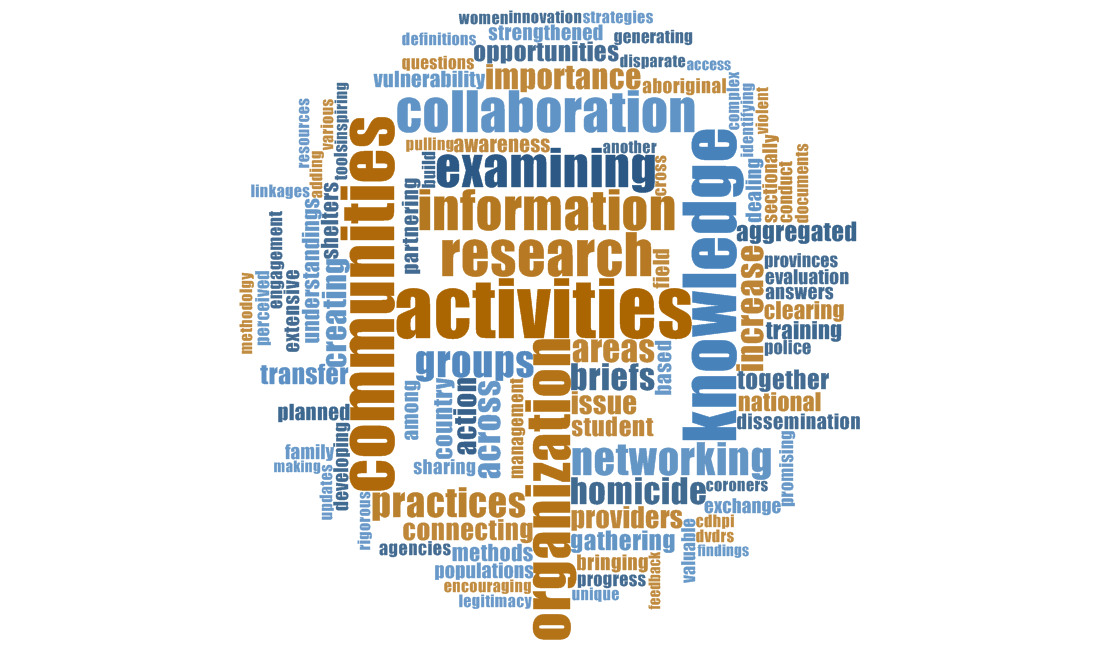

Participants were asked to identify the partnership’s major areas of impact. Responses were analyzed using NVIVO and a word frequency was conducted. The following Word Cloud provides a visual representation of responses.

Areas where the CDHPIVP has had less impact in the first two years of the grant include:

- Clearly delineating roles for partners and collaborators

- Enhancing opportunities for collaboration and connection among partners

- Stimulating changes in government policies and funding

- Dissemination in peer-reviewed journals

- Knowledge mobilization that is beneficial to community partners in their own work

- Planning for the possibility of long-term change in domestic violence service practices.

These results indicate that the CDHPIVP has work to do to improve the experiences of partners, collaborators and students involved with the project. Experiences of benefit vary depending on the person’s level of engagement and length of time linked to the project. The CIROP will be administered again at the end of the project.

Appendix A: CDHPIVP Partnership Members

Co-Investigators

Diane Crocker, Saint Mary’s University

Myriam Dube, Université du Québec à Montréal

Mary Hampton, University of Regina

Nicole Letourneau, University of Calgary

Kate Rossiter, Simon Fraser University

Jane Ursel, University of Manitoba

Collaborators1

Joanne Baker, BC Society of Transition Houses

Linda Baker, Western University

Mohammed Baobaid, Muslim Resource Centre for Social Support and Integration

Janelle Braun, Manitoba Justice Victim Services

Julie Czeck, Provincial Office of Domestic Violence, British Columbia

Deborah Doherty, Public Legal Education and Information Service of New Brunswick

Jo-Anne Dusel, Provincial Association of Transition Houses and Services of Saskatchewan

Anuradha Dugal, Canadian Women’s Foundation

Claudette Dumont-Smith, Consultant

Jordan Fairbairn, Consultant

Crystal Giesbrecht, Provincial Association of Transition Houses and Services of Saskatchewan

Carolyn Goard, Alberta Council of Women’s Shelters

Sepali Guruge, Ryerson University

N. Zoe Hilton, Waypoint Centre for Mental Health Care

Catherine Holtmann, Muriel McQueen Fergusson Centre for Family Violence Research

Margaret Jackson, FREDA Centre for Research on Violence Against Women and Children

Randy Kropp, Forensic Psychiatric Services Commission, British Columbia

Geneviève Lessard, Laval University

Maggie MacKillop, Homefront Calgary

Barb MacQuarrie, Western University

Lise Martin, Women’s Shelters Canada

Cathy Menard, Northwest Territories Office of the Chief Coroner

Pertice Moffitt, Aurora Research Institute

David O’Brien, Government of Prince Edward Island

Aruna Papp, Consultant

Tracy Porteous, Ending Violence Association of BC

Clark Russell, Provincial Office of Domestic Violence, British Columbia

Katreena L. Scott, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education

Deborah Sinclair, Consultant

Verona Singer, Consultant

Rona Smith, Government of Prince Edward Island

Catherine Talbott, Provincial Office of Domestic Violence, British Columbia

Wendy Verhoek-Oftedahl, Government of Prince Edward Island

Lana Wells, University of Calgary

Lorraine Whalley, Fredericton Sexual Assault Crisis Centre

Partner Organization Representatives2

Alberta Council of Women’s Shelters -Carolyn Goard

Alberta Human Services

Awo Taan Healing Lodge -Josie Nepinak

BC Forensic Psychiatric Services Commission – Randy Kropp

BC Office of the Representative for Children & Youth

BC Society of Transition Houses - Joanne Baker, Amy FitzGerald

Canadian Network of Women’s Shelters and Transition Houses – Krystle Maki

Canadian Women’s Foundation

Centre de recherche interdisciplinaire sur la violence familiale et la violence faite aux femmes - Pamela Alvarez-Lizotte

Centre for Research & Education on Violence against Women & Children – Linda Baker, Barbara MacQuarrie

Child and Family Services, Prince Edward Island -Wendy Verhoek-Oftedahl

Circling Buffalo – Sharon Mason, Patricia Dorion

Ending Violence Association of BC – Tracy Porteous

FREDA Centre for Research on Violence against Women and Children – Margaret Jackson

Fredericton Sexual Assault Crisis Centre – Lorraine Whalley

Halifax Regional Police – Scott MacDonald

HomeFront – Liz Driessen

Ma Mawi Wi Chi Itata – Diane Redsky

Manitoba Domestic Violence Death Review Committee – Crystal Gartside

Muriel McQueen Fergusson Centre for Family Violence Research – Jael Duarte

Muslim Resource Centre for Social Support and Integration – Mohammed Baobaid

National Aboriginal Circle Against Family Violence – Carole Brazeau, Anita Olsen Harper

Native Women’s Association of Canada

Office of the Chief Coroner - NWT – Cathy Menard

Office of the Chief Coroner - Ontario Domestic Violence Death Review Committee – Carol Ritchie

Provincial Association of Transition Houses and Shelters of Saskatchewan – Jo-Anne Dusel, Crystal Giesbrecht

Provincial Office of Domestic Violence, BC

RESOLVE Alberta – Nicole Letourneau

Saint Marys University – Diane Crocker

University of Calgary, Faculty of Social Work

University of Guelph – Myrna Dawson

University of Manitoba – Jane Ursel

University of Regina – Mary Hampton

University of Western Ontario

Invited Guests

Tammy Bobyk, Ontario Native Women’s Association

Jacquelyn Campbell, Johns Hopkins School of Nursing

Busra Yalcinov, University of Guelph

Research Assistants and Students3

Abir Al Jamal, Muslim Resource Centre for Social Support and Integration

Danielle Bader, University of Guelph

Jennifer Bon Bernard, University of Calgary

Keri Cheechoo, University of Ottawa

Randal David, Western University

Meghan Gosse, Dalhousie University

Anna Johnson, University of Guelph

Nicole Jeffrey, University of Guelph

Marlee Jordan, Saint Marys University

Natasha Lagarde, Native Women’s Association of Canada

Salima Massoui, Université du Québec à Montréal

Laura Olszowy, University of Western Ontario

Mariana Paludi, Saint Marys University

Camille Pare-Roy, Université du Québec à Montréal

Olivia Peters, University of Manitoba

Julie Poon, University of Guelph

Katherine (Kay) Reif, Western University

Dylan Reynolds, University of Guelph

Gursharan Sandhu, University of Guelph

Gurneet Saini, University of Guelph

Mike Saxton, University of Western Ontario

Danielle Sutton, University of Guelph

Melissa Wuerch, University of Regina

Sarah Yercich, Simon Fraser University

Management Team

Marcie Campbell, University of Western Ontario

Myrna Dawson, University of Guelph

Peter Jaffe, University of Western Ontario

Anna-Lee Straatman, University of Western Ontario

1 This is a list of all collaborators. Not all were in attendance at the meeting.

2 All partner organizations are listed and the representative who attended the meeting where applicable. Collaborators may also be partner organization representatives.

3 Reflects students and research assistants who have contributed to the project since its inception. Not all attended meeting.

View Printable PDF Version

View Printable PDF Version